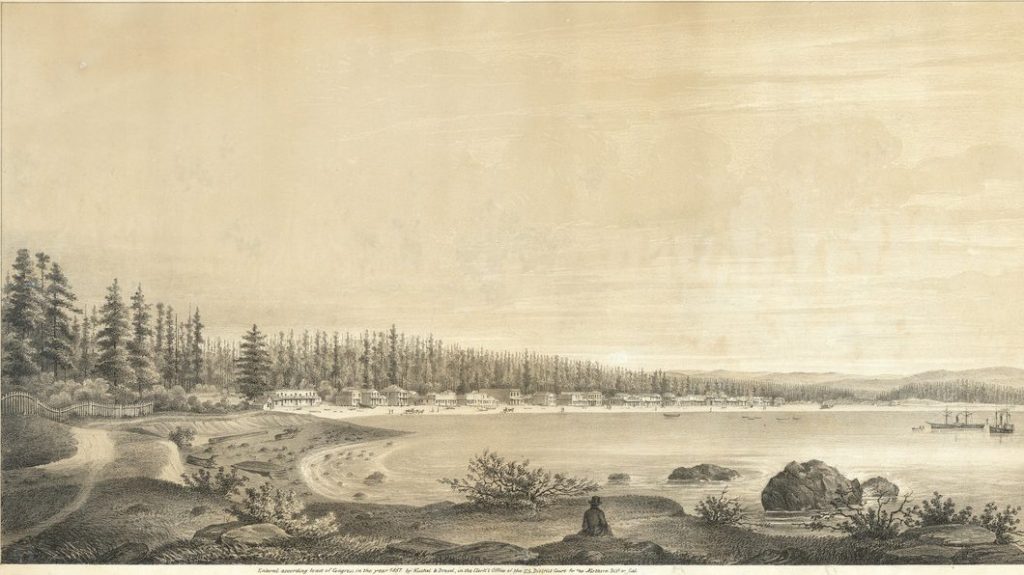

Previously: In 1852, 16-17 year-old Johnnie Smith went by boat from Humboldt Bay, California, to a mining town called Trinidad; then from there to Salmon River; from there to Scott’s River; from there to Yreka, California, on the Klamath River.

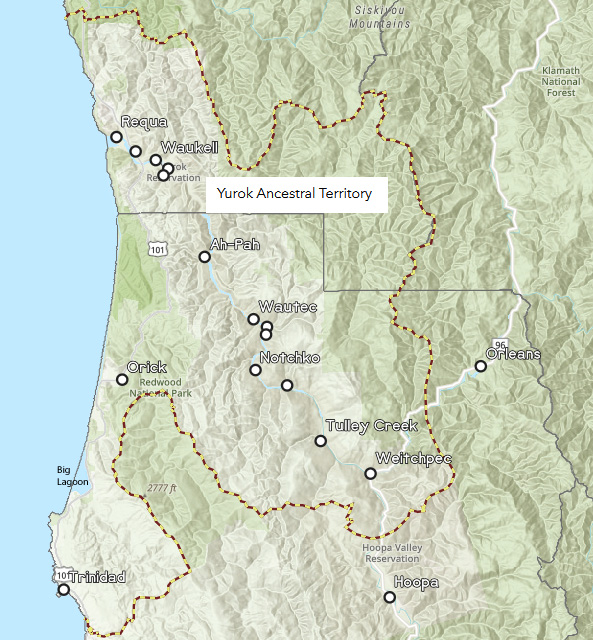

Trinidad was located in the southwestern lands of the Yurok tribe.

By 1849 settlers were quickly moving into Northern California because of the discovery of gold at Gold Bluffs and Orleans.

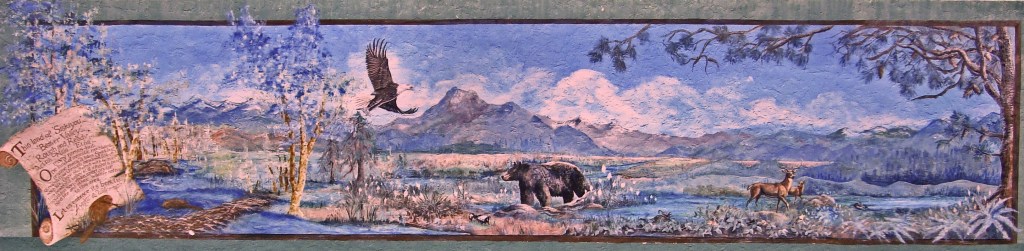

Yurok and settlers traded goods and Yurok assisted with transporting items via dugout canoe. However, this relationship quickly changed as more settlers moved into the area and demonstrated hostility toward Indian people. With the surge of settlers moving in the government was pressured to change laws to better protect the Yurok from loss of land and assault.

