Previously: At Jacksonville, Johnnie Smith freighted from Crescent City, on the coast near the California line, to Jacksonville. In 1853 the Rogue River war broke out and many settlers and Indians were killed.

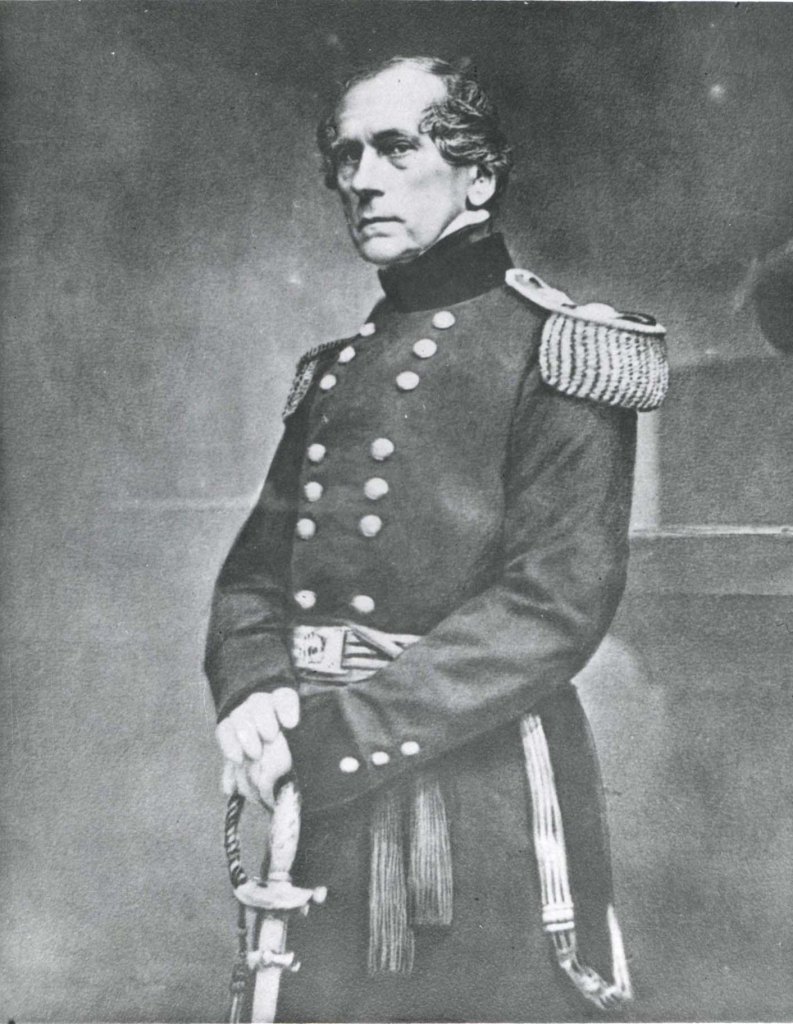

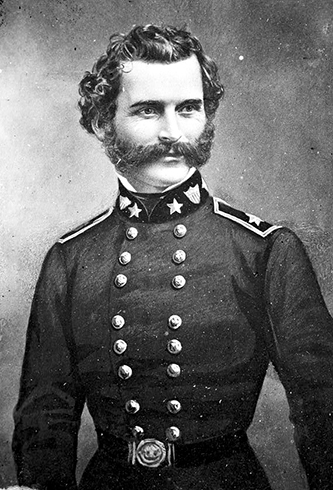

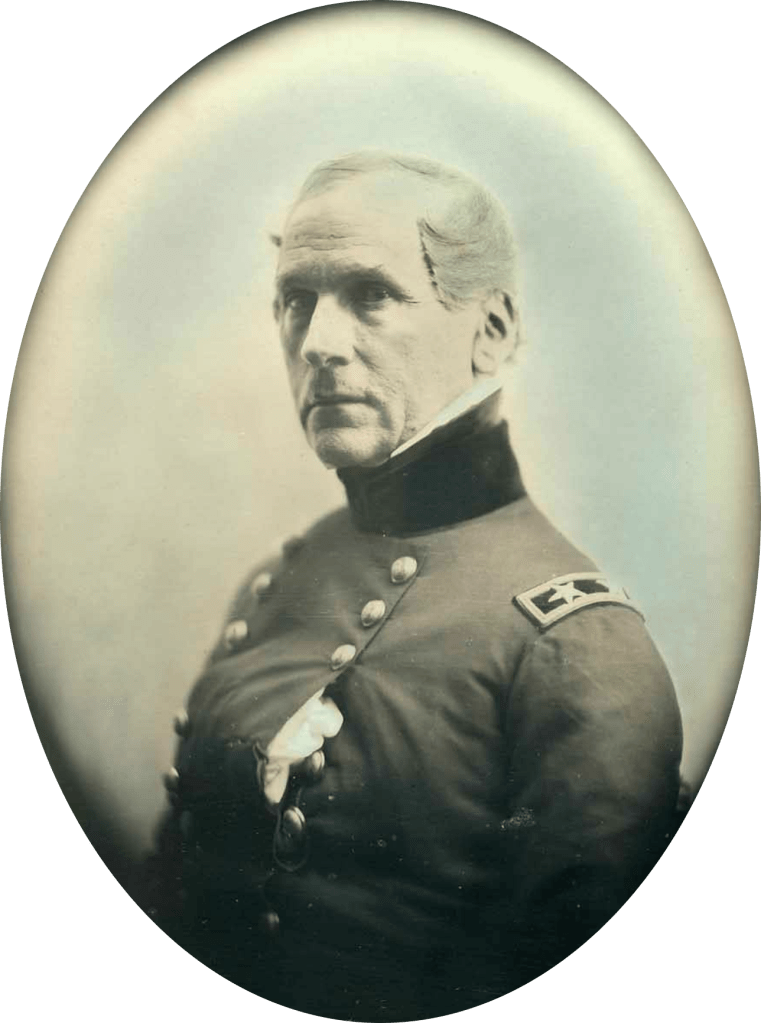

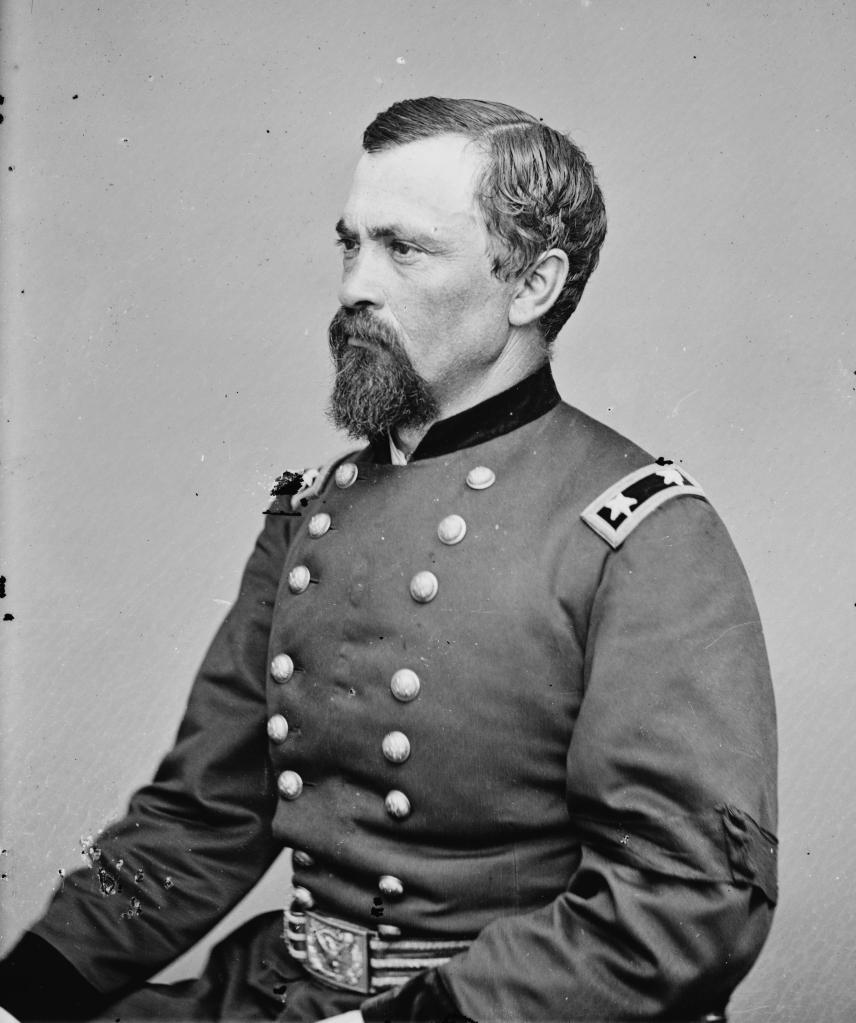

Major General John E. Wool, commanding the District of the Pacific:

March 31st, 1854

The difficulty of preserving the peace of the country is daily increasing, owing to the increase of emigrants, who are constantly encroaching upon the Indians and depriving them of their improvements. This produces collisions between the two races, white and red, which too frequently end in bloodshed. To keep them quiet and to preserve peace, a large military force is indispensable.

We have now less than one thousand men to guard and defend California, Oregon, Washington and Utah – altogether in size an empire of itself. A larger military force is indispensable.

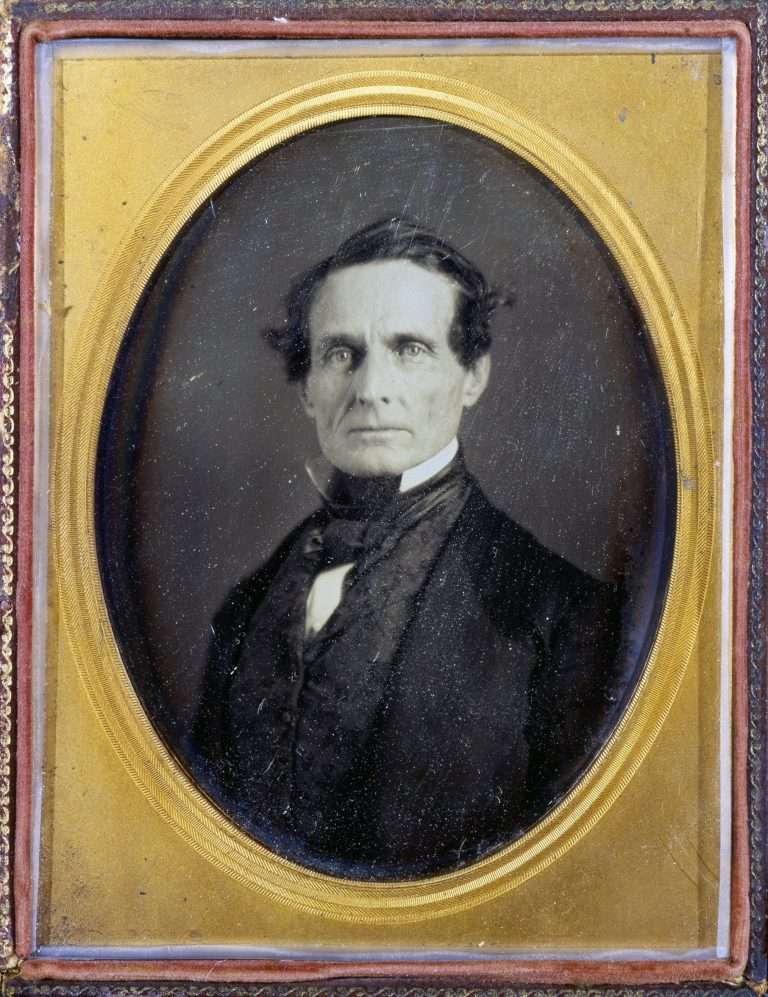

Jefferson Davis, Secretary of War:

April 14th, 1854, reply to Gen. Wool

Your knowledge of the numerical strength of the army, and the demand for troops upon the frontiers, could only in the contingency of an increase of the army by an act of Congress permit you to hope for a larger force. No such increase has yet been made.

General Wool:

May, 1854, reply to the Secretary of War:

In urging, in my communication of February 28th, that the troops be sent to California, my object was simply to apprise you, as well as the General-in-Chief, of the necessity of sending troops as soon as practicable, in order that the peace and quiet of the country might be preserved, which is almost daily threatened by the whites and Indians coming into contact with each other.

