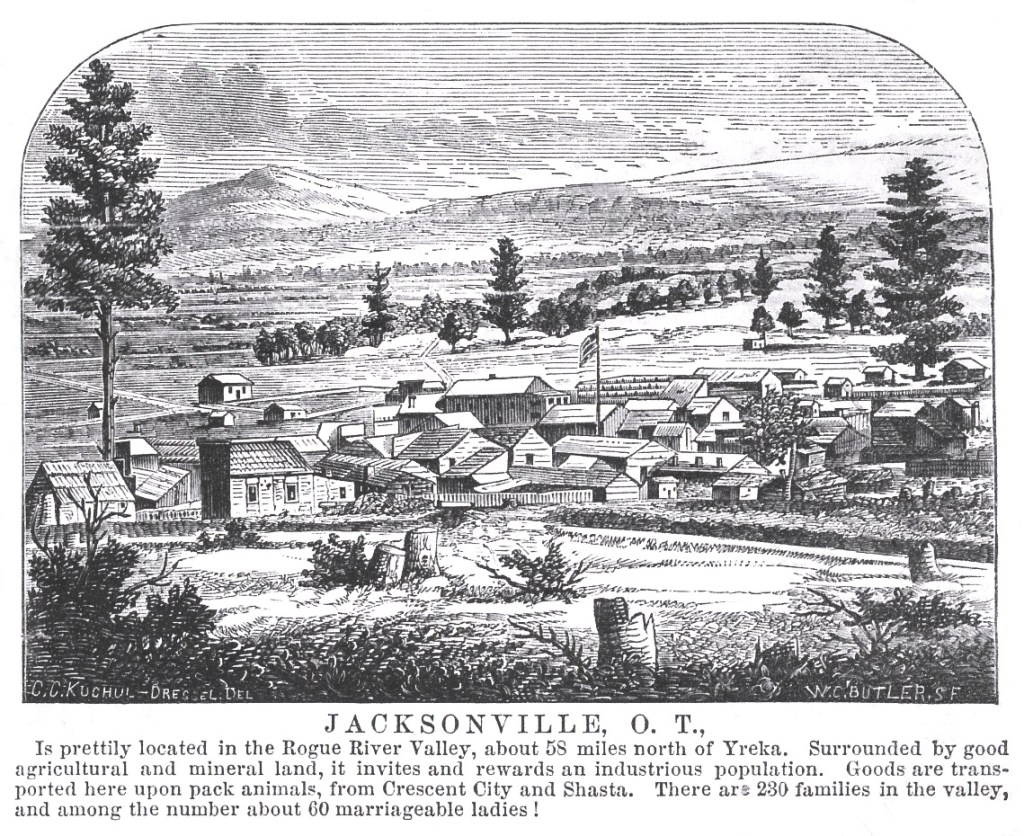

Previously: In 1853, Johnnie Smith went overland from Yreka, California, to Jacksonville, Oregon.

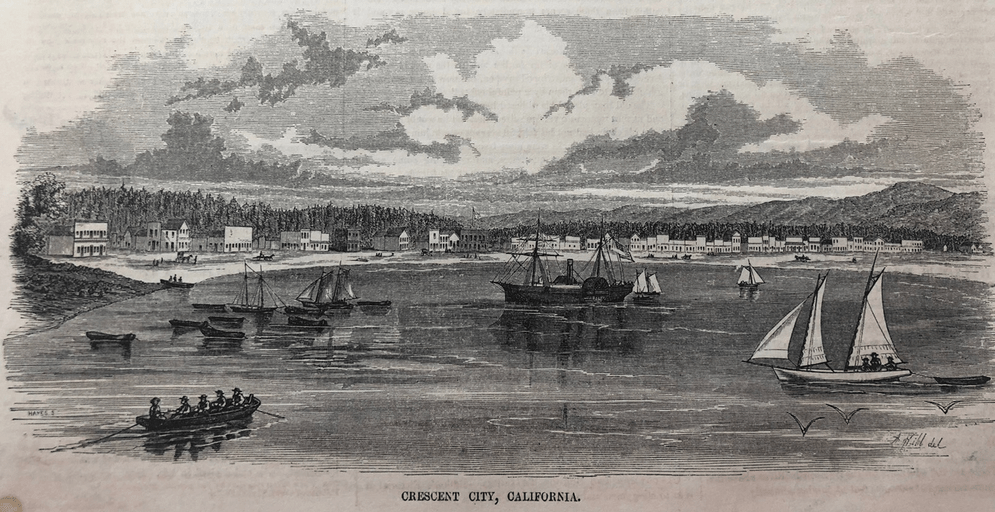

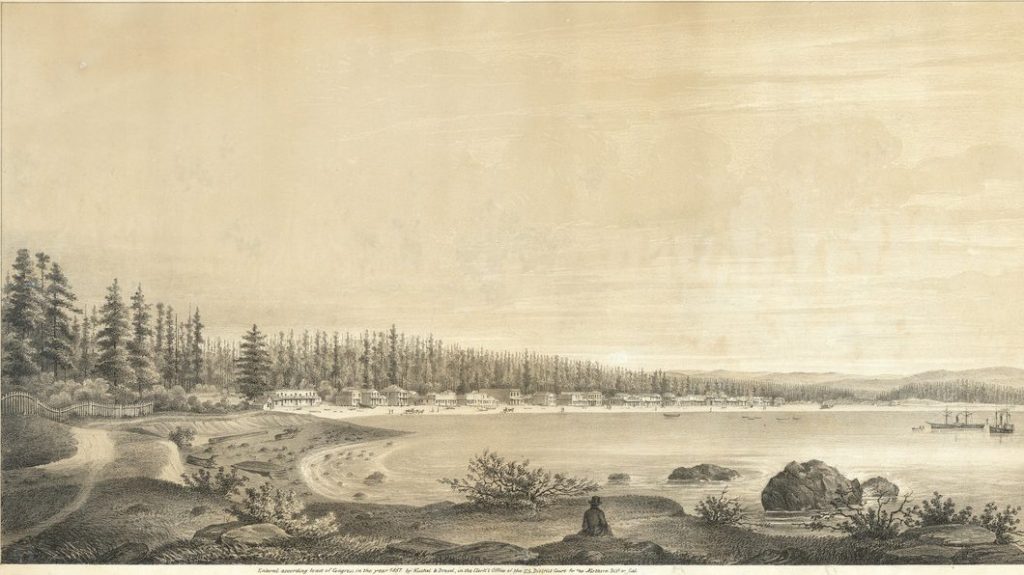

At Jacksonville, I freighted from Crescent City, on the coast near the California line, to Jacksonville.

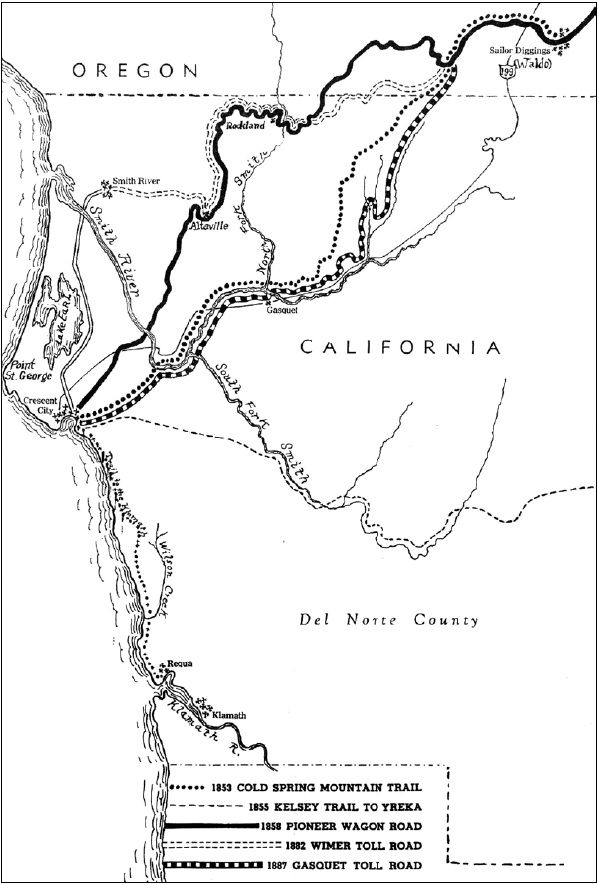

Jacksonville had to be supplied from coastal ports. Until 1853, this meant coming all the way from Portland or Sacramento, roughly 300 miles either way. With the establishment of Crescent City, the distance shipping goods overland was reduced to 110 miles. By May of 1853 the city was up and running as the primary supply hub to the region .