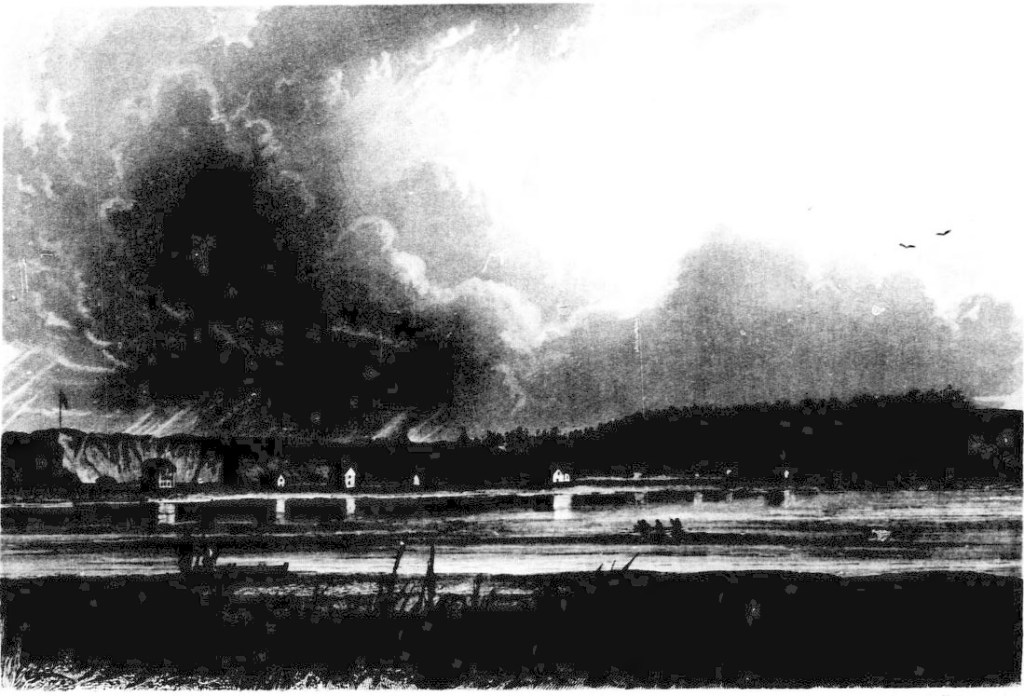

The rough terrain of the local area did not deter settlers in their pursuit of gold. They moved through the area and encountered camps of Indian people. Hostility from both sides caused much bloodshed… The gold mining expeditions resulted in the destruction of villages, loss of life, and a culture severely fragmented.

Edwin C. Bearss described the trails Smith would have taken from Trinidad to Yreka:

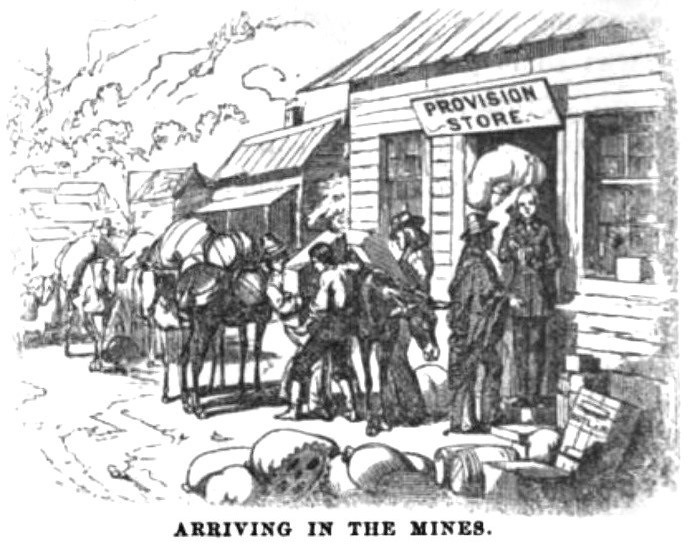

Within weeks after the establishment of the towns on the Humboldt Coast, trails were cut through the redwoods and across the mountains to the mining regions. Trinidad and Uniontown (Arcata) took the lead, as both were well situated by geography to act as supply stations for the diggings of the Klamath and Salmon River Districts.

Trinidad, the first town established on this reach of the coast, was for a few years the leader in the packing trade, because it was located closer to the Klamath diggings than the others.