A. M. Rosborough, Indian Agent:

In June, 1854, I was informed by several chiefs of the Scott’s and Shasta valley tribes that runners had been sent to their tribes to summon them to a general war council, to be held at a point on the Klamath called Horse Creek.

I consulted with Lieutenant J. C. Bonnycastle, United States army, then stationed at Fort Jones.

He and myself concurred in the propriety of advising the chiefs who had reported the movement to attend the war council and report to us the whole proceedings.

The chiefs returned from the council and reported the tribes of Illinois River, Rogue River and the upper Klamath River, and their tribes represented in the council, and all but themselves [the chiefs that had reported the movement to me] were for combining and commencing in concert an indiscriminate slaughter of the whites.

They reported that they were first importuned to join in the attack, and when they refused again and again, they were threatened by the other tribes with extermination; upon which they withdrew and the council broke up in a row.

C. S. Drew, Quartermaster General, of Oregon, dispatch to John W. Davis, Governor of Oregon:

July 7th, 1854

The recent Indian difficulty in Siskiyou county, California, resulted in the death of several Indians belonging to the different tribes of the northern section of California and to southern Oregon, two of whom are supposed to have belonged to the Modocs, located in the vicinity of Goose and Klamath lakes, directly on the immigrant road to this valley.

The Applegate, Klamath, Shasta, and Scott valley tribes have left their usual haunts and gone into the mountains in the direction of the Modoc country, with the avowed determination of joining with the several tribes in that vicinity for the purpose of getting redress for real or imaginary wrongs from any or all citizens who may fall within their grasp. …

No preparations are being made by traders, either of this or the adjoining counties of California, for an adventure on the plains this season, as has usually been the custom; consequently much suffering among the poorer class of immigrants must inevitably be the result.

A small detachment of dragoons will probably be dispatched from Fort Lane, and will no doubt render all the assistance in their power to the immigration at large; but the entire force stationed at that post being small, numbering scarcely seventy men, it cannot be expected that more than thirty can he dispatched on this service.

This number, you will readily perceive, is insufficient to perform the service necessary to be rendered in emergencies of this kind.

The present financial condition of the citizens of this section of the Territory renders it impossible to raise the means for the relief of such as may stand in need, owing to the fact that none have recovered from the disastrous consequences of the late war. Supplies could not be procured here sufficient to provision thirty men as many days without the probability of an immediate remuneration therefor. The merchants here are, many of them, paying five per cent, a month for money, with which they furnished supplies for the volunteer service in the late Rogue river war, while others have been compelled to relinquish their former avocations altogether, not being able to effect loans even at the above ruinous rates of usury.

In view of these facts, I most respectfully beg leave to inquire whether it is in your power to render any aid whatever in this emergency? …

The State of California has authorized the raising of a company of mounted rangers in the adjoining county of Klamath (the officers of which have already been duly commissioned) for the sole purpose of affording ample protection to her citizens from the incursions of hostile Indians.

If such an act is necessary there, where there are comparatively few Indians, and those mostly ignorant of the use of firearms, it must be doubly so here, where there is probably three times the number of Indians, well armed with fire-arms of the best quality, and who have been taught by experience the most effectual mode of warfare.

I could cite other precedents, but fearing that I have already overtaxed your patience, I subscribe myself your obedient servant,

C. S. DREW,

Quartermaster General of Militia

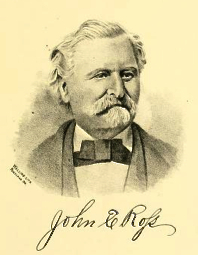

Governer John W. Davis to Colonel John E. Ross, Ninth Regiment Oregon Militia:

July 17, 1854

Sir: Information has reached this department from various sources, that there is an unusual degree of excitement among the several tribes of Indians on the southern route of the immigration from the Atlantic States to this Territory, and that there is much reason to fear that a concerted plan of operation has been formed by these tribes for the purpose of plundering and perhaps murdering our fellow-citizens on their way to Oregon.

Under these circumstances, I have to suggest to you the propriety of calling into the service of the Territory a small force of mounted volunteers, for the purpose of meeting and escorting the immigration through the hostile country. The number of men should not, in my opinion, exceed seventy or eighty, and they should be chosen from among those who are best acquainted with the country and the habits of the Indians.

I am aware of the many embarrassments under which you will labor if it should be considered necessary to raise such a command without a single dollar to defray expenses; you will be compelled to rely upon the liberality and patriotism of our fellow-citizens, who in turn will be compelled to rely upon the justness of the General Government for their compensation. As soon as the necessary force is raised, you will please report the fact to this department, together with the names of the officers who may be chosen to command the same.

For further information, I ask to refer you to my communication to Quartermaster General Drew of even date herewith, and remain,

Very respectfully, yours, JOHN W. DAVIS, Governor.

Col. John E. Ross to Cap. Jesse Walker:

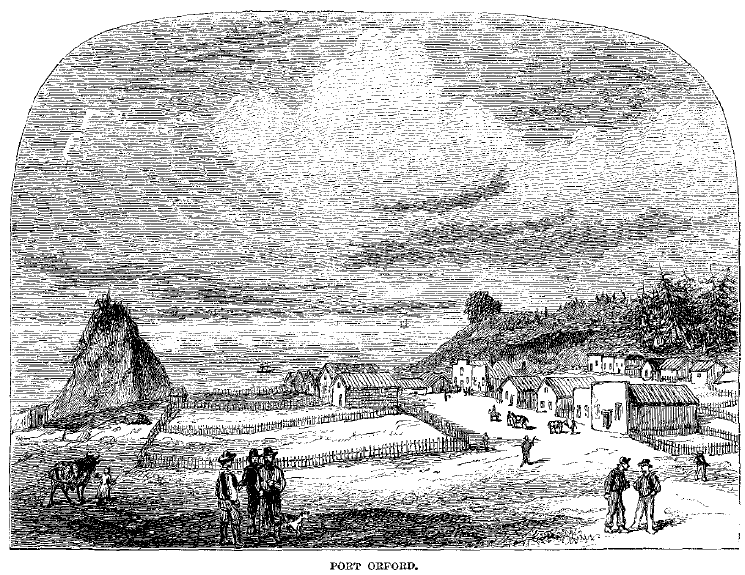

Jacksonville, O.T., August 8, 1854.

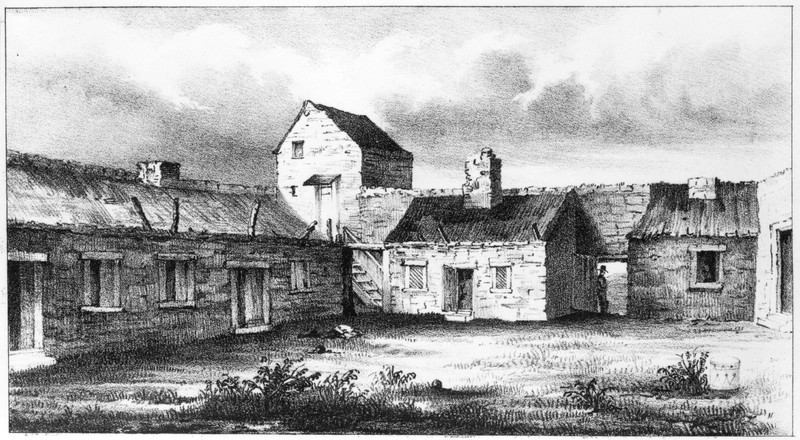

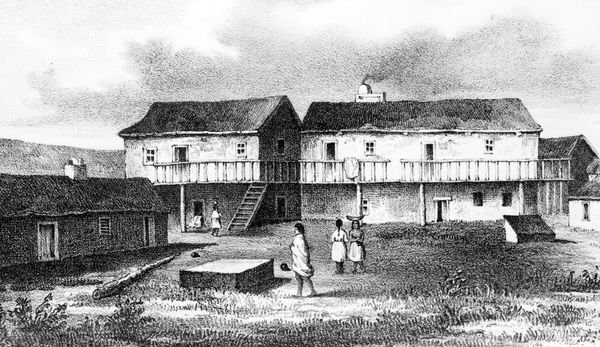

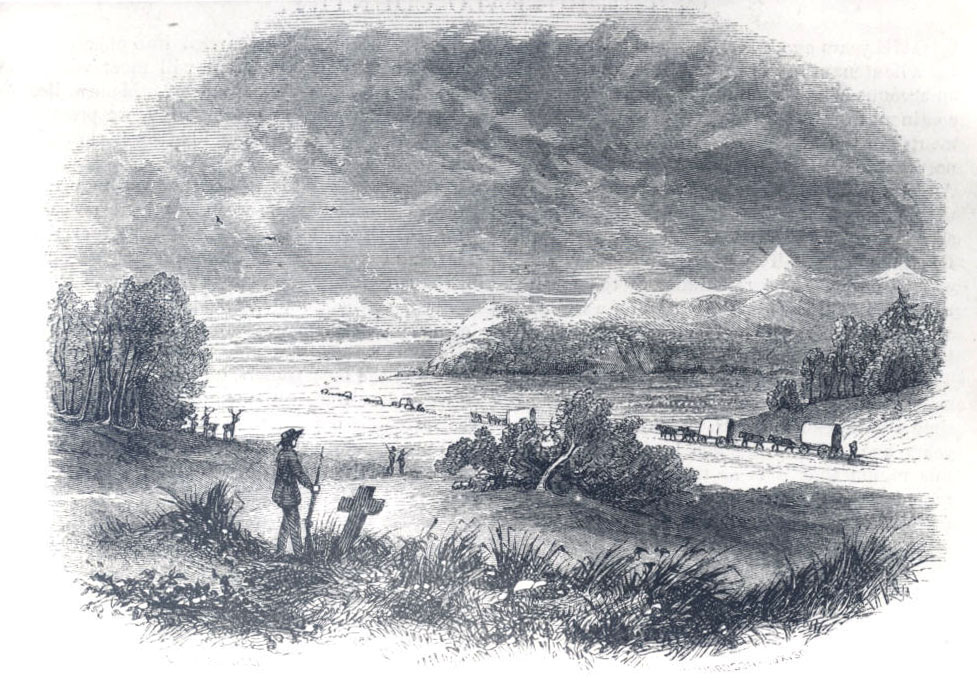

Sir: You will immediately proceed with your company, along the Southern Oregon immigrant trail, to some suitable point near Clear Lake or on Lost River, in the vicinity of the place where the immigration of 1852 was massacred by the Indians, where you will establish your headquarters. From this encampment you will send out detachments of such numbers as you may deem effective as far as the Humboldt River, giving them instructions to collect the immigrants together in as large companies as convenient, the better to withstand the attacks of the Indians. Each train will be strictly guarded through the entire hostile country.

It is to be hoped that your company, in the heart of their country, will deter the Indians from committing their annual depredations upon the immigrants coming in by this route. Your treatment of the Indians must in a great measure be left to your own judgment and discretion. If possible, however, cultivate their friendship, but if necessary for the safety of the lives and property of the immigration, whip and drive them from the road.

JOHN E. ROSS,

Col. Commanding, 9th Regiment, O.M.

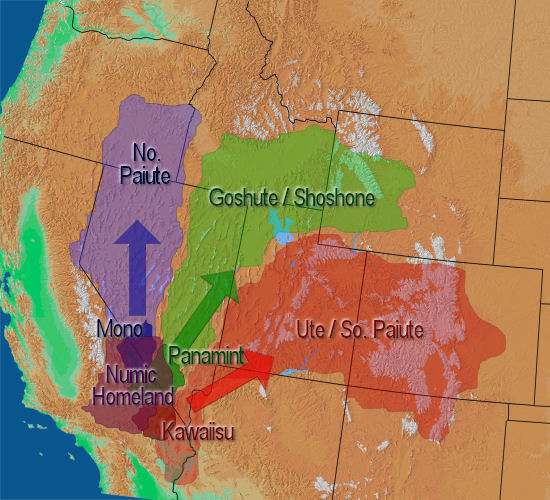

The Snake Indians on the northern Oregon emigrant road and their allies the Modocs, Piutes and a portion of the Shasta Indians, who reside on the Southern Oregon Emigrant Road, have ever been very hostile against the whites, and the deadly hostilities of these Indians were particularly manifested in the early part of the summer of 1854 by a large body of them collecting together on the southern trail near Tule Lake…

…and by their stealing stock from the settlements in Southern Oregon, and taking a pack train, and killing two men on the Siskiyou Mountains, on the main road from Oregon to California; and soon afterwards by the indiscriminate massacre of men, women and children of a whole emigrant train on the northern Oregon emigrant road near Fort Boise.