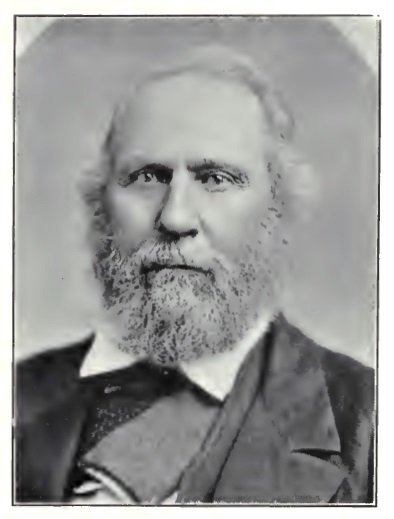

George McKinley and Doug Frank:

After the gold rush of 1849, northern California was brimming with wouldbe and has-been gold-seekers flowing in, out of, and around San Francisco.

The possibility of taking ship passage to the Crescent City area and joining the next gold rush to Sailors’ Diggings and Jacksonville made the development of a western route, from Crescent City to Jacksonville, attractive.

By 1853, that route was developed up the Smith River and over the divide into Oregon. In very short order, the route was extended to Kerby, where it veered east and then north over a low divide into Deer Creek. From there it ascended Crooks Creek below Mooney Mountain and descended Cheney Creek to the Applegate River. It crossed the Applegate by way of a ferry service that operated near the present Fish Hatchery Bridge.

With the activity in the Jackson Creek, Jackass Creek and Sterling Creek mines at full tilt, this first southern Oregon thoroughfare was very soon extended all the way to Jacksonville. In its earliest form, it followed the north bank of the Applegate River upstream about 28 miles before crossing the divide into Jacksonville.

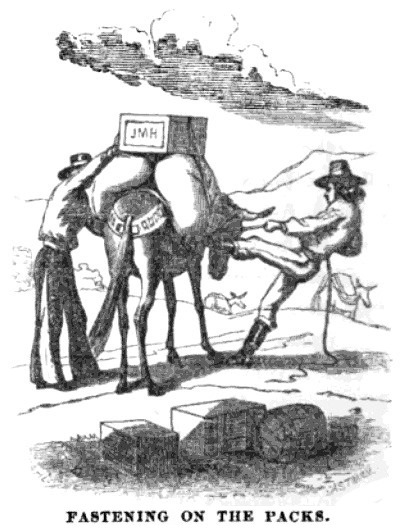

For several years, this was an important travel artery for the study area. It brought miners, settlers, and supplies eastward from travel routes on the Coast, and it carried agricultural goods to the port at Crescent City for shipment to San Francisco. For most of that first decade, it was not much more than a broad trail used for foot and mounted traffic and mule trains.

By 1855, between fifty and two hundred pack mules may have traversed this route daily. Some of the drivers on the Crescent City-to-Jacksonville route were professionals. Often Mexicans in the early years, Indians in the later, they represented a western breed who followed the rising demands for packers across the expanding frontier. Others were exhausted or failed miners. One of these was John Tice, an immigrant from Indiana. Tice first passed through the Rogue Valley in 1851, at the age of nineteen. He had little success in mining, so he began packing. Letters he sent back to his parents offer a glimpse of life among the early packers.

Tice ran a pack train of about fifteen mules on the route from Crescent City to the gold fields. “It is a little over one hundred miles from here to Crescent City,” he wrote from Jacksonville, and the round trip took him two or three weeks. <…> “Packing is dirty, disagreeable work,” he wrote in 1853, “but it pays us good wages.

There was no wharf at Crescent City, so goods had to be offloaded on small boats, “lightered” to shore. Supplies were then transported overland via pack animal trains along a rough footpath to Jacksonville and other inland settlements.

There is no good harbor at Crescent City. It was formerly called Paragon Bay after a small brig of that name that parted her cables while sitting at anchor there and drifted ashore and was lost. A bend of the coast inward forms a crescent at the northmost point. There is a rather high bluff of rocks and off the bluff down the coast there are several more islands and rocks. This is about what forms the harbor at Crescent City. It is not safe for large vessels. But I think it would be fine for any other vessel to anchor there.

On the beach were a few houses, frail-built things, mostly covered with cotton cloth. Numbers of tents to be seen here and there. It was but a depot or landing place for provisions from which the miners on the Smith River could be supplied. Such was Crescent City. All goods were packed on mules over rugged mountains to the mines. There were no roads. No wagons had ever been seen there. No social life, no family ties found men here. It was gold. Greed for gold that brought hither the struggling crowd.

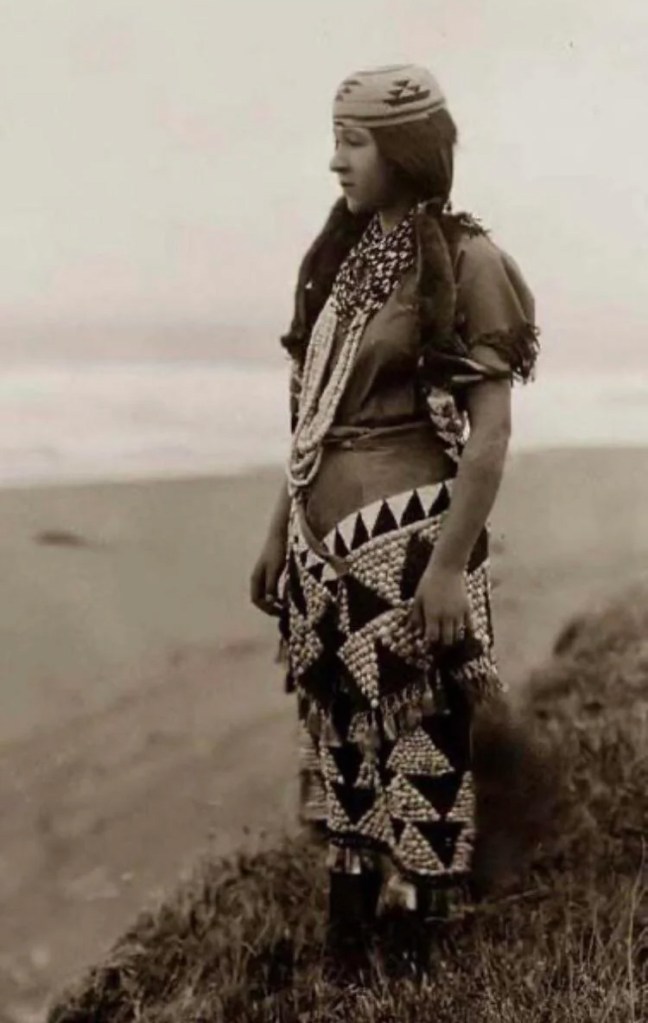

On arrival there, found many buildings going up and business rather “brisk.” On the bluff I speak of as forming the northern horn of the crescent, there lives a remnant of a tribe of Indians, probably thirty or more. They are friendly to the whites, mingle and go about town without any hesitation. They supply themselves with food and clothing by exchanging fish and clams.

There must have been a large number living here at one time, for there are the ruins of many homes. They built their houses much the same as those I wrote to you about before, only built-up boards up the sides and laid on the roof; the door or entrance is a round hole close to the ground about two feet in diameter with a large board sliding back and forth to close it with…

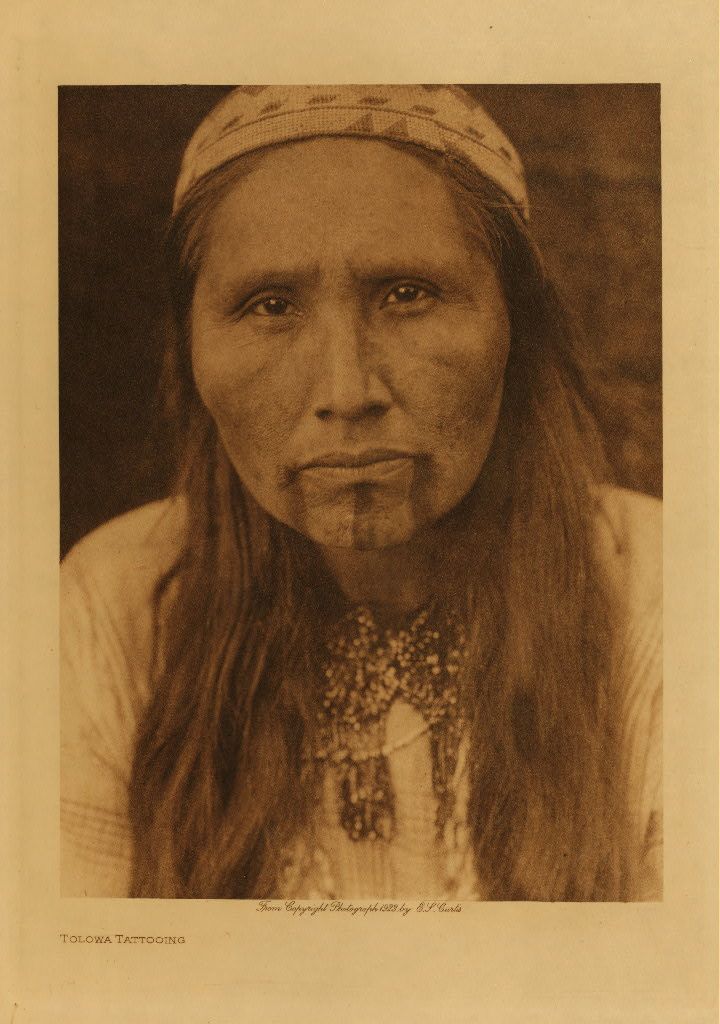

The females were all tattooed on the face with a dark line being drawn from the corner of their mouth and crossing up on their cheek. Also from the middle of the underlip down on the chin. This is done in youth and appears to be done to distinguish the different tribes, or rather families, that live about 10 or 15 miles apart. Each group is often called by a different name.