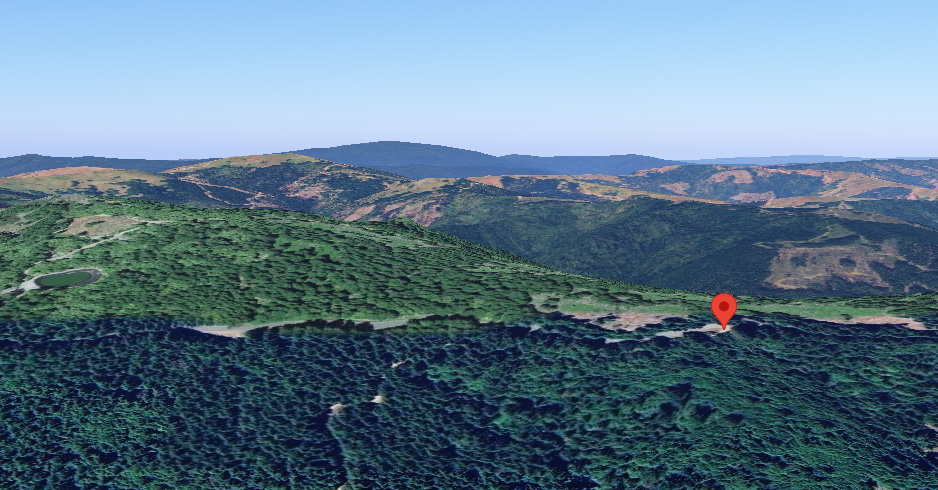

During the summer of 1850, the packers, utilizing old Indian trails, opened a route from Trinidad up the coast to Big Lagoon, then across the divide to Redwood Creek.

John Daggett was one of the adventurers who reached the Klamath diggings, in 1852, via the Trinidad trail. He recalled that from Trinidad they found it necessary to “furnish our own transportation, carrying blankets on our own backs,” as there were few if any inns on this route to the mining district.