The 6-wagon train Ward Party was a typical group of emigrants passing through the Boise Valley on the Oregon Trail in 1854. The Party consisted of about 20 members, and on August 20, 1854, the group was traveling along the southern bank of the Boise River. Like other emigrants on this stretch of the Oregon Trail, the Ward Party’s immediate destination was Fort Boise.

About 20 miles from the Fort, the Ward Party took a short noon break to eat and rest. The Wards pulled their wagons off the Trail for lunch and to water their stock when two White Men and three Native Americans approached the Party to trade for a horse. When the trade failed, one of the Indians attempted to ride off with the horse and was killed.

Being on the Oregon Trail, having a horse stolen was a very grave circumstance, and a white man shot the thief down, initiating the slaughter.

Fearing retribution, the Wards hurried back to the Trail and corralled their wagons to defend themselves from about 60-Indians, who had raced from their encampment across the river to give battle. For nearly 2-hours, 6-men defended the wagons. When the last defender fell, the wagons were rushed and 2-boys and 2-non-combatant men were killed. The women and children were gathered in a wagon and driven toward the river.

Soon after, the entire Party was ambushed by Snake and Shoshone Native Americans. The Wagon Train Leader, William Ward, fell mortally wounded in the first few minutes, and with careful speed and defence tactics, the men of the Ward Party reached out to protect the women and children and hold off the ambushers. Their defense turned out to be quite futile, as most were killed before sundown while the women were sexually tortured and killed.

Children were held over a large, blazing fire and were burned to death. 13-year-old Newton Ward was shot with an arrow and left for dead; his 15-year-old brother William Ward was shot with an arrow through his lung. By feigning death, the brothers would ultimately survive the attack. William crawled for several days with the arrow still protruding through his chest until he reached Fort Hall. They were the only two who survived the attack. …

The attack did not go unnoticed. Seven men from the Yantis Party heard gunfire and women’s screams and hurried to the rescue. They were forced to retreat when one of their own men was killed. That evening, they returned, finding dead and dying from both sides. Injured 13-year old Newton Ward, was carried back to the rebuilt Fort Boise Trading Post (near present-day Parma). In all, 19-immigrants were killed, but both Newton Ward and William Ward survived. The number of Native American dead from the battle was never tallied.

Two days after the attack, a rescue party from Fort Boise found the 4-burned wagons and the bodies of the Ward Party men. The body of 18-year old Mary Ward was found in a draw by a burned wagon. 30-year old Mrs. White’s battered body was found in a Pond by the Boise River. The mutilated bodies of 37-year old Mrs. Margaret Ward and three young Children were located across the River in the abandoned Indian encampment. Two younger children could not be located but William Ward, with an arrow in his side, later walked into Fort Boise.

To suppress these hostilities, in August, 1854, seventy-one men, rank and file, of the 9th Regiment of Oregon Militia, under the command of Captain Jesse Walker, were called into active service by Colonel John E. Ross, under orders from John W. Davis, then Governor of Oregon Territory, for the protection of the emigrants on the Southern Oregon emigrant trail…

Captain Walker’s company traveled the trail from Jacksonville to the Humboldt River, and up the Humboldt about sixty miles, making a distance of five or six hundred miles, and met the enemy several times in large numbers, whipped, dispersed and drove them from the trail, and returned to Jacksonville.

Owing to the hostilities of the Indians no traders were stationed during the fall along the trail, and many of the emigrants were entirely destitute of bread. Detachments of Captain Walker’s command accompanied every train through the hostile country, and they frequently furnished the indigent emigrants with the necessaries of life.

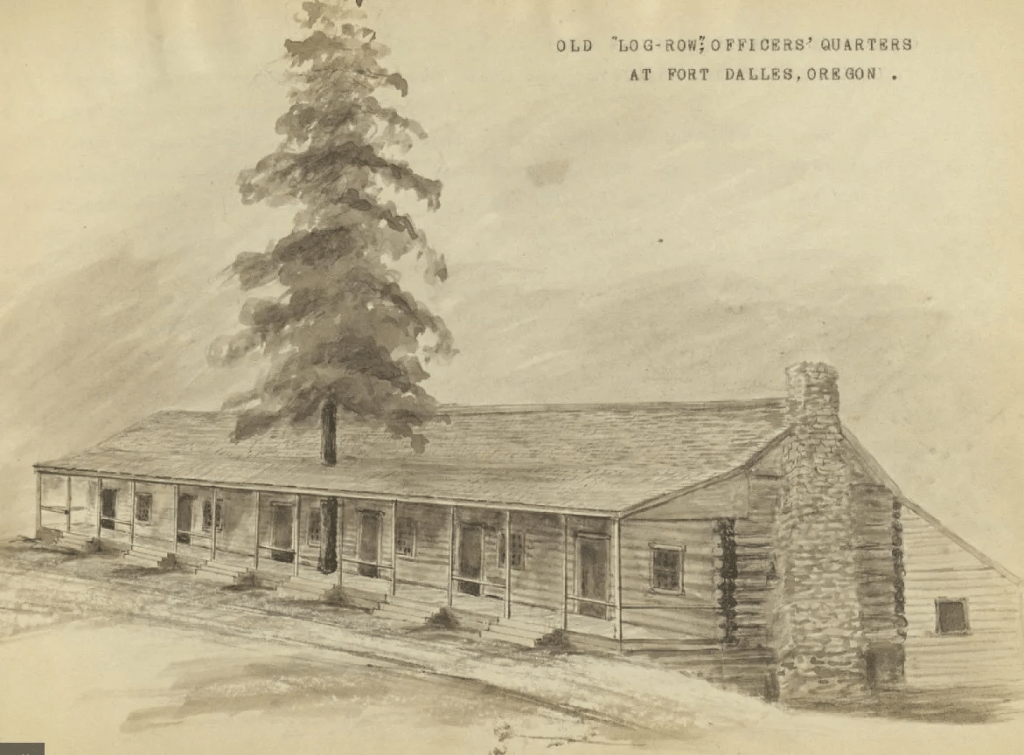

Captain Olney’s company traveled the road from Fort Dalles to beyond Fort Boise, a distance of about five hundred miles, and returned to the Dalles with the last of the emigration.

The regular army in the vicinity was wholly unable to keep peace in the settlements, and both companies were actually necessary for the protection of American citizens.

They did good service by feeding the destitute, and saving the lives and property of our best citizens from the ravages of hostile and bloodthirsty savages.

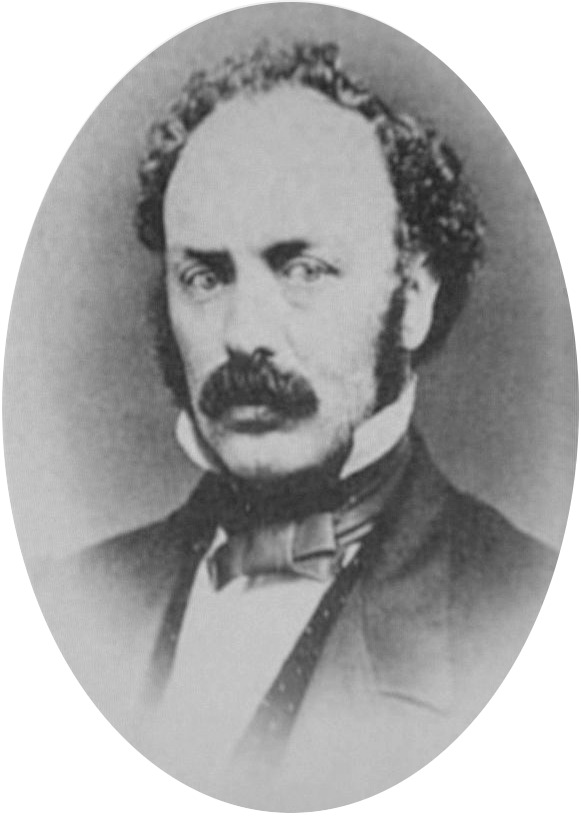

John E. Smith:

In 1854, I joined a company of the Oregon Volunteer Militia made up at Jacksonville. The company was used as an escort to go out on the plains and meet settlers coming to Oregon by the Southern route.

I worked in the Quartermaster’s Department and had charge of the freight outfit under Captain Jesse Walker. We did everything then with pack animals. I have my discharge papers yet. I had served in the Rogue River Indian War of 1853-55.

A volunteer militia company from Jacksonville was organized in the summer of 1854, under the command of Captain John E. Ross, to patrol the Southern Oregon Emigrant Road. As a packer for Captain Jesse Walker’s “Pacific Rangers”, Smith was supplying a 75-man force across hundreds of miles of high-desert wilderness.

By late 1854, acting Oregon Governor George Law Curry realized the federal government wasn’t ready to help with troops or funds for militias. He authorized the expeditions anyway, gambling that if the volunteers successfully protected the emigrants or fought a major battle, the political pressure on Washington D.C. would be so great that Congress would be forced to pay. The expeditions were essentially “buy now, pay later” operations, fueled by local credit and political defiance against the federal government.

The Oregon Territorial Government issued vouchers and scrip to pay the volunteers, which was only worth something if the U.S. Congress eventually decided to reimburse the Territory. Because of this, “War Scrip” often traded at 40 to 60 cents on the dollar in Jacksonville saloons and stores.

This inevitably created a speculation bubble around the conflict. Merchants charged the militia 300% markups because they knew it might take years to get paid, if they got paid at all. This also meant that, since the Territory couldn’t offer the security of federal pay, they offered inflated wages to attract experts who could keep Walker’s men from starving in the desert.

Oregon Statesman:

August 5, 1854

The expedition under Capt. Walker moved out on the 2nd inst. Much credit is due to Col. Ross and the local committee for the dispatch with which the company was equipped. The baggage train is of the first order, consisting of animals well-accustomed to the rigors of the trail. With such a foundation, the rangers may move with confidence against the marauders of the Modoc country.

Joel Palmer, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs of Oregon, September 11, 1854:

It would appear absolutely necessary to detail a company of mounted men each year to scour the country between Grand Ronde and Fort Hall during the transit of the emigration.

Official information has been received that an emigrant train has been cut off this season by these savages; eight men have been murdered, and four women, and a number of children taken captive, to endure suffering and linger out an existence more terrible than death. Of this party a lad, wounded and left for dead by the Indians, alone survives. Other trains may meet a similar fate, and none left to tell the tale.

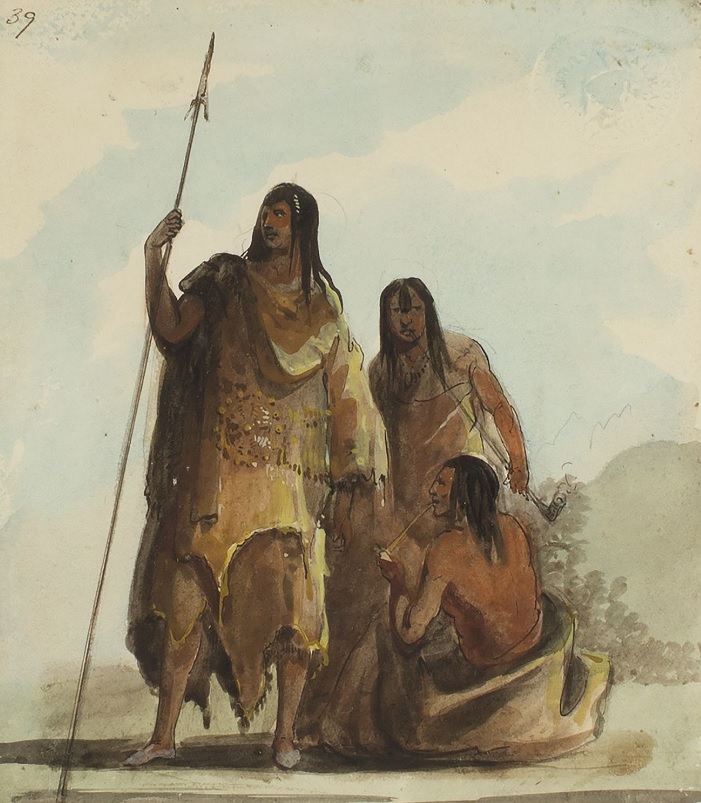

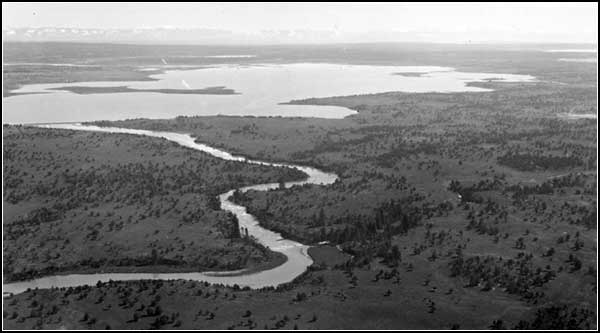

East of the Cascade Mountains, and south of the 44th parallel, is a country not attached particularly to any agency. That portion of the eastern base of this range extending twenty-five or thirty miles east, and south to the California line, is the country of the Klamath Indians.