Nothing could be more primitive than their mode of cooking clams or fish, merely throwing them into the fire and roasting, or boiling them in baskets made of little twigs and made watertight with grass roots. The boiling was achieved by putting hot stones into the water in the basket. Clams and mussels are found and easily procured. They are cooked in this way. The spears appear to be the most ready way to take the fish, although they had nets, too. Immediately back from the south cove there was a swamp which appeared to be the bed of a river grown up with trees and bushes. The Indians gathered large quantities of berries, then into town trading them off for beads and accessories.

They dress in fox skin, although many of them get clothes from the whites. I saw many of their graves. They do not burn their dead, but bury them with all that belongs to them in the way of clothing, ornaments, etc. When a man dies, in his grave is laid all his weapons of war, and the paddles from his canoe and fishing tackle are laid upon the grave. A large board is laid over the grave covering it entirely.

At the head they put spears or sticks with which they dig clams according to the sex. I measured a board that covered a grave which was 3’6″ wide and 7′ long, perfectly clear and split out and made of redwood. There were some graves where I saw the baskets the women used to bring water in. Also they used to gather clams or put fish in. At the head of one of these graves I also found standing a stick which they used to dig clams with. It is 3 feet long and about 1½” in diameter and sharpened at both ends. This is stuck in the ground as a headstone.”

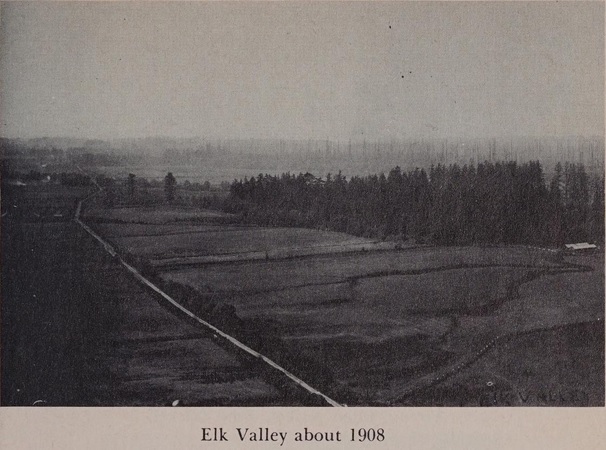

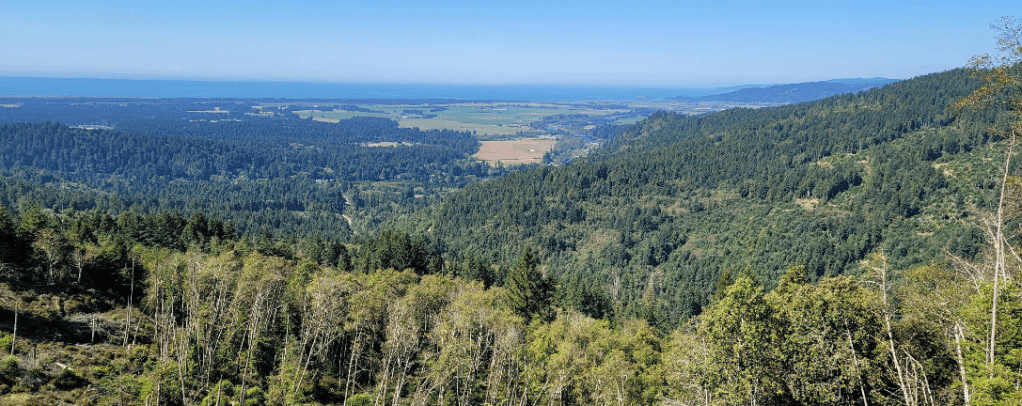

By 1853, Crescent City was set to become a major supplier of goods to the Illinois Valley and interior mining camps. A pack trail was established linking Crescent City with the Illinois Valley and Jacksonville. This pack trail, called the Cold Spring Mountain Pack Trail, was originally an Indian trail. It was improved by a party of men from Sailors’ Diggings, and by September 1852, the trail was good enough for packs animals. “On leaving Crescent City, this trail crossed Elk Valley, passed over Howland Hill, descended Mill Creek, crossed Smith River at Catching’s Ferry* (Bearss 1969),” and continued along the north bank of Smith River to present day Gasquet.

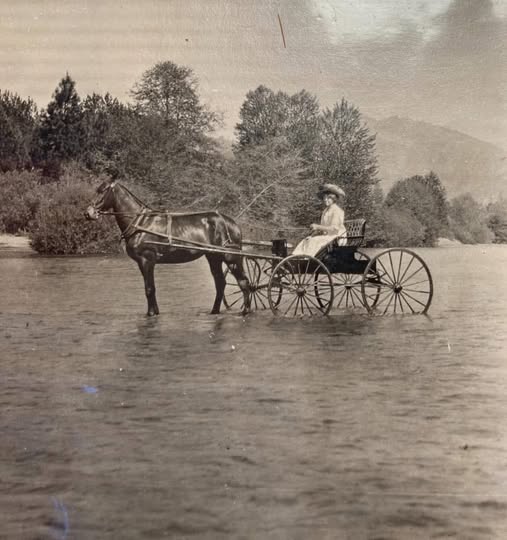

*Catching’s Ferry would not be established until the 1870s. Before then the river had to be forded in this vicinity.

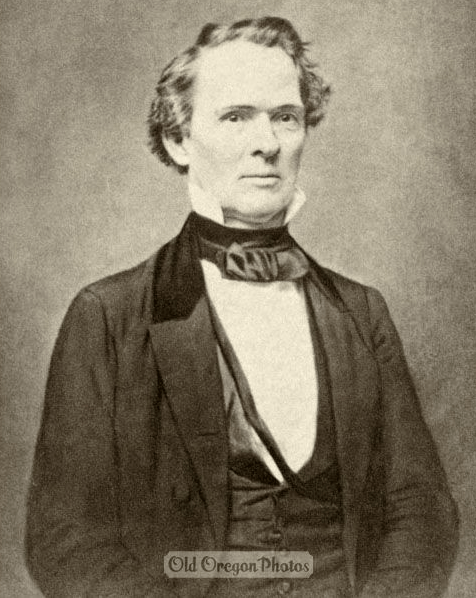

Stephen Palmer Blake:

The road for the first six miles lay in the valley which has the appearance of being that of a large river, it then turns off into the mountains. We left town in the afternoon and stopped for the night at the “mountain house,” so called because it is built where the road turns off to the mountain.

Elk Valley, an ancient, dried up route of the Smith River, was named after the massive herds of elk that were found grazing there.

Starting in the afternoon we proceeded a few miles out and came to the hills. Our blankets on the pack train had not arrived. We camped in a forest of redwoods not far from the only house we have seen since leaving Crescent City.

Much has been said about the redwoods, the large size. But I have noticed something I have not seen mentioned, which is that where the large trees grow there were no small ones. All large or all small. Sometimes we passed an open space of a half mile where there would be no trees, leaving a thick forest of very large ones and passing through open space, we encountered a forest of much smaller ones, nearly all of a uniform size. In the open spaces there were usually found serviceberry bushes which were then bearing fruit. They are a small blue berry and very sweet, rather unpleasant to me.

As soon as our train came in sight, two of us started on ahead and entered a very thick forest soon after leaving the house, mostly redwood. My companion was fresh from the eastern states and was much struck with the size and appearance of the trees.

Leaving our camp early in the morn, two of us going ahead of the party, we entered the heavy redwood through which the path led, and traveled on steadily, intending to make “Hardscrabble” before night. In the forest we entered, the trees were very large. We measured one 18 feet diameter and 100 feet to the lower limb. The branches were so closely united above that no sunshine reached the ground. It was silent and gloomy traveling through the forest. We sometimes passed a fallen monarch that was an immense size.

No living thing had been seen since our entering this gloomy place. We must have gone some miles when I heard a short crunching noise a little ahead and on our right. There must have been a large animal that broke a stick with his foot. We stopped nearby a very large tree and a moment after saw a very large black bear coming toward us and going to cross our path.

My companion had a double-barreled shotgun loaded with shot. I had a 6-inch Colt 5 shooter and a bowie knife with an 8″ blade. Had the trees been of a size we could have climbed, I should at once have climbed up the tree. But there were no trees that were less than 8 or 10 feet in diameter and the bear was coming on the lope and passed close to where we stood.

I thought I should set the example of climbing but it was impossible, so I set the example of backing up against the tree on the side opposite the bear. George followed beside me and with his gun prepared for action. I was only afraid he would fire at the animal which I knew would be useless with small shot. Neither would I do it with a heavy rifle, for if hit by a small shot he would have killed one or both of us before dying. I therefore said to him, “Don’t you fire at the bear. Sit quiet and let him pass. He will not molest us unless we wound him.”

I drew my weapons and held them prepared to use them only if we were attacked. I knew this much about bears than to attack one while on foot. On a steady gallop the animal came and passed within 10 feet of us, apparently unconscious of our being so near.

Before I could move or speak to prevent it, George leveled his gun which he retrieved and fired at him at a distance of 30 feet. With a savage growl he turned rapidly around several times as if to return and attack from behind, but not seeing from whence came the attack, he started off on his old course. It was well he did not see us. We were well satisfied to let him go.

Nothing worthy of note transpired during our journey up to the “picking” unless it be crossing the mountain, when arrived at the top and while traveling on the backbone for two miles or more there was the most beautiful view as far as the eye can reach. Even to the Pacific. In cloudy weather the travelers were enveloped in the clouds and hurried on.

On the east side of the mountain the trail goes directly down to the Smith River. It is down, down, no foot of level land. Drop a rock from the mountainside or a small stone and it goes leaping and bounding until it reaches the river. To get out off the trail and miss your foothold would be death. The mountain is too steep to travel on only by holding onto the bushes

The merchants in Crescent City hired men at $90 per month and had the trail built on the east side of the mountain. They dug it out and fixed it so that a mule train could travel. It is the most tiresome road I have ever traveled. I could hardly keep from going at full run down. It was so steep that it made my knees ache bracing back.

Arrived at the river; there is a small place just where a small creek forms a junction with Smith River. There is a round tent with its store, tavern and place of general resort for all the miners. A few bags of flour, a half dozen hens, a few pieces of pork, a bag of beans, a half dozen picks and shovels, four or five kegs, a few shirts and socks, and you have the contents of this store.

I read the mining laws which were posted on the center pole of the tent. The miners met in a mass meeting, framed and passed it. The next man I saw was an old friend and shipmate. He did not give me a good account of the mines. He advised me to prospect it myself. I did so. I found gold, but it was very fine. A few miners were making $5 to $8 a day. Many had put in wing dams and had left, their claims not proving good. I put blankets on my back, some bread and raw pork, and three of us went out prospecting. We found gold most anywhere but not in sufficient quantity to work.

From there, the trail climbed Elk Camp Ridge to Cold Spring Mountain, then north along the ridge to Oregon Mountain, over it and down to the Illinois Valley to Sailor Diggings. (Ruffel 1995).

Next day started earlier and addressed ourselves to a hard day’s walk, having the mountain to cross called “Four Mile Mountain.” It is by far the worst I have ever been up and we were obliged to stop every few hundred yards.

It is well wooded with pine and cedar on the west side, but the east side is nearly barren. Some years ago fire burned over the east side, and hardly a green bush or tree is to be seen. Whole forests of large pines stand dead and charred.

It was a hot day, calm and still. We had no water from the time we left the river until we reached the west side of the mountain, a mile or more from the summit, where there is a spring called “Cold Spring.”

And well does it deserve the name. I never drank as cold water from a spring as I did from that.

We were very thirsty when we reached the spring. A glass of cold water was more valuable to us than a bottle of whiskey or a pound of gold. Water only would quench our thirst. The spring is small, not over 2½ feet in diameter, between two large rocks and approximately two feet deep.

The rocks surround it so that it is a kind of basin. The water rises and flows gently over the top running in a riddle down the mountainside, where it is then drunk up by the parched earth.

We stopped there some little time to rest and refresh ourselves with the cold water. We bathed our heads and washed our feet. There was no shade there, only what could be had from the bodies of several large pines that stood beside the spring. They were dead, black and charred by fire.

As we left the spring, rested travelers, the trail led down the mountain. The descent was gradual and a good trail. We reached “Elk Camp” in good time.

We had a good trail the day following, for a mountain trail. The country was well washed with pine, ash and cedar. The redwoods do not extend so far inland.

Our course has been east, northeast most of the time. The day was very warm but water was plenty, passed many little streams and crossed rivers. Reached a house in time for dinner. There we saw the first woman we had seen since we left Crescent City.

The McGrew Trail may be the most intact of all the old mule trails. Unfortunately the forest surrounding it was devastated by wildfire 25 years ago.

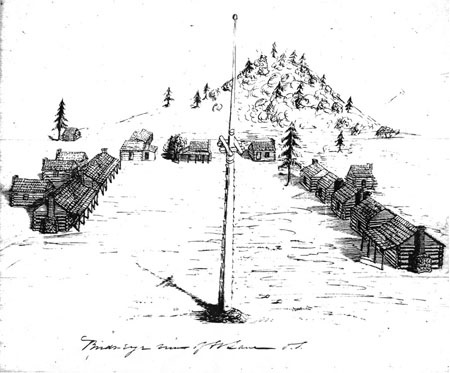

During the afternoon passed through the “Sailors Diggins.” There diggins are extensive and are what the miners term surface diggings. The gold is very fine and lays there in or on top of the ground. At the time we passed through there they were entirely deserted, being no water to work with. We passed very good log cabins on the road, and the surrounding hills were spotted with them here and there.

.

The country in and about the diggings is open and the hills low and rolling. There is some timber nearby and a few miles off an abundance of heavy pines. The earth is of a dark red mixed with broken stone of a dark reddish color. There was one house in the diggings inhabited and kept as a tavern. An attempt has been made to cut a race to bring water from a river nearly “18 miles” into the diggings but failed after partly finishing it. It can and will be done some day.

We reached Cochran’s Ranch just before night, tired and footsore. My boots were not tight and the dust and small gravel got into them and made my feet very sore. Cochran’s Ranch is situated immediately at the foot of “Democratic Gulch” where some few mines are doing well. The gold is coarse and rather dry. There too many have left for lack of water.

About three miles from the ranch are the diggings at “Althouse Creek.” They are extensive. I know but little of them. I washed my feet at every opportunity and when blistered and chapped I found it did them much good.

We left in the morning after an early breakfast and took a new trail which was said to be shorter than the old one.

After traveling three miles we passed Hay’s Ranch; one mile further we passed Johnson Ranch. I learned this from a little girl that was playing in front of the house. Soon after, we crossed quite a large flat and then entered a thick forest of pine and various other kinds of wood. We passed around the foot of a high mountain, and once several low spurs all covered with heavy pine and thick underwood. After traveling until about midday, came to Mooney’s Ranch, a house in the woods, solitary and lonesome; here we found the prospectors of the house both alone. Two others had gone out to bring in provisions.

The deer and all kinds of game are more plentiful about here than any place we have passed except perhaps Crescent City where people live on game. Mr. Mooney told me that they got deer and bears whenever they wanted them. The trail was full of deer, bear and wolf tracks. We also saw grouse and hares.

After about four miles, we came to a steep little mountain, the trail going directly over it.

After traveling about 16 miles it became too hard for us to climb this mountain. It was steep and the trail full of rolling stones so it was difficult to go up two feet and not slide back one.

Before we got to the top, we met two young men coming down with mules. They had dismounted and were leading them down.

These two travelers were the only ones we met for more than 45 miles. After reaching the top of the mountain, we took a short rest and went on the trail that went along the back of the mountain some little distance, and then the descent was gradual, with mountains looking off a long distance, at the foot of it a small creek. There I saw a small bunch of muskflowers the same as those I saw on the Smith River.

When we came into the valley I found wild cherries, ripe, and quite a treat they were. They were the first I had ever seen in this state. They were rather large, black, and grew on bushes about eight feet high.

We crossed some rolling hills covered in places with manzanita bushes. The berries were just getting ripe. We stopped. My companion laid down with the gun beside him while I went off a short distance to gather some manzanita berries. They are nearly all seeds and have a sour taste. My companion told me not to go too far off. I picked my hat full of berries and went back and found my friend singing.

This day, all along the road saw Indian tracks and heard their shouting on the mountain. It trailed about ten miles when we heard the crack of a rifle on the side of the mountain on our left and shortly after two loud yells. We kept on, taking no notice, thinking it was Indians. Crossed Applegate Creek and took a trail up the north bank. Saw two Indians with rifles near the trail. They went up the side of the mountain and we did not see them afterwards.