East of this tribe, along our southern boundary, and extending some distance into California, is a tribe known as the Modocs. They speak the same language as the Klamaths. East of these again, but extending farther south, are the Moetwas. These two last-named tribes have always evinced a deadly hatred to the whites, and have probably committed more outrages than any other interior tribe. The Modocs boast, the Klamaths told me, of having, within the last four years, murdered thirty-six whites.

East of these tribes, and extending to our eastern limits, are the Shoshones, Snakes or Diggers. Little is known of their numbers or history. They are cowardly, but often attack weaker parties, and never fail to avail themselves of a favorable opportunity for plunder.

General Wool, September 14th, 1854:

In reply to a communication to Captain A. J. Smith, first dragoons, commanding Fort Lane, in which I called his attention to apprehended difficulties with the immigrants and the Indians, near Goose Lake, he informs me that all necessary measures have been taken in that quarter, and that he is on the alert to prevent disturbances.

It seems a company of volunteers has been mustered into service, by the authority of the Governor of Oregon.

Reports from Major G. J. Rains, 4th Infantry, commanding Fort Dalles, O.T. informed me that on August 20th the emigrants en route for the west were attacked on Boise River, a branch of the Snake River, and eight men killed, and four women and five children carried away captive with all their property.

Assistance was asked for by the Indian Agent (Mr. R. R. Thompson) and others, and I (Major Rains) dispatched Brevet Major Haller, Lieutenant Macfeely and Assistant Surgeon Suckly, with 26 soldiers, to the scene of the difficulty.

Major Haller left August 30, and since, a company of volunteers having offered, 30 strong, their services were accepted and they were furnished with arms, horses, ammunition and rations, and left here [Fort Dalles] yesterday, August 31st.

I came over the plains the second time in the summer of 1854, and came to Yreka, California, by way of the southern Oregon and northern California emigrant route, passing through the country of the Pi-ute, Modoc, and Klamath lake tribes of Indians. I emigrated that year, with my family, from Winchester, Iowa, and came to this place as a captain or foreman of a small train consisting of about fourteen persons, with about sixty head of stock.

We saw no indications of hostile Indians on our trip until we arrived in the vicinity of “Gravelly Ford,” on the Humboldt river. Just before arriving at this point large numbers of Indians began to show themselves, armed and painted, and exhibiting other signs of hostile intentions, such as the war dance, &c., always resorted to by them in time of war.

From the time we left Fort Hall it was our invariable custom to guard at night, and even with this precaution the Indians succeeded in stealing from me a fine American mare.

Shortly after the Indians had made their first hostile demonstrations, and after we had arrived at the Humboldt, two Indians were discovered by the guard crawling over the bank of the river where we had camped for the night, and were making directly towards our tents. The guard fired upon them, but unfortunately, it being dark, they made their escape, probably unhurt.

From the Humboldt river, across the Sierra Nevada mountains, to Goose lake, where it was our good fortune to meet the first detachment of Captain Jesse Walker’s company of Oregon mounted volunteers, under command of Lieutenant Westfeldt, we were in constant expectation of an Indian attack.

We saw an abundance of Indian “sign” every day, and it was evident that the Indians were collecting together along our route and making for “Bloody Point,” between Clear lake and Lost river, where, in 1852 and at other times, they had killed scores of emigrants and destroyed a large amount of property. Upon meeting Lieutenant Westfeldt, we were immediately furnished by that officer with an escort to Captain Walker’s headquarters, on Clear lake.

Here we staid over night, and next morning, with an escort of ten men, under Lieutenant Miller, we proceeded on our journey, passing “Bloody Point” unmolested, and arrived at Lost river just before dark.

Here, however, we soon discovered a large body of Indians across the river and immediately opposite our camp. Judging from the number we saw, and other indications, that they were too numerous for our small party to cope with successfully, in case of an attack, which it was evident they were preparing to make, Lieutenant Miller despatched a messenger to Captain Walker for a reinforcement which arrived at our camp some time before daylight next morning.

On the arrival of additional troops the Indians left the ground they had occupied during the night, and we were left to pursue our journey without further molestation. Our escort remained with us until our arrival at Klamath lake, where it left and returned, as we were then past all danger from Indians.

It was at Lost river that the party of thirteen men from Yreka, referred to in Captain Walker’s report, were attacked a few days before and compelled to retreat; and I have no hesitancy in saying that the timely arrival of Captain Walker and command in the hostile Indian country saved our property from destruction, and no doubt our lives.

In 1852, when the emigration was excessively large, and consequently much better able to protect itself against the Indians than was the emigration of 1854, very many were killed by the Pi-utes and Modocs along the same part of the route over which we were so fortunate as to receive armed protection.

In 1853 the emigration by this route was much less than that of the previous year; but it was amply protected by the order of General Lane, then commanding in the Rogue River Indian war, and consequently was saved any very material loss. A detachment of United States dragoons were also on duty in 1853, but no United States force was there in 1854.

It is also due to truth to say that many of the emigration of 1854 were wholly destitute of subsistence at the crossing of the Sierra Nevadas, nearly or quite three hundred miles from any settlement, and none had provisions that they could possibly spare. No traders were on the route to furnish the destitute with supplies; and had not aid in this particular been rendered by Captain Walker, much suffering from hunger, and in many instances starvation itself, must have been the result.

From a thorough knowledge of the Indian character, particularly of the region of country alluded to, I do not hesitate to affirm that an armed force is absolutely necessary for the protection of every emigration passing that way.

Captain Jesse Walker’s report to Colonel J. E. Ross:

Headquarters 9th Regiment O. M.,

Jacksonville, O. T., November 6, 1854.

Sir: Having been in active service with my company for upwards of three months on the southern Oregon immigrant trail, and being about to be discharged from the public service, I have the honor of submitting the following report of the expedition:

In pursuance to your orders of the 3d of August last I marched with my company from the head of Rogue River valley on the 8th of that month, and arrived at the crossing of Lost river on the 18th of the same month.

Soon after our arrival at this place we saw a party of 13 men from Yreka, California, returning, who had gone out to meet their friends that were expected to come this road from the States this season.

They informed me that they had just been fired upon by a large body of the Modoc Indians, of not less than 150 or 200 warriors, who had collected on both sides of the immigrant trail, on the north side of Tulé lake, at the sink of Lost River. Several shots had been fired on both sides, but the Yreka party, being so small, was compelled to flee and seek protection from my company, which they knew was close behind them.

As soon as I received this information I set out with sixty men for the purpose of making a charge upon the ranch. On arriving near to the Indian ranches we found it impossible to get our horses within 400 yards of the Indian encampment. We then immediately dismounted and took after them on foot, when they fled in great confusion to their boats and canoes (which lined the bank of the lake near the ranches) and rowed out on the lake far beyond the reach of our rifle balls, leaving behind them the whole of their camp equipage and provisions, which they had carefully collected and piled away in large quantities to subsist upon during the winter.

After a careful reconnoitre we found an Indian horse and two squaws in the tulés. After burning the ranches and provisions I released the squaws, upon their promising to use their influence to persuade the Indians to become friends to the whites.

From the 18th of August to the 4th of September we had several skirmishes with these Indians, killing several and taking a few prisoners; among the number was a half-breed Indian girl, about three years old. In all of these skirmishes the Indians would (when hard pushed by us) retreat to their boats, where it was impossible to follow them, although we made the attempt several times, wading in water up to our armpits. A few small boats were much needed for the company to attack the enemy successfully.

On the 4th of September the Indians, being entirely out of provisions, were compelled to beg for quarters, which were granted them upon their faithfully promising to be friendly and never to kill or rob another white person. These Indians have always been more hostile than any others on this road, but they seem now to desire to live on friendly terms with the whites, and by a small force being stationed in the vicinity of Goose lake I think they can be easily controlled.

Having made peace with the Modocs, and learning that the Pi-ute Indians were very hostile, and were stealing stock from immigrants in the vicinity of the Sierra Nevada mountains, on the 1st of October I moved my headquarters to Goose lake, and on the 3d of October took with me 16 men and proceeded along the immigrant trail to the east side of the Sierra Nevada, and there discovered a large Indian trail, running in a northeasterly direction.

I followed this trail about eight miles, when I came in sight of a large band of Indians encamped at the head of what I shall now call Hot Spring valley, which lies on the east side of these mountains. The Indians saw us crossing the mountains and immediately fled in all directions.

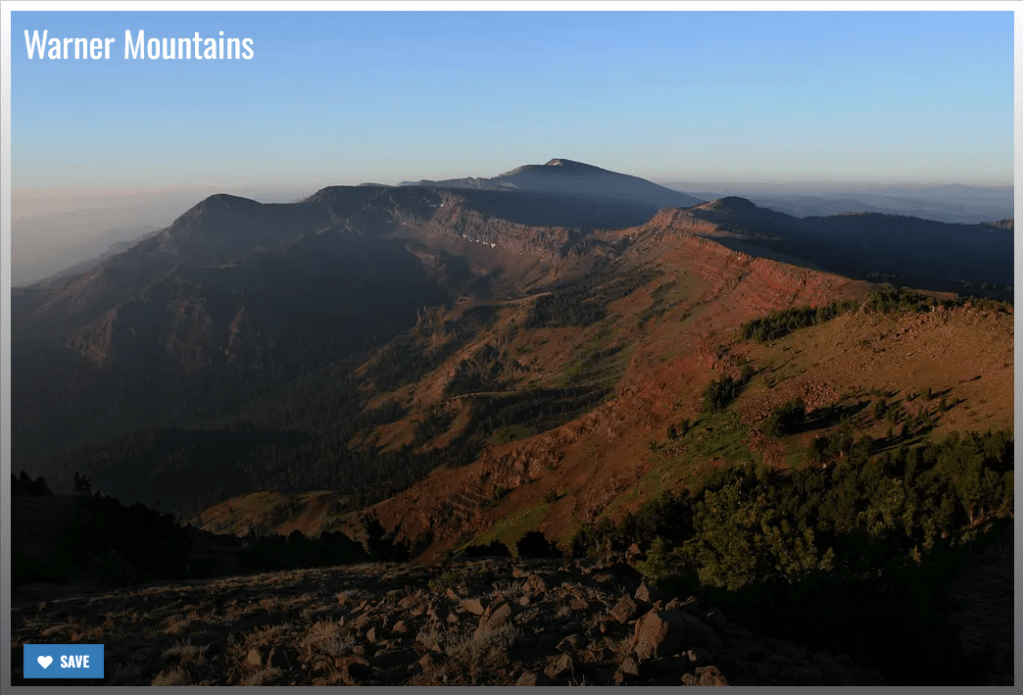

We pursued a large band of them north about forty miles, and on the second day came in eight of them, strongly fortified at the south end of Pi-ute valley. This fortification is a natural one, it being an immense rock of from thirty to one hundred feet in height. We named it Warner’s Rock, in honor of the late gallant Captain Warner, of the United States army, who was massacred, with three of his company, at or near this rock, by the Pi-ute Indians in 1849.

Today Pi-ute Valley is Warner Valley.

The rock somewhat resembles Table Rock, in Rogue River valley. The top can only be approached on one side. On the south side there is a narrow ridge, about thirty feet wide and half a mile long. On the top there is a three-square breastwork, partly natural and partly artificial, of stone, it is five or six feet in height, and large enough for one or two hundred men to lie entirely concealed behind it.

We approached this place at sunrise on the morning of the 6th of October, and commenced an attack upon the Indians. The action lasted about six hours, the men taking shelter during the whole time behind the rocks in the rear of the fortification occupied by the Indians.

In this action John Low received a slight wound, and we had one horse killed. However, we captured a horse from the enemy, and killed some eight or ten Indians during the action. The precise number of the enemy is not known, but there must have been, from appearances, not less than one hundred warriors. I was at last compelled to retreat, being entirely unable to route them with my little force.