We had now come to where there was mining going on down the creek. Passed log cabins, wing dams and mining claims deserted. Came to where some Indians had been fishing for salmon.

Saw an old man, unarmed. He came into the road and stood still without speaking My companion could talk jargon, a kind of a language understood by nearly all the Northern Californian and Oregon Indians, altogether different from their native tongue. We asked him how far it was to a house. The old man told him it was a short distance and that there were many white men there. I saw a small boy with a bow and arrow and a little child lying on a wing dam on the opposite side of the creek. The others had probably hid when they saw us coming.

We had now reached Applegate Valley and soon after came to a log house, and a little further there were more. We stopped at one that appeared to be the principal one, for there was quite a crowd collected there. They were all armed and appeared to be earnestly talking over some important matters. We soon learned it. The Indians had commenced war against the whites. Their first attack had been near Jacksonville. And at the time it was made, all the Indian villages had been deserted and they took to the mountains. This looked suspicious, and the miners collected together to investigate the matter. A few Indians that lived with the whites still lingered about the settlement. They dared not come boldly out and mingle with the white men, yet they left not because they were hostile towards them, but feared they might be killed.

We had found that all the villages below were deserted before the Indians attacked Jacksonville. This looked as if they knew the attack was meditated and left in time to secure safety for the women and children. The fact of the Applegate Indians leaving their houses and going into the mountains does not prove that they commenced hostilities. They knew the white men too well to think themselves safe there. There is no doubt but they were aware that the Rogue River Indians were about to take up arms against the whites. But it remains to be proved that they were concerned [i.e., involved] too.

We arrived at the valley at about 10:30 a.m., and I can assure you we were hungry and tired, having traveled 45 miles without anything except the berries. It was not safe for us to go on to Jacksonville, ten miles. And as a party was going the next morning we concluded to go on with them. It was voted by the miners and settlers there that the next morning a committee of four should go to the Applegate Indians and ask them if they wished for war. If not, to tell them to come and live in the valley near the whites, for if they stayed out they would be considered as hostile and be attacked by the first party that would find them.

The committee were to take an Indian with them that had long lived with the whites and could talk English. There was one that took an active part. He was known by the familiar name of “Old Grizzly.” He was tall and straight as a candle; his hair and beard were nearly white, hence the name. His beard was long and flowing, reaching down on his breast. I thought his ideas with respect to the way to act were good, yet he was strongly opposed by some who “went in” for killing all the Indians.

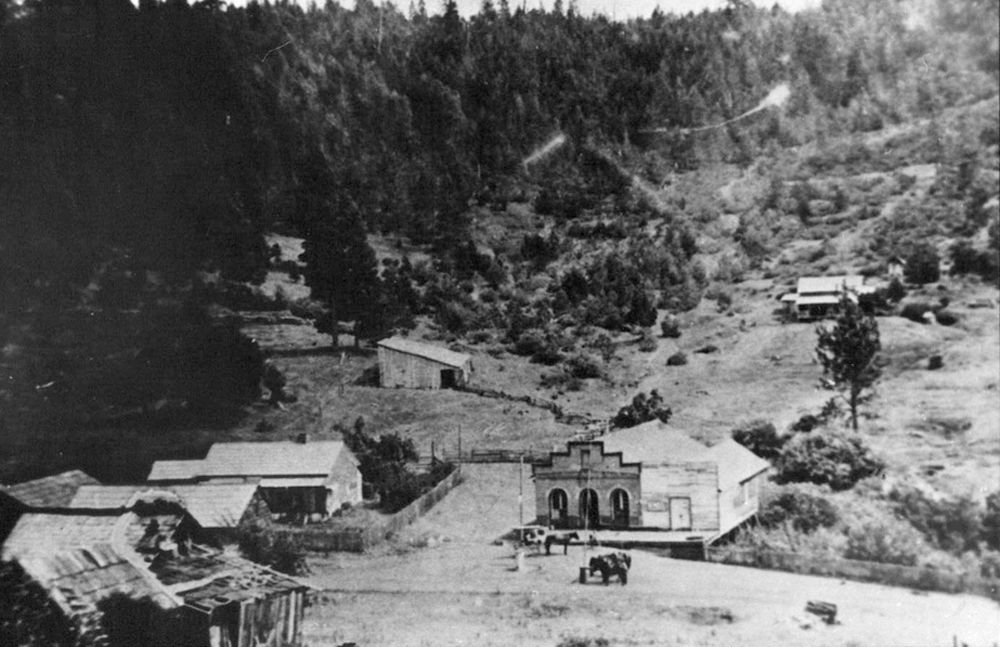

On the following morning we started for Jacksonville. The party consisted of 10 persons, mostly well armed. We passed on the road dead horses that had been shot by the Indians. Arrived at Jacksonville and found the town in a state of alarm. The Indians had all gone to their strongholds in the mountains, killing, burning and destroying as they went. Many settlers lived in the valley; some had their families. They too were alarmed and took their wives to Jacksonville. Some that lived at a distance of 15 or 20 miles from town met at their neighbors’ houses and fortified them. There they took their families and made a stand.

I should have stated before that the town of Jacksonville was on the Rogue River in the Oregon Territory, near the rolling hills on the southwest side; and situated in the immediate vicinity are rich dry diggings. The trail from there to Crescent City makes it easy communication with San Francisco. There are nearly a thousand miles on this trail packing from Crescent City to Jacksonville and Yreka.

John E. Smith:

In 1853 the Rogue River war broke out and many settlers were killed by the Indians.

In the following report, Indian Agent S.H. Culver blames much of the initial conflict on the bands of Shasta Indians who were not residents of the Rogue River region, but were transient actors upon the territory of the Takelma, Modoc, Pi-ute et al.

S. H. Culver, July 20th 1854:

I entered upon the discharge of my duties as Indian agent for this district on the first day of August 1853 and arrived at this place on the fourth day of September following. …there had been a general war between the whites and Indians since the fourth of August… in which the lives of many of both parties had been sacrificed and a large amount of property destroyed… The feeling of hostility displayed by each party it would be almost impossible to realize, except from personal observation…

The number of Indians in this district is not large; it is as follows: …men 180, women 199, children 158. The foregoing are the Indians that properly belong in what is known as the Rogue River Valley, though about one-quarter may be added to cover the number of transient Indians generally in the country. Sometimes the number of non-residents is probably greater than the one-fourth mentioned, at other times less.

I have ascertained that these transient Indians have been, and still are, in the habit of taking advantage of the bad repute in which those belonging here are held, to come into their country for the purpose of committing depredations, which are charged to those permanently residing here, for generally the settlers are not aware of the fact even that strange Indians are or have been in their midst.

At the present time there is a party of Shasta Indians in the mountains, not more than thirty miles from this agency, who belong in California. They have already stolen five horses, and before they can be found and hunted out may steal and destroy much more.

These parties are very liable to involve the Indians that properly belong in this country in difficulties, and it is doubtless their intention to do so now, as they have done formerly, that they may plunder and murder during the general misunderstanding, but so far this season they have not been able to accomplish their purpose. On all such occasions I spare no necessary trouble or expense to ascertain who the authors of the depredations are, and prevent them from making a difficulty general.

Up to the present time much the largest portion of the outrages committed upon the whites have been the work of these migrating bands of ungovernable Indians. It was by such a party that the war in this valley last summer was caused; from the want of correct information of the real authors of the outrages done them, our citizens prosecuted a vigorous warfare against the Indians of this valley for depredations in the commission of which they bore no part. The Indians were compelled reluctantly, as I am informed, to take up arms in self-defense, and were even ignorant at first of the reasons why they were pursued; while our own people supposed themselves also to be prosecuting a defensive war…

It was and is now a general belief among settlers in the valley that a war with the Indians here this summer is inevitable; and on two or three occasions it appeared as though such a calamity was indeed near at hand, but by prompt attention, aided by the generous forbearance of our citizens, and when necessary the immediate and vigorous assistance given by Capt. A. J. Smith, commanding officer at Fort Lane, peace has so far been preserved.

The food of the Indians consist of deer, elk and bear meat, with fish of several kinds, principally salmon, and a great variety of roots They cannot supply themselves by the chase for want of ammunition, as there is a territorial statute prohibiting the sale of it to them, and were it otherwise it would not be prudent to give them much at this time.

They take more or less salmon during five months in the year; formerly they subsisted in the main upon roots, of which there was a great variety and quantity; each kind had its locality and time of ripening or becoming fit for use, but the whites have nearly destroyed this kind of food by plowing the ground and crowding the Indians from localities where it once could be procured.

They did not find these roots upon any one tract of country, but there would be an abundance in one locality one month and of another variety at another place during the ensuing year. The settlers have interfered, by the cultivation of the soil in the valleys with the obtaining of this species of food to such an extent that while they can get plenty during certain seasons of the year, they will at other times be in a starving condition.

Under these circumstances it was deemed necessary to anticipate the ratification of the treaty and put in a crop of potatoes sufficient to prevent them from suffering, and perhaps starving, the coming winter; also on account of the influence it would have in keeping them under control during the summer. Humanity, too, seemed to require it, for our people had taken from them their means of subsistence, and ought at least in return to see that they did not starve before they received an equivalent for the territory relinquished by them, for, as they say, promises do not stop hunger.

Unless a crop was put in the past spring, of course it could not be done until the next, which would allow more than two years to elapse from the date of the treaty of purchase until they realized an equivalent in the way of provisions, unless obtained sooner for them by purchase, and the annuity is not sufficient even to keep them alive if invested in that manner.

The chiefs urged it and said [that] although they would like clothes and blankets for their comfort, yet something upon which life could be sustained ought first to be looked to; and further they urged that it was a thing impossible to control their people with certain famine staring them in the face.

They express a willingness to try to imitate the whites, and raise something to sustain themselves whenever the means for so doing is furnished them, and to do all in their power to induce their people to do the same; and I have strong hopes that nearly all can be persuaded to do so.

The Shastas and other associated tribes had signed a treaty in November of 1851. They agreed to give up their territory in the Scott and Shasta valleys, with the exception of a 30 mile stretch of land in the Scott Valley that would be set aside as a reservation for the tribe. The conditions of the treaty also stipulated the government would supply the tribes with food for 2 years while they began the process of cultivating the reservation lands.

However, unbeknownst to the tribes, the US Senate had rejected 18 California treaties in July of 1852, after too many settlers had objected to losing access to the reservation lands. The Senate then resolved that the rejected treaties be “filed under an injunction of secrecy.” This meant that for over 50 years, whenever California tribes or their advocates asked about the treaties, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the War Department denied all knowledge of their existence.

The Shastas, who had been promised farming assistance and supplies of flour and cattle, continued to starve while waiting for fulfillment of what they thought was a done deal. As far as the official word from the United States was concerned, there was no deal, and never had been. By 1853 the Shastas, who “belonged in California”, had no land to call their own, and no understanding of why the government had turned its back on them. So they roamed the lands, looking for sustenance wherever it could be found, “transient” and “ungovernable”. This displacement would prove disastrous to tribes like the Modoc.

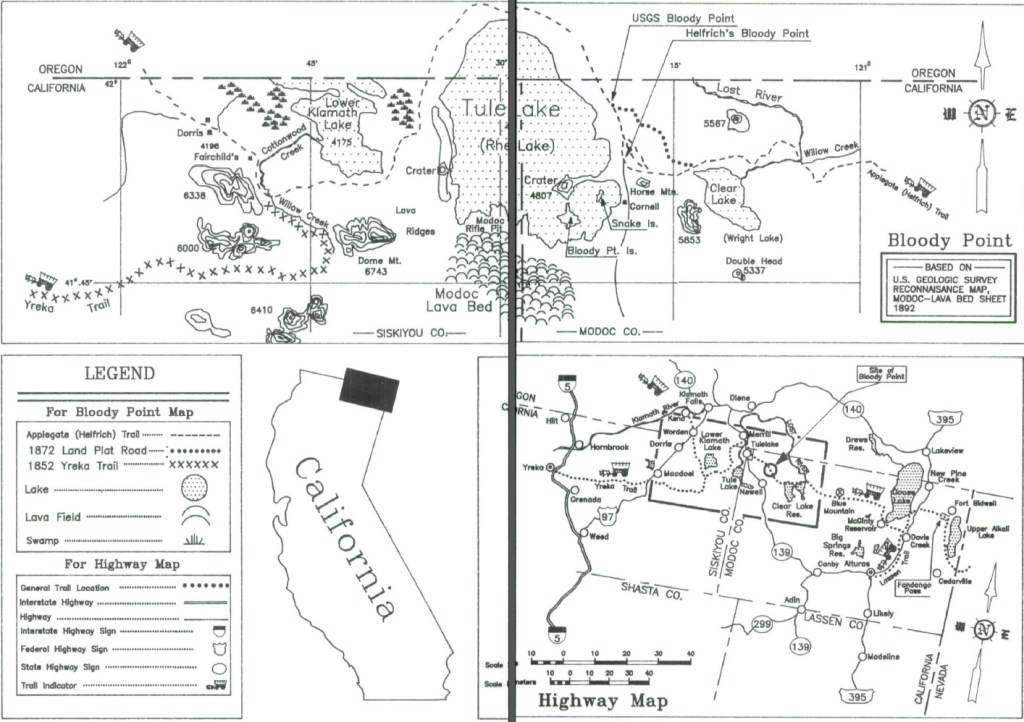

The ancestral home of the Modoc Nation… consisted of over 5,000 square miles along what is now the California-Oregon border. On the west loomed the perennially snow-capped peaks of the majestic Cascade Mountains; to the east was a barren wasteland of alkali flats scaling to the peaks of the Warner Mountains in the Sierra-Nevada range; towering forests of Ponderosa pines and shores of majestic bodies of water and rivers were to the north, while the Lava Beds … and the Medicine Lake volcano range to Mount Shasta formed their southern boundary.

The Modoc were hunters, fishermen, and gatherers who followed the seasons and managed the landscape for food and developed products to be used with their keen sense of economic trade. The arrival of the white European Americans in the early 19th century changed their lives forever.

The intrusion of exploring fur traders, and then Euro-American settlers, into the Pacific Northwest had a variety of social and economic effects on the Native populations. The Modoc bartered with fur traders for guns and horses, which became necessary to remain competitive with neighboring tribes. But… later settlement and individuals focused on seizing land for profit had little regard for the Native inhabitants. These new American invaders traveled west by way of the Oregon Trail, which passed directly through traditional Modoc lands.

The Modoc chose to live peacefully with the farming and ranching newcomers, often working for them and trading for livestock and other necessities. The flow of non-Indians into their ancestral homelands had an enormous effect on the culture of the Modoc people. They embraced many of the settler’s ways, and eventually began to wear clothing patterned after non-Indians with whom they socialized in the town of Yreka, California…

As more and more settlers arrived each year, more and more lands were deemed to be needed to farm and to graze. This influx of settlement amplified the misguided motivation to remove the Modoc from their homelands and was perpetuated by the 1849 Gold Rush and California becoming a State in 1850.

<In January of 1851> California’s first Governor, Peter Burnett, declared that it was necessary for a policy to support a “War of Extermination” to be waged upon the Indians until their “race becomes extinct;” the California State Legislature appropriated a half-million to pay for militia campaigns to kill the native people of California.

In 1852 a self-proclaimed “Indian Fighter” by the name of Ben Wright took advantage of the California State policy that sanctioned and funded the killing of Indians to raise an army of miners in the town of Yreka. This group set off to find any Modocs they could find, because it was rumored that they were the Indians who had allegedly attacked a wagon train of settlers.

Over a one-year period, the Ben Wright led militias ruthlessly killed an estimated 170 (or more) Modoc Indians of all genders and ages in a California state-sponsored genocide. His largest campaign was in the fall of 1852 at the mouth of the Lost River along the Oregon-California border where he killed as many Modocs as he could under a white flag of peace.

…Early in the summer of 1852, John Onsby received a letter at Yreka, by way of Sacramento, from an uncle, stating that he and many others were coming on the old Oregon trail to Yreka, and that great suffering would ensue if they were not met by a supply of provisions. This was the first emigration into Yreka by this route, and as the character of the Modoc Indian was well understood, it was thought necessary to send armed protection as well as provisions….

A company was raised in a few minutes, a large quantity of supplies were contributed and then the question was asked who would take charge of the expedition? At this juncture Charles McDermit, the recently-elected sheriff, stepped forward and offered his services which were gladly accepted. As hastily as possible preparations were completed and the expedition started in the direction of Lost River.

The first train of emigrants they encountered before reaching the Modoc country, and they hastened on. After passing Tule Lake they met a party of eight or nine men who had packed across the plains. McDermit and his company went on and the packers continued towards Yreka. When they [the packers] reached Bloody Point they were suddenly attacked by the Modocs. All were killed save one named Coffin who cut the pack from one of his animals, charged through the savages and made his escape.

Bloody Point is a place on the north bank of Tule Lake, where a spur of the mountains runs down close to the lake shore. Around this the old emigrant road passed, just beyond being a large open flat covered with tules, wild rye and grass. This was a favorite place for ambuscade.