The next day we travelled up Pi-ute valley fifty miles, and discovered several large ranches that had just been abandoned by the Indians, leaving behind them large quantities of fish and the finest grass seed, which they use for food.

From Pi-ute valley I crossed the Sierra Nevada mountains, about fifty miles north of the immigrant road, and surprised an Indian ranche on the west side of the mountains, in Goose Lake valley, killed two Indians and took one prisoner.

On the 11th of October, with twenty-five men, I again attacked the Indians near Warner’s Rock, and surprised them just at daybreak, after a forced march of forty miles during the night. The action only lasted a few minutes. We took one fine American mare and one prisoner, and killed eight of the enemy. The victory was complete. The enemy were panic-stricken and fled in all directions.

In this action Sergeant Hill was dangerously wounded by a rifle ball passing through his arm, jaw and tongue, breaking his jaw-bone and cutting off a portion of his tongue, which was the only damage we sustained in the battle.

The Pi-utes in the vicinity of the Sierra Nevada mountains are hostile, brave, and very numerous. It will take a large force to conquer them. They are connected with the Snake Indians, and they own one of the finest countries in Oregon. There are beautiful, rich, and productive valleys on both sides of the mountains, immediately north of the immigrant trail, abounding in the finest grasses, and also a great variety of wild herbs, upon which the Indians subsist. These valleys are about one hundred miles in length, running north and south, and from twenty to twenty-five miles in width, and are surrounded by high and rugged mountains on both sides, to which those Indians flee for safety when pursued by the whites.

During the time I was engaged in these expeditions I kept from twenty-five to thirty men on the immigrant trail, guarding trains, under command of Lieutenant Westfeldt, who, I am happy to say, proved himself to be an able and efficient officer. He travelled as far out on the immigrant trail as the Humboldt river, and found the Indians in that vicinity to be very hostile and unfriendly to the whites.

I am informed that among the last of the trains that came down the Humboldt, the Indians near “Gravelly Ford” attacked one of the trains, and took four men and two women prisoners, and after robbing them of everything they had made signal for the immigrants to leave, and as soon as their backs were turned fired upon them, killing two of the men and one woman, and wounding the others. It is therefore indispensably necessary that a strong and efficient force be sent out early next summer to drive the Indians from the immigrant road and conquer them if possible.

I have the honor to be, your most respectful and obedient servant,

JESSE WALKER,

Captain, Commanding Company A, 9th Regiment Oregon Militia.

Jesse Walker died less than a year later on August 18th, 1855, apparently peacefully. It would be years beyond his death, in some cases decades, before his men were paid their full wages.

C. S. Drew’s report to Governor Curry

December 30, 1854

The treacherous conduct of the Indian has at all times, and on all occasions, since the organization of the first American settlements in this Territory, been such as is calculated to deprive them of the sympathy of every true man having the cause of humanity at heart, and to convince the most peaceable of the necessity of their subjugation. The history of the country since the landing of the Pilgrims to the present time proves them wholly unworthy of confidence, and consequent subjects of governmental policy.

The most humane cannot but acknowledge that it is time for vigorous action, and that sickly sentimentality should cease. “Lo! the poor Indian,” is the exclamation of our modern philanthropists and love-sick novel writers. “Lo! the defenceless men, women, and children, who have fallen victims and suffered even more than death itself at their hands,” is the immediate response of the surviving witnesses of the inhuman butcheries perpetrated by this God-accursed race.

The strenuous efforts put forth on the part of the general government to live on amicable terms with the numerous tribes of Indians infesting both the Atlantic and Pacific sea-board has often led to disastrous results.

Treaties, in many instances, have proved disadvantageous to the welfare of the communities in the vicinity of which they have been effected, and the country at large derived little or no benefit from them, except in cases where a thorough subjugation has occurred. Treaties effected under any other circumstances ought not to be relied upon, inasmuch as they are of no validity with the Indian, and they secure to the enemy the privilege of striking the first and oftentimes the fatal blow.

It frequently occurs that many who cherish a generous feeling towards those whom they please to term “the last of a fallen race” fall themselves a sacrifice to their confidence in the good faith and fair promises of the Indian, and are as often murdered with all the circumstances of cruelty and treachery characteristic of the race. To illustrate this fact, we have only to refer to the history of the Eastern and Florida wars, and to that of the subsequent wars of this Territory, particularly to the Rogue River war of 1853, the particulars of which are no doubt familiar to every citizen of Oregon. …

Owing to the limited number of troops stationed on the Pacific coast, which can be made available when the season arrives for the resumption of hostilities, and the urgent demand for troops in other portions of the Union, it seems obvious that the enrollment of a mounted volunteer force will become absolutely necessary.

The Snake river country will, no doubt, require the attention of the government as soon as spring opens, and a concentration at that point of the entire military force now stationed in this vicinity. Unfortunately, however, the military force now stationed here consists principally of infantry, which experience has proved to be inefficient for service in an Indian country; not that they lack the energy, courage, and a hearty good will to render effectual service under any and all circumstances, but for obvious reasons, beyond their control, they are unable to do so; consequently, a volunteer force, even for that section of the country, will no doubt be required.

Nor is the Snake river country the only point from which danger need be apprehended during the coming summer; for, aside from the Indians against whom the expedition was sent in August last, are the Pitt Rivers, a most formidable tribe, who have ever been noted for their unrelenting hostility to the whites, and for the adroitness and skill manifested in their frequent depredations in the settlements and on the highway.

But little fear has been entertained of this tribe heretofore in this Territory; yet, owing to the fact that they are constantly being driven further into the interior by the miners and mountaineers of California, until they are now close upon our borders, at a point, too, in the vicinity of which the annual overland emigration passes en route to southern Oregon, renders it a subject worthy of notice. They, like the Modocs, Piutes, Klamaths, and other tribes in that section of country, have never evinced a desire for peace unless compelled through fear to do so.

Towards this section of country, which has been converted into a battle field for three successive summers past, and in which the most unheard of cruelties and barbarities have been perpetrated upon defenceless citizens, regardless of age, sex, or condition, I most respectfully beg leave to call your early attention, lest it becomes the theatre of the tragical scenes so recently enacted near Fort Boise.

The policy pursued by the federal government in the prosecution of the Florida and other wars of a kindred nature is the only alternative upon which we can safely rely.

Let the requisite number of mounted volunteers be called into the field, dragoons instead of infantry transferred to the Territory, ample funds placed at the disposal of the proper department, and it seems obvious that the impending conflict would soon be ended, and our desire for peace, the security of the lives and property of our citizens, and the promotion of the welfare of the country more than fully realized.

These suggestions, I am aware, will meet opposition on the part of the pseudo-philanthropists, a few of whom have, unluckily, found their way to Oregon, where their presence is so little needed. However, as I have before alluded to this class of fanatics, I now respectfully leave them to their own reflections, with a faint hope that they may soon see themselves as others see them.

There may be those, however, who honestly entertain the belief that volunteer service draws too heavily upon the treasury of the country. Be that as it may, certain it is that volunteers have never been sufficiently compensated to remunerate them for the sacrifices they are compelled to make on leaving home and employment, aside from the dangers and privations they are compelled to encounter while absent. …

In the present emergency every expedient which can be devised and resorted to, of whatever nature, will be required during the coming season to prevent the wanton murders so often perpetrated upon our citizens by the various tribes of Indians occupying the greater portion of the country adjacent to the north Pacific coast.

The prosperity of the country requires that a course of policy be adopted by the government that will at once teach the Indians to feel the power of Americans, and to dread their punishment.

If the treasury of the country will not warrant it, or the prejudices of legislators will not sanction the measures necessary to carry into effect such a policy, whatever it may be, it should be abandoned, at least for a time, or until the period arrives when the proper feelings and motives actuate those to whom our rights are confided. The adoption of the latter policy, though tinctured strongly with anti-progressive Americanism, would throw the citizens of Oregon and vicinity upon their own resources; the effect of which would be the adoption by her citizens of a mode of warfare inconsistent perhaps, in some instances, with the articles of war governing nations, yet altogether more effectual.

The tactics of armies are but shackles and fetters in the prosecution of an Indian war. “Fire must be fought with fire;” and the soldier, to be successful, must, in a great measure, adopt the mode of warfare pursued by the savage.

I remain, very respectfully, your obedient servant,

C. S. DREW,

Quartermaster General O. M.

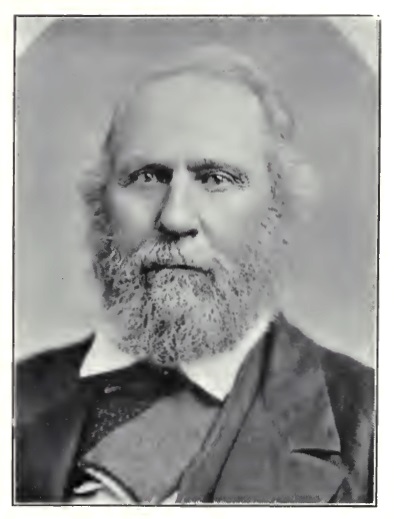

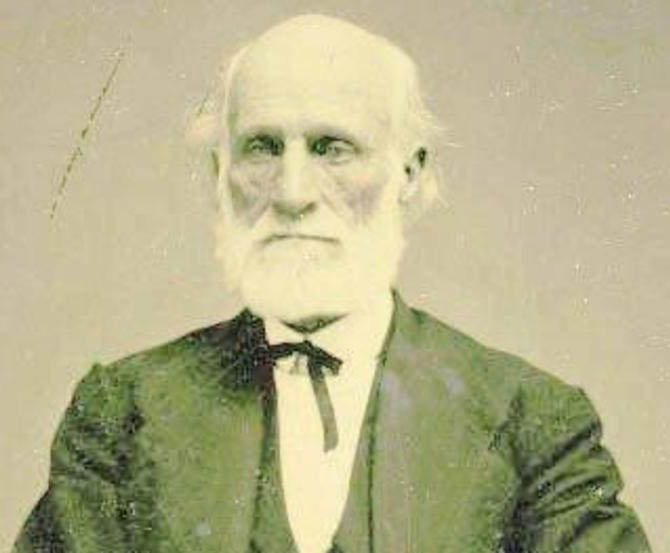

Wilkinson, C., & Wilkinson, C. F:

One of the most compelling figures during the height of the war was John Beeson, a settler in the Rogue River Valley who dared to take up the Indians’ cause. Beeson came west with his family from Illinois, where he was well known for his fervid commitment to abolition and temperance. In 1853 they homesteaded in the Upper Rogue River Valley near present-day Talent and farmed. Never before concerned with Indian matters, he and his son Wellborn found Indian campsites on the property they farmed. Although Beeson knew that the Natives had ceded most of their traditional territory lands to the United States and had been moved to the Table Rock reserve, his occupation of Indian land sat on his conscience. Ever the reformer, John Beeson had found a new cause.

Beeson was captivated by the beauty of the landscape but found most local people to be lawless and ignorant of the nation’s traditions, “for they denied to the poor Indian the common prerogative, peaceful enjoyment of ‘life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.’” Conversations with neighbors and exhortations at public meetings made it clear to him that community leaders had nothing but contempt for their country’s promise of peace in the Table Rock Treaty. People told him that “they should not be satisfied until every Indian was destroyed from the Coast to the Rocky Mountains.” He knew settlers who disagreed, but none dared come forth.

Moralistic and driven, Beeson could not keep his views to himself. He spoke out in community gatherings and wrote letters to Oregon newspapers—and, when they refused to print them, sent them to out-of-state papers. He ran unsuccessfully for the territorial legislature as a defender of Indian rights. In 1855, as vigilantes were about to launch the murderous raid at Little Butte Creek, he urged moderation but, even in the Methodist Church, no one was willing to support him publicly.

In January 1856, he rented a meeting hall in Jacksonville and sent out flyers with the hope of convening a civil discussion on the Indian issue. Nothing of the sort happened, as exterminationists took over the meeting. Other Indian sympathizers had promised to come but did not. Beeson finally gave a long explanation of his views, broken by repeated interruptions, all to no avail:

“The meeting broke up, with but one voice raised in behalf of peace.”

The Rogue River Valley became too dangerous for Beeson. One of his articles in the New York Tribune made the rounds in Jacksonville, as did one addressed to the San Francisco Herald that was intercepted at the local post office. An angry group called a meeting to denounce him, but he was not allowed to present his side to the raucous gathering.

“The following evening, a friend sent me word that the excitement was getting fearfully high. Several companies of Volunteers were discharged. They encamped near my house; and, as I was informed, some of the most reckless among them, were determined on vengeance.”

Beeson’s wife and son, who worried that some would as soon “kill him as an Indian just because he has spoken the truth out bold,” agreed there was only one course. Beeson left home in the dark of night and made it to Fort Lane, where he received a military escort north to safety in the Willamette Valley. Other than a visit, probably in 1868, he did not return to Talent until the early 1880s. He died there in 1889.

John Beeson’s midnight escape hardly ended his career as a defender of American Indians. Lecturing widely in the East and publishing many articles and pamphlets, he gained some national prominence. Were it not for Oregon senators Harding and Nesmith, who blocked his nomination, he might have become the Commissioner of Indian Affairs.

But John Beeson’s greatest legacy was his thin volume, A Plea for the Indians, where he set out in full his views on the Rogue River War in particular and Indian Affairs in general. Anchored in his own day-to-day experiences and personal contacts in the crucible of the most violent years of the war, the book carried authenticity. While he documented violence by the whites, he did so as a pious man who came forth out of duty:

“If at every point of this melancholy story, I awake unfavorable reflections on the conduct of our fellow-countrymen, it is not because I either will or wish it. Would to God I had sufficient authority to do otherwise. But feeling as I do, that the Indian, though of a different Race, is a brother of the same great family, I should not be true to our common nature were I to withhold a faithful statement of the wrongs I have witnessed.”

For Beeson, Americans failed to receive the truth because of the way that the zeal and influence of the local exterminationists controlled the debate. If the public had received the truth, “surely this state of things could not long exist. The impulsive humanity of the Nation would rise against it. And, doubtless, the reason why there is so little done, is, for the want of data, as to facts.” Instead, public impression was driven by “the varied statements, almost all of them overcharged with a cruel and bitter prejudice against the Indians, who cannot write, or proclaim their own grievances by any competent mode of speech.”

A Plea for the Indians attempted to set the record straight. Beeson disputed the accuracy of some alleged Indian attacks on whites, but more fundamentally he put the Indian-white conflict in a broader context. Repeatedly, he showed, the tribes were not the aggressors: their attacks were made in “self-protection.”

“The main body of Indians,” Beeson wrote, “evidently acted with the greatest discretion, keeping entirely on the defensive.”

Even given their superiority in terms of rifle power and knowledge of the land, the tribes wanted peace. Had the Indians been disposed to destroy and slaughter all they could, there would have been hardly a house left in the Valley; and it was often a subject of remark, that they did so little damage. And so far as Volunteers and Forts were concerned, many thought that fifty determined Indians, bent on their object, could have overthrown and burned the whole in a week.

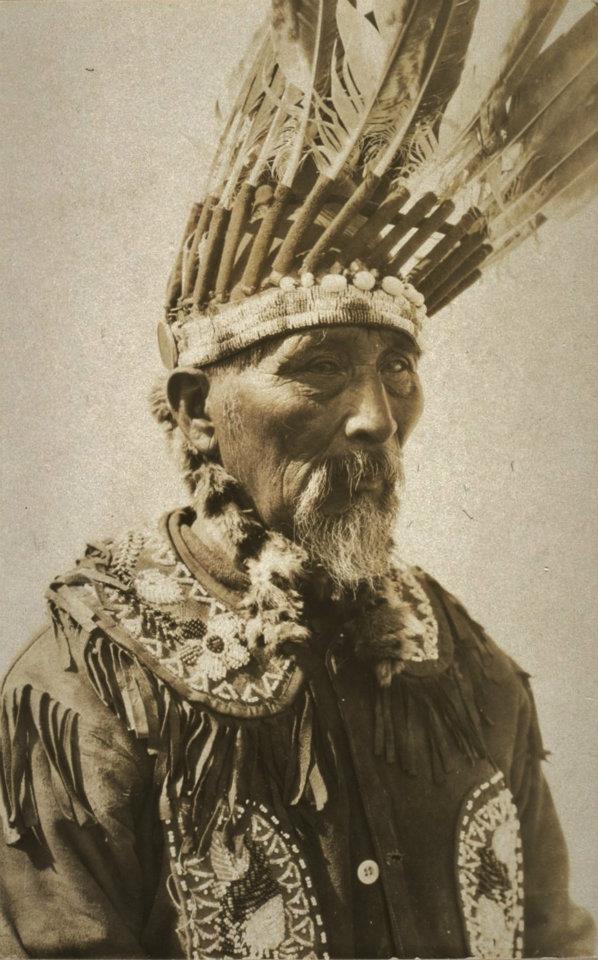

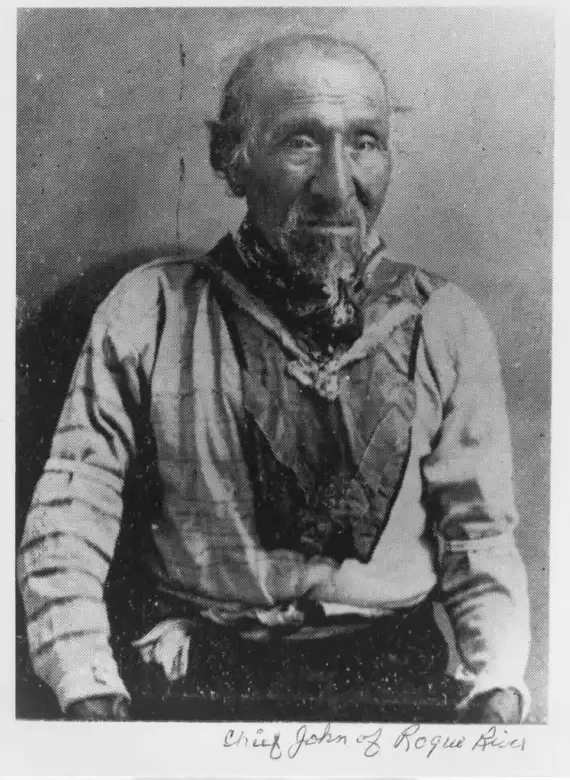

To illustrate the motives of the tribes and his central belief in the humanity of Indian people, Beeson used as example Tyee John, the great Shasta war leader during the war years of 1855 and 1856. Beeson described John as “a very sagacious and energetic man. He was greatly esteemed by his people, and under ordinary circumstances would have commanded respect in any community.” John, who appreciated the importance of diplomacy and signed the Table Rock Treaty, “was faithful in the observance of the treaty, and often lamented the necessity his people were under [in] retaliating upon the Whites.”

Tyee John, while an exceptional warrior—Binger Hermann wrote that “of all the Pacific Coast Indians Chief John ranks as the ablest, most heroic and most tactical of chieftains”—was committed to the rules of war and knew that the regular officers in the army acted accordingly. His trust was not always rewarded. Beeson recounted an incident where miners in California accused John’s son and a fellow tribesman of murder. John knew them to be innocent. So did Captain Andrew Smith, but duty required him to have the case tried in a United States court in Yreka, California.

John reluctantly agreed. The grand jury refused to issue an indictment against the two Indian men but on the way back to Oregon, with a military escort and through no fault of Smith’s or the other officers, the miners caught the guards by surprise and brutally murdered the two men. John Beeson eloquently put forth the confusion and deeply held sense of injustice that Tyee John and other Native people endured in this terrible clash of cultures:

“When the aged Chief became acquainted with the fate of his son and his companion, he was astonished and outraged, beyond the power of language to describe; for he had had full confidence in the sincerity and power of the Military to secure their present protection and ultimate justice. He had been impressed with the idea that our Great Father, the President, and all his men, the Soldiers, were the Red Man’s friends; but, in the bitterness of grief, he saw that they were either unable or unwilling to save them from their enemies. He had long foreseen the gradual but certain destruction of his people; but he now saw that the great train of extermination was in rapid progress. Another conviction was also forced upon him. He saw that the ‘bad Bostons’ were no more under the control of the Great Father, than bad Indians were under his own… Will any one who believes that man has a right to defend himself, say that the Chief had not the strongest and truest reason for war? Compared with his wrongs, the petty infringements of which our Fathers complained sink into insignificance and become trivial.”

The first week in October was “court week,” and Judge Matthew Deady traveled to Jacksonville for hearings, which drew people to town. Extermination talk filled the air. The regular army gave no support to the crowd—General Wool’s disdain for the volunteers was well known. At Fort Lane, Captain Andrew Smith knew how much generalized anger was directed toward the Indians, most of whom wanted peace. He saw his primary duty as protecting the Natives on the reservation. This left the field to Major James Lupton. Like many “majors,” “lieutenants,” and “colonels” in the volunteer armies, he had no formal military title—the locals had bestowed “major” on him. This was one of the many cases in which “volunteers” was a euphemism: Lupton’s recruits were vigilantes, a mob, thugs.

Their target was a band of Table Rock Indians living in brush huts at their traditional summer camping site near the mouth of Little Butte Creek. They were off the reservation, which was for the Indian Office and the army to enforce, but otherwise they had done nothing wrong. Lupton called two meetings in Jacksonville to propose his attack. John Beeson rode up from Talent for the meetings and at the second implored the group not to go ahead. No one backed him up.

I arose, and spoke with all the feeling, and all the power I had, in the behalf of the poor Indians. . . . I begged them, by every principle of humanity and justice, to inflict no wrong upon the helpless. . . . I strongly urged them, as citizens and Christians, to raise a voice of remonstrance, or to call on the Authorities for the administration of justice, and thus avert the impending calamity.

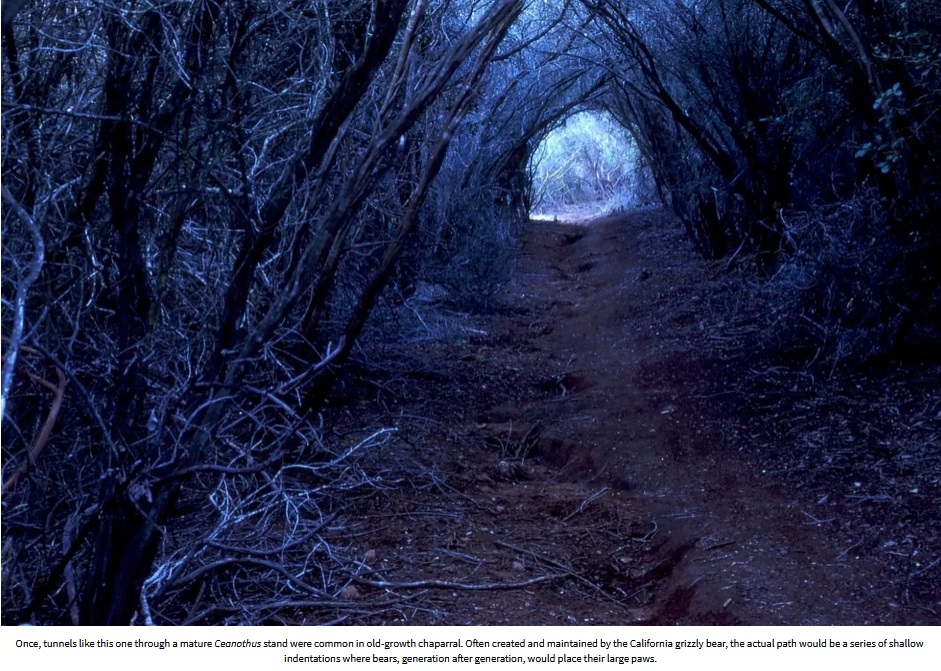

The summer village site at Little Butte Creek was close to the reservation, within sight of Upper Table Rock. Small grassy openings, where the Natives constructed their lodges, were hemmed in by thick vegetation—an undergrowth of vine maple and a tall canopy of oaks and willows reaching up a hundred feet or more. But if it was well protected, it was hard to see out: Little Butte Creek enters the Rogue out in the flats of the main valley so that the creek and its banks made only a shallow indentation in the landscape. There was no nearby high ground for a lookout.

As they had vowed to do at the second meeting in Jacksonville, the exterminators raided the Indians on Little Butte Creek on October 8, 1855. Some forty vigilantes crept to the perimeter of the village during the dark and made their charge before the sun rose. Although Lupton took a fatal arrow to the chest and another raider died, all the other dead were Indians. “Lupton and his party fired a volley into the crowded encampment, following up the sudden and totally unexpected attack by a close encounter with knives, revolvers, and whatever weapon they were possessed of. . . . These facts are matters of evidence, as are the killing of several squaws, one or more old decrepit men, and a number, probably small, of children.”