When Coffin arrived in Yreka with the news of the massacre the excitement and horror were great. Ben Wright was sent for, and a volunteer company of 27 men was quickly organized and bountifully supplied with arms, horses and provisions by the benevolent citizens of Yreka. …

The next day and for several days thereafter, search was made for remains of the Modoc’s victims. Scattered about in the tules they found the mangled bodies of emigrants, whose death had not before been known. Two of these were women and one a child. They were mutilated and disfigured in the most horrible manner, causing even the strong-hearted men to turn away from the ghastly spectacle with a shudder. In reading of the massacre that occurred on Lost River a few months later [referring to Ben Wright’s killing of a large number of Modocs by treachery] this horrible sight must be kept in mind.

Here were found also portions of wagons, and the Indians were discovered to have in their possession firearms, clothing, camp utensils, money and a great variety of domestic articles, showing that some emigrant train had fallen a complete prey to the fiends. It was evident that a whole train of emigrants, how many no one could tell, had been murdered.

Twenty-two bodies were found and buried by Wright’s company and fourteen a few days later by a company of twenty-two men that went out from Jacksonville under Colonel John E. Ross. Of these last several were women and children, horribly mutilated and disfigured. Ross’ company remained but a few days and then returned to Jacksonville.

After burying the bodies found in the tules, Wright’s company escorted the large trains that had collected here as far as Lost River and went back on the trail to Clear Lake, where a camp was established. At this point scattered bands of emigrants were collected into large trains and sent on through the hostile country, occasionally having a little encounter with the savages, until, near the last of October, the last train had passed through in safety.

After remaining encamped on the peninsula for weeks, still being unable to coax the wary Indians to come close enough in sufficient numbers to make an attack on them worthwhile, Wright and his men moved up to the vicinity of the natural stone bridge on Lost River and camped near another Modoc village.

Wright had been warned by the Modoc mistress of one of his men that the Modocs were planning treachery, so he decided on some treachery of his own. He concealed his men at strategic spots around the neighboring Indian camp, marched into their camp alone early one morning with loaded guns concealed under the Mexican-style poncho he was wearing and issued a demand that the Indians surrender two white women they purportedly had captured. When they refused, he fired from under his poncho and killed the Indian to whom he had just issued his ultimatum. He then dropped flat on the ground. This was the signal for his men to open fire on the rest of the Modocs as they fled in great confusion. The Indians claimed that only five out of the 46 persons in camp escaped. … The whites then proceeded to scalp and mutilate their victims before returning in triumph to Yreka.

…The revelers took the town by storm; everything had to give way to them. They exhibited their hirsute trophies, flourished their weapons, and told what deeds of valor they had done, and what they would do to any one who doubted the story. No one durst oppose them, but when they became too violent and demonstrative, their weapons were coaxed from their hands, the bars of the saloon being decorated with them….

For a week one grand carousal was maintained by a majority of the members of Wright’s company and a host of their particular admirers, chiefly the riff-raff and scum of the town….

It would have been a more pleasant task to have related a different ending to this campaign, but this book deals in facts and facts are sometimes stubborn things.

Ben Wright was hailed as a hero in Yreka, where he paraded scalps, but this act of treachery radicalized the tribes. It directly set the stage for the Rogue River War skirmishes that began in 1853.

The “exterminationist” movement represented by those like Wright began gaining significant traction at this time. Where the native tribes would traditionally seek a form of justice in reprisal when they would attack, trying to follow a “one of yours for one of mine” rule of combat that had existed in inter-tribal warfare for untold centuries, the settlers operated from a completely different mindset.

In the case of the exterminationists, it began with viewing their opponents as vermin rather than equal adversaries, and ended with driving them from the land, if not their eradication. This was no longer a conflict between warriors, it was one group trying to annihilate the other – men, women, and children.

The ensuing escalation of atrocities on both sides of the conflict is too gruesome to recap in full detail, although the first half of 1853 is relatively peaceful according to official records – at the very least, mass-slaughter free. But the steady trickle of settler deaths eventually added up to a few too many, and oral histories attest to the fact that retaliation against native tribes during this time was far more substantial than has been noted in the historical record.

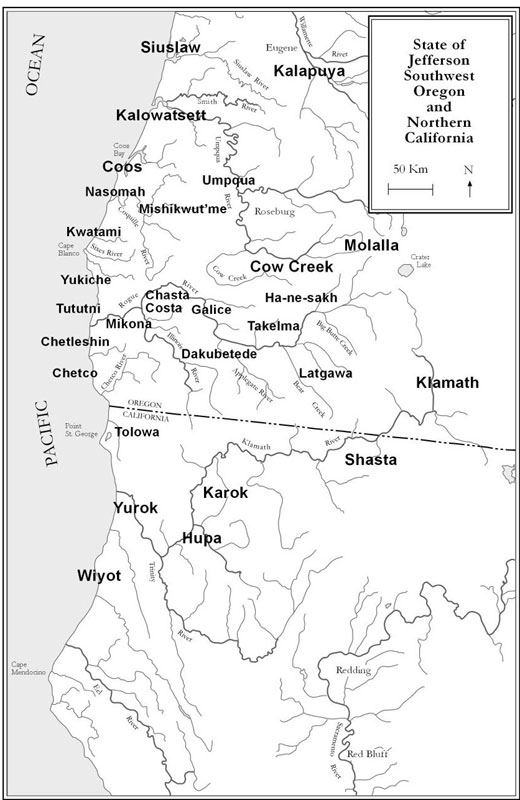

By the summer both sides could feel the simmering conflict about to boil over. Vigilante posses organized out of Crescent City escalated attacks against the Tolowa people; the historical record is vague but suggests that they carried out massive campaigns of slaughters against the tribe during their seasonal gatherings in both summer and winter of 1853. By the end of year somewhere between 150-600, perhaps even as many as 1000 Tolowa had been ruthlessly annihilated. The Tolowa were deeply intertwined with the tribes of the Rogue River Valley, such as the Takelma and the Shasta, and the coastal Rogue tribes. Their persecution reverberated throughout the region.

In the Spring of 1853 a man called California Jack accompanied by several others, started from Crescent City on a prospecting tour intending to visit some place near Smith’s River. A short time afterwards an Indian was seen in town carrying a revolver with the name “California Jack”, engraved upon it. Surmising that the prospectors had been murdered by Indians, a party of citizens attacked the Indians on Battery Point, near Town, killing the one who had the pistol and several others. A Company was immediately organized to search for the supposed murdered men. The camp of the prospectors on the banks of Smith’s River was easily found, and further search resulted in the discovery of the bodies of the men, all bearing marks of violence by the Indians.

After the punishment of the Indians at Battery Point, a large number of the survivors removed to a rancheria near the mouth of Smith’s River, known as Yontocket Ranch. But the feeling in Crescent City against them was too intense to subside without a further punishment being administered. A company was formed, and procuring a guide who had some knowledge of the country, near the ranch, prepared for the attack on the Indians. Of the manner in which the attack was made, no authentic information can now be obtained. It is well known however, that the fight ended in a disastrous defeat to the savages, a large number being killed, while the whites escaped with little or no loss.

A ranch is a Native village, a name devised in Spanish California originally as “Rancheria,” but shortened to ranch. Bledsoe clearly hedges his narrative suggesting that the whites “escaped” this massacre. Histories like this appeared throughout the west, most of which took the settler side, glorified the actions of their brethren, sometimes beatifying their direct ancestors, and ignored the most salient parts of their extremely racist and genocidal acts, painting the settler militia as somehow the victims of a massacre of their own making.

Reed accessed oral histories of this massacre from Tolowa informants, from, Ed Richards, Sam Lopez, and Amelia Brown, and published by Richard Gould.

“Pyuwa of Enchwo [a Tolowa Village], who lived to be a very old man, one of very few … survivors… People were gathered for Needash (World Renewal) after fall harvest, at the center of the world at Yontocket. Indians from all over gathered to celebrate creation and give thanks to the creator.

On the third night of the ten night dance, whites came into the village in the early morning hours. They torched the redwood plank houses, and as the Indians attempted to escape through the round holes in the houses, the militia killed them. This village existed as the largest native settlement consisting of over thirty houses. The whites would cut off the heads of the Indians and throw them into the fire. They lined their horses on the slough and as the Indians sought refuge, they were gunned down.

One young Indian man ran out of the house with a “big elk hide” over his body, fought, and escaped to the slough. He stayed down there two or three hours: “All quiet down, and I could hear them people talking and laughing, I looked in the water, and the water was just red with blood, with people floating all over.” “The flames of our burning homes reached higher as even our babies were thrown to their deaths.”

The center of the world, Yontocket, burned for days and that’s how the place received the name “Burnt Ranch.” Roughly five hundred Indians died in this massacre.