There is no precise count of the carnage. Beeson reported “twenty-eight bodies, fourteen being those of women and children. But as many dead were undoubtedly left in the thickets, and no account was taken of the wounded, many of whom would die, or of the bodies that were afterward seen floating in the river, the above must be far short of the number actually killed.” One newspaper account reported forty Indian casualties. Captain Smith estimated eighty. Joel Palmer received a report that one hundred and six Indian people had been killed.

The next sequence of events that deserves notice constitutes the “Humbug War,” well known by that name in Northern California. The whole matter, which at one time threatened to assume serious proportions, grew out of a plain case of drunk. Two Indians–whether Shastas, Klamaths, or Rogue Rivers there is no evidence to show, but presumably from the locality of the former tribe–procured liquor and became intoxicated, and while passing along Humbug Creek in California, were met by one Peterson, who foolishly meddled with them. Becoming enraged, one of the Indians shot him, inflicting a mortal wound; as he fell he drew his own revolver and shot his opponent in the abdomen.

The Indians started for the Klamath River at full speed, while the alarm was given. Two companies of men were instantly formed and sent out to arrest the perpetrators. The information that an Indian had shot a white man was enough to arouse the whole community, and no punishment would have been deemed severe enough for the culprit if he had been taken. The citizens found on the next day a party of Indians who refused to answer their questions as they wished, so they arrested three of them and set out for Humbug with them.

While on the road, two of the three escaped, the other one was taken to Humbug, examined before a justice of the peace and for want of evidence discharged. When the two escaped prisoners returned to their camp, it was the signal for a massacre of whites. That night (July 28) the Indians of that band passed down the Klamath, killing all but three of the men working between Little Humbug and Horse creeks. Eleven met their death at that time, being William Hennessy, Edward Parish, Austin W. Gay, Peter Hignight, John Pollock, four Frenchmen and two Mexicans.

Excitement knew no bounds; every man constituted himself an exterminator of Indians, and a great many of that unfortunate race were killed, without the least reference to their possible guilt or innocence. Many miserable captives were deliberately shot, hanged or knocked into abandoned prospect holes to die. Over twenty-five natives, mostly those who had always been friendly, were thus disposed of. Even infancy and old age were not safe from these “avengers,” who were composed chiefly of the rowdy or “sporting” class. …

On the seventh of October, 1855, a party of men, principally miners and men-about-town, in Jacksonville, organized and armed themselves to the number of about forty (accounts disagree as to number), and under the nominal leadership of Captain Hays and Major James A. Lupton, representative-elect to the territorial legislature, proceeded to attack a small band of Indians encamped on the north side of Rogue River near the mouth of Little Butte Creek a few miles above Table Rock.

Lupton, it appears, was a man of no experience in bush fighting, but was rash and headstrong. His military title, says Colonel Ross, was unearned in war and was probably gratuitous. It is the prevailing opinion that he was led into the affair through a wish to court popularity, which is almost the only incentive that could have occurred to him. [A greater motivation would be the close proximity of Lupton’s bachelor cabin to an Indian village–the one that suffered the brunt of the massacre.] Certainly it could not have been plunder; and the mere love of fighting which probably drew the greater part of the force together was perhaps absent in his case.

The reason why the particular band at Butte Creek was selected as victims also appears a mystery, although the circumstances of their location being accessible, their numbers small, and their reputation as fighters very slight, possibly were the ruling considerations. This band of Indians appears to have behaved themselves tolerably; they were pretty fair Indians, but beggars, and on occasion thieves. They had been concerned in no considerable outrages that are distinctly specified. The attacking party arrived at the river on the evening of the seventh, and selecting a hiding place, remained therein until daylight, the appointed time for the attack.

The essential particulars of the fight which followed are, when separated from a tangle of contradictory minutiae, that Lupton and his party fired a volley into the crowded encampment, following up the sudden and totally unexpected attack by a close encounter with knives, revolvers, and whatever weapon they were possessed of, and the Indians were driven away or killed without making much resistance. These facts are matters of evidence, as are also the killing of several squaws, one or more old decrepit men, and a number, probably small, of children.

The unessential particulars vary greatly. For instance, Captain Smith reported to government that eighty Indians were slaughtered. Other observers, perhaps less prejudiced, placed the number at thirty. Certain accounts, notably that contributed to the Statesman by A. J. Kane, denied that there were any “bucks ” present at the fight, the whole number of Indians being women, old men, and children. It is worth while to note that Mr. A. J. Kane promptly retracted this supposed injurious statement, and in a card to the Sentinel said he believed there were some bucks present. Certain “Indian fighters” also appended their names to the card.

The exact condition of things at the fight, or massacre, as some have characterized it,is difficult to determine. Accounts vary so widely that by some it has been termed a heroic attack, worthy of Leonidas or Alexander; others have called it an indiscriminate butchery of defenseless and peaceful natives, the earliest possessors of the soil. To temporize with such occurrences does not become those who seek the truth only, and the world would be better could such deeds meet at once the proper penalty and be known by their proper name.

Whether or not Indian men were present does not concern the degree of criminality attached to it. The attack was indiscriminately against all. The Indians were at peace with the whites and therefore unprepared. To fitly characterize the whole proceeding is to say that it was Indian-like.

The results of the matter were the death of Lupton, who was mortally wounded by an arrow which penetrated his lungs, the wounding of a young man, Shepherd by name, the killing of at least a score of Indians, mainly old men, and the revengeful outbreak on the part of the Indians, whose account forms the most important part of this history. …

The ninth of October, 1855, has justly been called the most eventful day in the history of Southern Oregon. On that day nearly twenty persons lost their lives, victims to Indian ferocity and cruelty. Their murder lends a somber interest to the otherwise dry details of Indian skirmishes, and furnishes many a romantic though saddening page to the annalist who would write the minute history of those times.

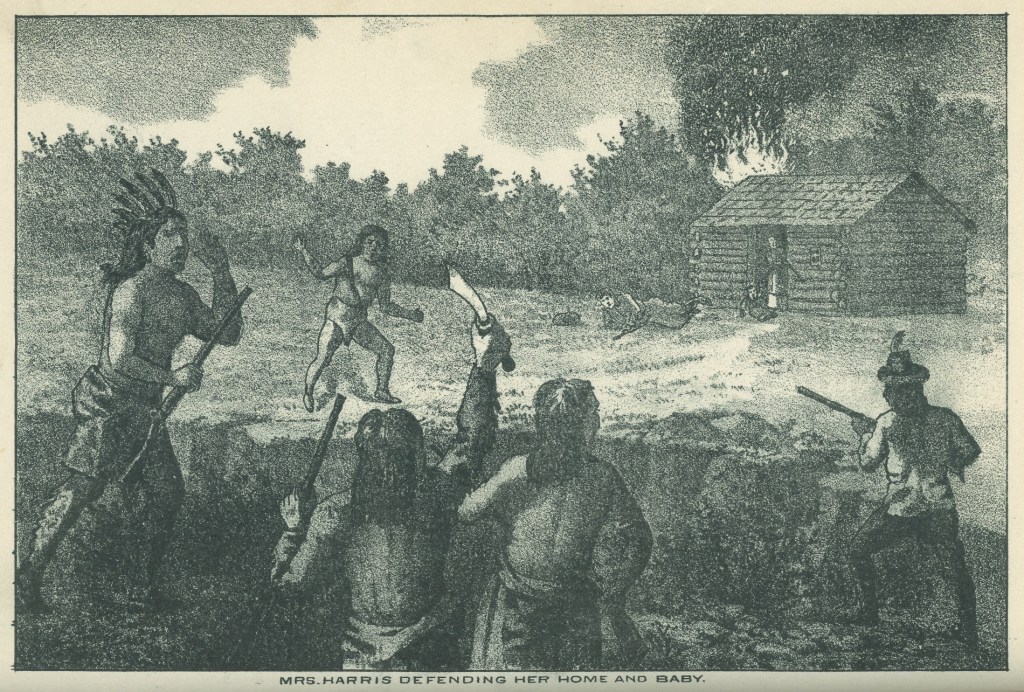

A portion of the incidents of that awful day have been written for publications of wide circulation, and thus have become a part of the country’s stock-in-trade of Indian tales. Certain of them have taken their place in the history of our country along with the most stirring and romantic episodes of border warfare. Many and varied are this country’s legends of hairbreadth escapes and heroic defense against overpowering odds. There is nothing told in any language to surpass in daring and devotion the memorable defense of the Harris home. Mrs. Wagoner’s mysterious fate still bears a melancholy interest, and while time endures the people of this region cannot forget the mournfully tragic end of all who died on that fateful day.

As the present memories describe it, the attack was by most people wholly unexpected, in spite of the previous months of anxiety. The recklessness of the whites who precipitated the outbreak by their conduct at the Indian village above Table Rock had left unwarned the outlying settlers, upon whose defenseless and innocent heads fell the storm of barbaric vengeance.

Early on the morning of October ninth, the bands of several of the more warlike chiefs gathered at or near Table Rock, set out traveling westward, down the river, and transporting their families, their arms and other property, and bent on war. It is not at this moment possible to ascertain the names of those chiefs, nor the number of their braves; but it has been thought that Limpy, the chief of the Illinois band, with George, chief of the lower Rogue river band, were the most prominent and influential Indians concerned in the matter. [During the war Indian agent Ambrose sent emissaries to the Indians’ camp and learned that all the attacks along the Rogue River were committed by Chief John and eight confederates. See his letter of February 18, 1856.] Their numbers, if we follow the most reliable accounts, would indicate that from thirty-five to fifty Indians performed the murders of which we have now to discourse.

Their first act was to murder William Goin or Going, a teamster, native of Missouri, and employed on the reservation, where he inhabited a small hut or house. Standing by the fireplace in conversation with Clinton Schieffelin, he was fatally shot, at two o’clock in the morning. The particular individuals who accomplished this killing were, says Mr. Schieffelin, members of John’s band of Applegates, who were encamped on Ward Creek, a mile above its mouth, and twelve miles distant from the camp of Sam’s band.

Hurrying through the darkness to Jewett’s ferry these hostiles, now reinforced by the band of Limpy and George, found there a pack train loaded with mill irons. Hamilton, the man in charge of it, was killed, and another individual was severely wounded, being hit in four places. They next began firing at Jewett’s house, within which were several persons in bed, it not being yet daylight. Meeting with resistance they gave up the attack and moved to Evans’ ferry, which they reached at daybreak. Here they shot Isaac Shelton, of Willamette Valley, en route for Yreka. He lived twenty hours.

The next victim was Jones, proprietor of a ranch, whom they shot dead near his house. His body was nearly devoured by hogs before it was found. The house was set on fire, and Mrs. Jones was pursued by an Indian and shot with a revolver, when she fell senseless, and the savage retired, supposing her dead. She revived and was taken to Tufts’ place and lived a day.

O. P. Robbins, Jones’ partner, was hunting cattle at some distance from the house. Getting upon a stump, he looked about him and saw the house on fire. Correctly judging that Indians were abroad, he proceeded to Tufts and Evans’ places and secured the help of three men, but the former place the Indians had already visited and shot Mrs. Tufts through the body, but being taken to Illinois Valley she recovered.

Six miles north of Evans ferry the Indians fell in with and killed two men who were transporting supplies from the Willamette Valley to the mines. They took the two horses from the wagon, and went on. The house of J. B. Wagoner was burned, Mrs. Wagoner being previously murdered, or, as an unsubstantiated story goes, she was compelled to remain in it until dead. This is refinement of horrors indeed. For a time her fate was unknown, but it was finally settled thus. Mary, her little daughter, was taken to the Meadows, on lower Rogue River, some weeks after, according to the Indians’ own accounts, but died there. Mr. Wagoner, being from home, escaped death.

Coming to Haines’ house, Mr. Haines being ill in bed, they shot him to death, killed two children and took his wife prisoner. Her fate was a sad one, and is yet wrapped in mystery. It seems likely, from the stories told by the Indians, that the unhappy woman died about a week afterwards, from the effects of a fever aggravated by improper food. When the subsequent war raged, a thousand inquiries were made concerning the captive, and not a stone was left unturned to solve the mystery. The evidence that exists bearing upon the subject is unsatisfactory indeed, but may be deemed sufficiently conclusive.