The Nee-dash is the Tolowa world renewal or feather dance, which happens twice a year. Yontocket was the location the canoes landed when the tribe arrived on this coast likely thousands of years ago and a village on the south side of Smith River. It was common for all of the Athapaskan tribes in the area (Tututni, Tolowa, Chetko, Pistol River, and some Rogue River tribes) to attend the Center of the Tolowa World, Yontocket, at each solstice. This massacre then is likely the Summer Nee-dash at the Summer solstice in Summer 1853.

August 6, 1853

On Saturday, Mr. Rhodes Noland was shot dead in his cabin door within a mile of town. The citizens who had been previously preparing for a skirmish, upon receiving intelligence of his murder, immediately started out and in a short time returned with a captive “siwash tyee” [“Indian chief”], who was mustered to an oak tree and there “strung up.” During the day three others were hung beside the tyee.

The Rogue River War was commenced by Shasta Indians who had been driven from Shasta Valley. They killed a man, Rhodes Noland, within hearing of the center of the town on the road coming from Yreka Sat. night Aug. 2nd, ’53.

A meeting of the citizens were called that night. They slaughtered indiscriminating war on Rogue River or Shasta Indians, though of the latter there were but few, and so those most guilty suffered the least.

On the 7th of August, the miners captured two Shasta Indians, one on Jackson Creek, and the other on Applegate. These Indians were both in their war paint when caught. They were brought to Jacksonville and on examination it was found that the bullets belonging to one of their guns were the same size of the one with which Noland was killed. There were other facts and circumstances which tendered to identify them as the guilty parties. They were tried by a miners jury and hanged before 2 o’clock the same day. In my opinion they were justly punished.

One of the saddest and most inhuman acts of the whole war remains to be told. Late in the evening of the day those Indians were executed, a small innocent <native> boy about nine years old was brought to Jacksonville by three men from Butte Creek, with whom the boy had been living. The poor little boy on being discovered by the miners [was] taken to a place near where David Linn’s cabinet shop is now standing, and near where the scaffold where the two Indians were still hanging.

I mounted a log near by, and called the attention of the vast crowd to the solemnity of the act they were about to perpetrate. I called on them to punish the guilty, but to spare the life of the innocent child. While pleading at the top of my voice the crowd gathered around the hangman’s tree. Someone called out “what will you do with the boy.” I replied, I will take him to a hotel and feed him.

I went to him and took him by the hand and started up California Street when Martin Angel came up on horseback and without alighting commenced to harangue the mob against the murderous Indians. He said: “The war was raging all over Rogue River Valley, we have been fighting Indians all day; hang him, hang him; he will make a murderer when he is grown, and would hang you if he had a chance.”

The mob at once seized the boy and threw a rope around his neck, which I succeeded in cutting twice. I was violently thrown back… The excitement was so great that I found that my own life was in danger, and I had to withdraw. I told them his blood would be upon their heads. But the cry was “Exterminate the nits, and you’ll have no lice.” They swung him from a branch before my very eyes.

I turned away with a sad heart at this inhuman conduct towards the innocent child, against whom no crime was charged. No mob ever committed a more heartless murder than this.

The following petition was brought by Mr. Wilson, who resided near Willow Springs:

Fort Wagner, Aug. 8, 5 p.m.

The citizens of Rogue River Valley ask the citizens of Yreka, in the name of humanity, to assist in subjugating the Indians of this valley, who are daily and nightly murdering our citizens and killing our stock. Between 400 and 500 Indians are in the vicinity of Table Rock. The citizens are not sufficient in numbers to guard the different points at which the families have collected, and go to fight them. We are poorly armed, and ask your assistance in men and arms.

Three men, Messrs. Dunn, Griffin and Overbeck, were killed on the 7th, near Willow Springs, besides Messrs. Nolan and Wills, whose deaths had been previously reported. [Patrick Dunn, B. B. Griffin and Dr. A. B. Overbeck survived.]

Early reports stated they were killed because the scene was so violent, however, Patrick Dunn survived a severe wound to the shoulder, and Griffin and Dr. Overbeck also escaped. News of their “deaths” was a major source of shock and outrage for the militias to rally around.

On the 8th, at 2 o’clock, the Indians had attacked two houses–Mr. Miller’s and Mr. Stone’s. Mr. Wilson had not heard the consequences when he left. All the inhabitants were gathering together at Wagner’s and were about building a block fort for protection. Most of the families in the neighborhood were at Wagner’s, Hoxie’s and McCall’s, ten miles south of Jacksonville. The main body of the Indians were encamped at and about Table Rock. Their chief had sworn to have the valley back or die in the attempt.

A company consisting of about 15 U.S. soldiers from Fort Jones, and twenty or thirty volunteers from Yreka and Greenhorn, well supplied with arms and ammunition, left Yreka on the 8th for the scene of action, and another company of much greater numbers was to have left on the 9th. The whole country was in a state of excitement. The people have gathered together at various points for protection. The Herald says: “Let this be our last difficulty with the Indians in this part of the country. They have commenced the work of their own accord, and without just cause. Let our motto be extermination, and death to all opposition, white men or Indians.” – Herald of Freedom, Wilmington, Ohio, September 23, 1853.

When the ranger militia arrived they set about a policy of extermination that took these conflicts to a whole new level. On the California Coast, exterminations of whole tribes were occurring. Their Athapaskan friends and relatives in the Siskiyou Mountains heard these reports and were not going to give in to the terror of the militias. The Rogue River tribes (Takelmans) banded with the Athapaskans, Shastans, and Cow Creek Umpquas and formed a resistance to the terror being spread. Exterminations and attempts to genocide the whole race of Indians in Northern California and Southern Oregon continued into the later 1850s.

In 1853, the Oregon Territorial militia commanded by General Joseph Lane was fighting a series of battles in the Rogue River valley, the main battle at Evans Creek. They were fighting the bands of Chief Jo (Apserkahar) and the bands of Chiefs Sam (Toquahear), and Jim (Anachaarah) and other head men for the Rogue River. During the battles, many men on both sides were killed and wounded.

After a day of fighting both sides were exhausted and Chief Jo called for a cease fire and parlay with General Lane, because of his respect for the man. Word was passed that Chief Jo was sick of war and wanted peace. General Lane responded and walked into Chief Jo’s camp unarmed, finding out that there are over 200 Indian warriors, well more than his men. Negotiations took place a following day, September 8th 1853, in the shadow of Lower Table Rock.

The Council of Table Rock brought a temporary peace between Indigenous residents of the Rogue River Valley and the American settlers that had swarmed into the region after 1850. The site of the Council’s negotiations was on the north side of the Rogue River, near the southwestern base of the main portion of Lower Table Rock, within a small valley formed by the horseshoe-shaped Table Rock.

The 1853 Council of Table Rock negotiated two treaties. First was the peace treaty, on September 8 (which was never ratified), between representatives of Oregon Territory and the Takelma, Shasta, Dakubetede, and other Indigenous groups of the Rogue Valley, bringing a temporary respite to the conflict in southwestern Oregon between Native people and the ever-growing number of white settlers and miners. A second treaty, dated September 10, was a land-cession treaty (subsequently ratified by the federal government) that provided for a reservation and various services to the Native people in return for relinquishment of their title to much of southwestern Oregon. The treaty-making required translation back-and-forth from Takelman into Chinook Wawa (the Pacific Northwest’s trade jargon).

On September 10, 1853, Takelma leader Apserkahar (known as Chief Joe) and former Oregon Territorial Governor Joseph Lane faced each other. Lane’s fellow negotiators included recently federally appointed Oregon Superintendent of Indian Affairs Joel Palmer; U.S. Army Captain A. J. Smith; leader of the local settler militia Colonel John Ross; Lafayette Grover (later governor of the state); as well as interpreters Robert Metcalf and James Nesmith (later a U.S. senator) as translators of Chinook Wawa.

The group entered the Takelma camp unarmed, and the parlaying lasted for much of the day. Nesmith later wrote that the party came close to being ‘killed to a man” when news of the latest murder of an innocent Native angered the Takelma leaders.

The ratified Treaty of Table Rock established a reservation on the north side of the Rogue River, including important salmon-fishing sites on the river; the two Table Rocks; the extensive oak-and-pine-filled Sam’s Valley (named for Apserkarhar’s brother, Chief Sam); and the mountainous, heavily forested Sardine Creek and Evans Creek watersheds. The location of an eventual permanent reservation was not determined. The treaty also promised various goods and services that would enable the Indians to farm and ranch and agreed that the U.S. Army’s Fort Lane (established in late 1853 on the south side of the Rogue) would protect the reservation’s inhabitants from land-hungry whites.

Next time:

“In 1854, I joined a company of the Oregon Volunteer Militia made up at Jacksonville. The company was used as an escort to go out on the plains and meet settlers coming to Oregon by the Southern route. I worked in the Quartermaster’s Department and had charge of the freight outfit… We did everything then with pack animals.”

To be continued…

Leave a comment