At about nine o’clock a.m., the savages approached the house of Mr. Harris, about ten miles north of Evans, where dwelt a family of four–Mr. and Mrs. Harris and their two children, Mary aged twelve, and David aged ten years. With them resided T. A. Reed, an unmarried man employed by or with Mr. Harris in farm work. Reed was some distance from the house, and was set upon by a party of the band of hostiles and killed, no assistance being near. His skeleton was found a year after.

David, the little son of the fated family, had gone to a field at a little distance, and in all likelihood was taken into the woods by his captors and slain, as he was never after heard of. Some have thought that he was taken away and adopted into the tribe–a theory that seems hardly probable, as his presence would have become known when the entire band of hostiles surrendered several months afterward. It seems more probable that the unfortunate youth was taken prisoner, and proving an inconvenience to his brutal captors, was by them unceremoniously murdered and his corpse thrown aside, where it remained undiscovered.

Mr. Harris was surprised by the Indians, and retreating to the house, was shot in the breast as he reached the door. His wife, with the greatest courage and presence of mind, closed and barred the door, and in obedience to her wounded husband’s advice, brought down the firearms which the house contained–a rifle, a double shotgun, a revolver and a single-barreled pistol–and began to fire at the Indians, hardly with the expectation of hitting them, but to deter them from assaulting or setting fire to the house. Previous to this a shot fired by the Indians had wounded her little daughter in the arm, making a painful but not dangerous flesh wound, and the terrified child climbed to the attic of the dwelling, where she remained for several hours.

Throughout all this time the heroic woman kept the savages at bay, and attended as well as she was able to the wants of her fearfully wounded husband, who expired in about an hour after he was shot. Fortunately, she had been taught the use of firearms; and to this she owed her preservation and that of her daughter. The Indians, who could be seen moving about in the vicinity of the house, were at pains to keep within cover and dared not approach near enough to set fire to the dwelling, although they burned the outbuildings, first taking the horses from the stable.

Mrs. Harris steadily loaded her weapons, and fired them through the crevices between the logs of which the house was built. In the afternoon, though at what time it was impossible for her to tell, the Indians drew off and left the stouthearted woman mistress of the field. She had saved her own and her daughter‘s life, and added a deathless page to the record of the country’s history.

After the departure of the savages, the heroine with her daughter left the house and sought refuge in a thicket of willows near the road, and remained there all night. Next morning several Indians passed, but did not discover them, and during the day a company of volunteers, hastily collected in Jacksonville, approached, to whom the two presented themselves, the sad survivors of a once-happy home.

When, on the ninth of October, a rider came dashing into Jacksonville and quickly told of the fray, great excitement prevailed, and men volunteered to go to the aid of whoever might need help. Almost immediately a score of men were in their saddles and pushing toward the river. Major Fitzgerald, stationed at Fort Lane, went or was sent by Captain Smith, at the head of fifty-five mounted men, and these going with the volunteers, proceeded along the track of ruin and desolation left by the savages.

At Wagoner’s house, some five or six volunteers who were in advance came upon a few Indians hiding in the brush nearby, who, unsuspicious of the main body advancing along the road, challenged the whites to a fight. Major Fitzgerald came up and ordered a charge; and six of the “red devils” were killed, and the rest driven “on the jump” to the hills, but could not be overtaken.

Giving up the pursuit, the regulars and volunteers marched along the road to the Harris house, where, as we have seen, they found the devoted mother and her child, and removed them to a place of safety in Jacksonville. They proceeded to and camped at Grave Creek that night, and returned the next day.

A company of volunteers led by Captain Rinearson hastily came from Cow Creek, and scoured the country about Grave Creek and vicinity, finding quite a number of bodies of murdered men. On the twenty-fifth of October the body of J. B. Powell, of Lafayette, Yamhill County, was found and buried. James White and —— Fox had been previously found dead. All the houses along the Indians’ route had been robbed and then burned, with two or three exceptions.

It would be difficult to picture the state of alarm which prevailed when the full details of the massacre were made known. Self-preservation, the first law of nature, was exemplified in the actions of all. The people of Rogue River Valley, probably without exception, withdrew from their ordinary occupations and “forted up” or retired to the larger settlements. Jacksonville was the objective point of most of these fugitives, who came in on foot, on horse or mule back, or with their families or more portable property loaded on wagons drawn by oxen.

In every direction mines were abandoned, farms and fields were left unwatched, the herdsman forsook his charge, and all sought refuge from the common enemy. The industries which had suffered a severe but only temporary check in the summer of 1853 were again brought to a standstill, and the trade and commerce which were rapidly building up Jackson and her neighboring counties became instantly paralyzed. All business and pleasure were forsaken, to devise means to meet and vanquish the hostile bands. …

To oppose such an array of active murderers and incendiaries, the general government had a small number of troops unfitted to perform the duties of Indian fighting by reason of their unsuitable mode of dress, tactics and their dependence upon quartermaster and commissary trains. The fact has been notorious throughout all the years of American independence that the regular army, however brave or well officered, has not been uniformly successful in fighting the Indians. The reasons for this every frontiersman knows. … But upon such troops the government in 1855 relied to keep peace between the hostile white and Indian population in Southern Oregon, and although with final success, we shall see that the operation of subduing the Indians was needlessly long and tedious.

We shall also see how an ill-organized, unpaid, ill-fed, ill-clothed and insubordinate volunteer organization, brought together in as many hours as it required weeks to marshal a regular force, dispersed the savages repeatedly, fought them wherever they could be found, and in the most cheerless days of winter resolutely followed their inveterate foe, and were “in at the death” of the allied tribes.

The formation of volunteer companies and the enrollment of men began immediately upon the receipt of the news of the outbreak. The chief settlements–Jacksonville, Applegate Creek, Sterling, Illinois Valley, Deer Creek, Butte Creek, Galice Creek, Grave Creek, Vannoy’s ferry, and Cow Creek–became centers of enlistment, and to them resorted the farmers, miners, and traders of the vicinity, who with the greatest unanimity enrolled themselves as volunteers to carry on the war which all now saw to be unavoidable.

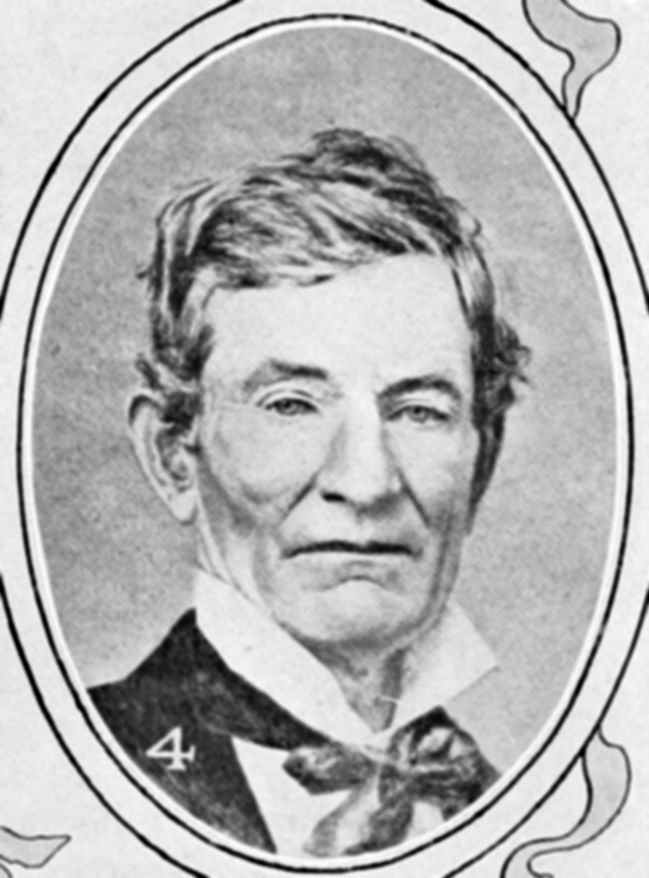

On the twelfth of October, John E. Ross, Colonel of the Ninth Regiment of Oregon militia, assumed command of the forces already raised, by virtue of his commission, and in compliance with a resolution of the people of Jacksonville and vicinity. …

It is justly thought remarkable that such a force could have been raised in a country of such a limited population as Southern Oregon; and this fact is rendered still more remarkable by the extreme promptness with which this respectable little army was gathered.

If we examine the muster rolls of the different companies, we shall be struck by the youth of the volunteers–the average age being not beyond twenty-four years. From all directions they came, these young, prompt and brave men, from every gulch, hillside and plain, from every mining claim, trading post and farm of this extensive region, and from the sympathizing towns and mining camps of Northern California, which also sent their contingents.

Thus an army was gathered, able in all respects to perform their undertaking of restoring peace, and suddenly too. These troops, as already said, were mounted. Their animals were gathered from pack trains, farms and towns, and were in many cases unused to the saddle. But the exigencies of war did not allow the rider to hesitate between a horse and a mule, or to humor the whims of the stubborn mustang or intractable cayuse.

With the greatest celerity and promptness the single organizations had hurried to the rescue of the outlying settlements and in many cases preserved the lives of settlers menaced by Indians.

Hubert Howe Bancroft:

One whole night I spent with Ross at Jacksonville, writing down his experiences; and when at early dawn my driver summoned me, I resumed my journey under a sickening sensation from the tales of bloody butcheries in which the gallant colonel had so gloriously participated.

General John E. Wool, commander, Department of the Pacific:

September 1855

I am informed that the inhabitants of Jacksonville and its vicinity are bent on carrying out their threats to exterminate the unoffending Indians… This is not a war for protection, but a war of extermination, for the sake of the profit to be derived from it, and to get possession of the Indian lands.

William G. T’Vault, Table Rock Sentinel:

10-13-55

We suppose from past and present indications we must have another general war with these savages, which must be a war of extermination to ensure anything like a lasting peace.

Joel Palmer:

10-20-55

Intense excitement pervades the white population of the entire country, and in the districts most remote the people have congregated in blockhouses and forts which they have erected for their protection. Messengers are seen hurrying from settlement to settlement, alarming reports are everywhere current, and in the popular frenzy the peaceful as well as the hostile bands of Indians are menaced with extermination. The demonstrations already made in Jackson County and in the Umpqua Valley arouse the fears of the Indians in this part of the Territory that these threats may be carried into execution.

However, the collection of the Indians at suitable points, and the appointment of discreet persons to watch over them, has tended very much to quiet their apprehensions, but should the present campaign in Washington Territory and in Middle Oregon prove unsuccessful, it will be well nigh impossible to save the Indians of this valley from the fury of the inhabitants.

Their guilt or innocence will not be the subject of inquiry; the fact that they are Indians will be deemed deserving of death. They will be slain, not for what they have done, but for what they might do if so disposed.

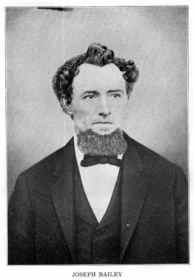

Captain Joseph Bailey, commander company A, 2nd Regiment, Oregon Mounted Volunteers (Southern Battalion):

Nov 3, 1855

SIR: In obedience to your order, I moved with my command from this place on the night of the 30th ultimo, in company with the command of Captain Smith, of the United States army, and the other companies of the volunteer service, to attack the Indians in their stronghold in the mountains. We reached the vicinity of their camp at daybreak on the 31st, and immediately prepared for action.

The mountains are covered with a dense growth of chaparral and manzanita, which rendered it utterly impossible to move a body of men through it with any degree of order. We were obliged to crawl on our hands and knees in many places, and the Indians, being perfectly familiar with the ground, had every advantage.

The engagement commenced at about 6 o’clock in the morning, and continued with great fury during the entire day. The ground was such that it was impossible for the men to form in any kind of order, or even to see the enemy. We were in a position where we were constantly picked off without the possibility of returning the fire with any effect. I found it necessary to withdraw the men to a place of safety to prevent a total sacrifice of the command.

The men are destitute of provisions and blankets. We have been in the mountains since the 29th without any supply reaching us. The suffering for want of water and food is such that the men are becoming unfit for duty. My command returned to this place today, bringing in the wounded with great difficulty. The men and horses are entirely broken down by the excessive fatigue and the nature of the country through which we have passed.

The Oregon Statesman:

November 4, 1855

The war in the South has become a real and earnest affair. The battle in the Grave Creek hills has proved most disastrous to our side. It is supposed that there were not more than 100 fighting Indians engaged in the action. On our side were over 300 volunteers and more than 100 regulars. The loss on the side of the Indians was very trifling, probably not more than 7 or 8 killed.