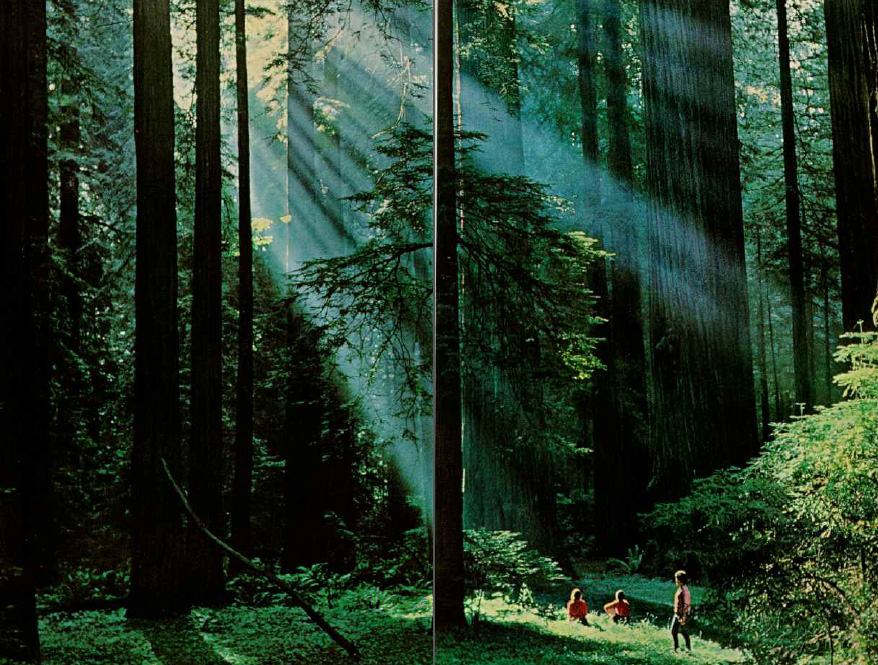

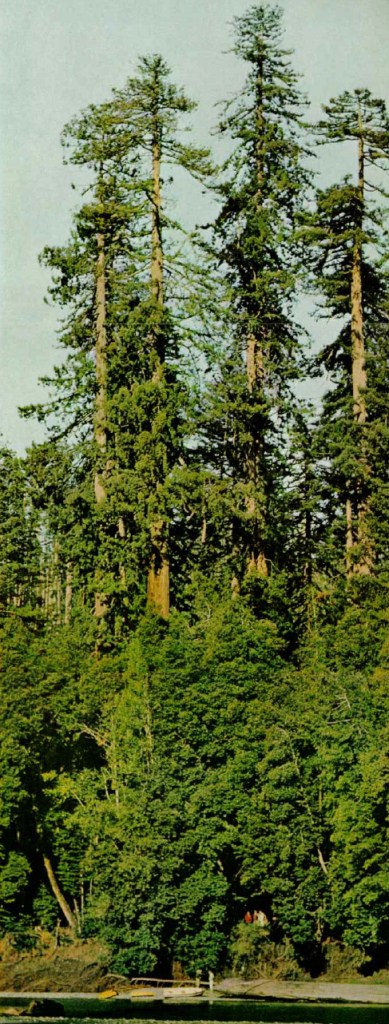

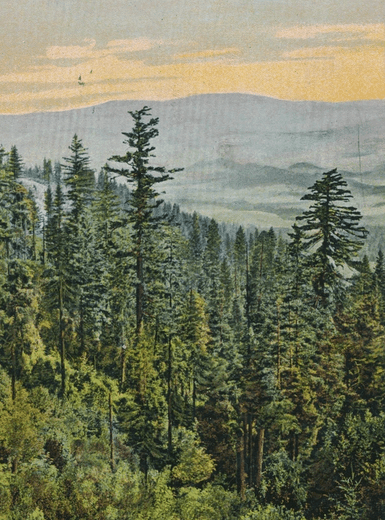

“We passed first through the grand belt of old redwood trees, a sight long to be remembered, thence over the bald-hill country, abounding at that time in elk.”

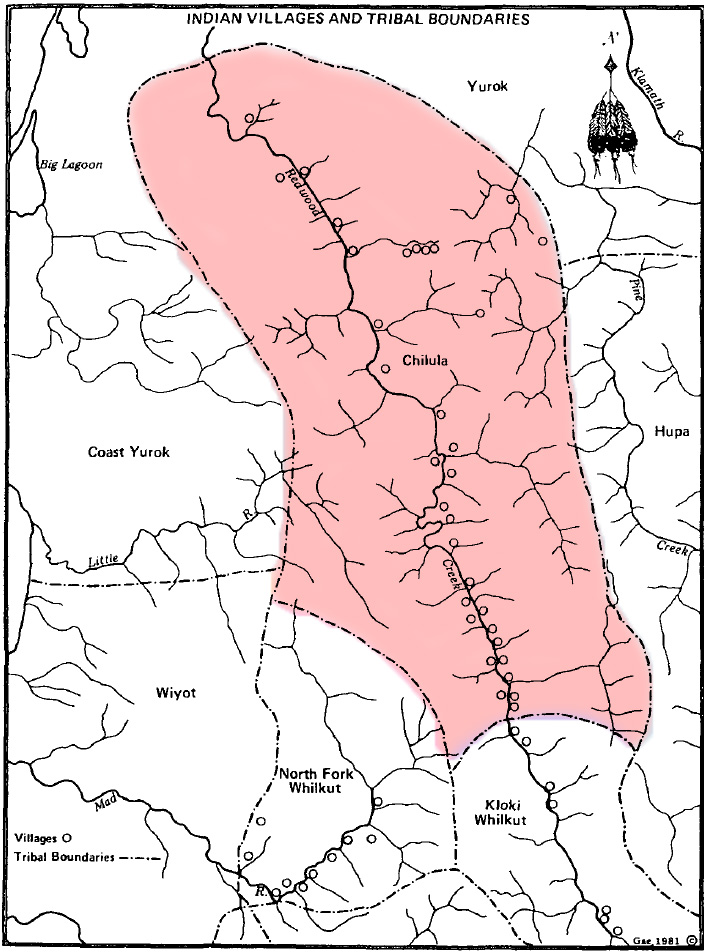

Redwood creek was the central artery of Chilula tribal lands.

California Indians – Chilula:

There were high hills along both sides of Redwood Creek in Chilula territory. On the western side, thick forests of redwood and oak trees came down to the creek. On the eastern side of the creek, the hills were broken by valleys with little streams running down them. It was here that the Chilula built their homes. There were more than 20 villages, with an average size of about 30 people.

These people who lived along Redwood Creek did not call themselves Chilula. This name was given to them later, and comes from a Yurok term, Tsulu-la, meaning people of Tsulu. Tsulu refers to the Bald Hills, the name given the hills in this area because there are no trees on the hill tops. The Chilula are also called the Bald Hills Indians.

Edwin C. Bearss:

Over 100 years before the team from the National Geographic Society in 1964 measured the Howard A. Libbey Tree and ascertained that it was the “world’s tallest tree,” packers and travelers on the Trinidad-Klamath Trail were aware of the great height of the redwood groves on Redwood Creek. As the trail crossed the stream close to the grove, the packers undoubtedly marveled at its size.

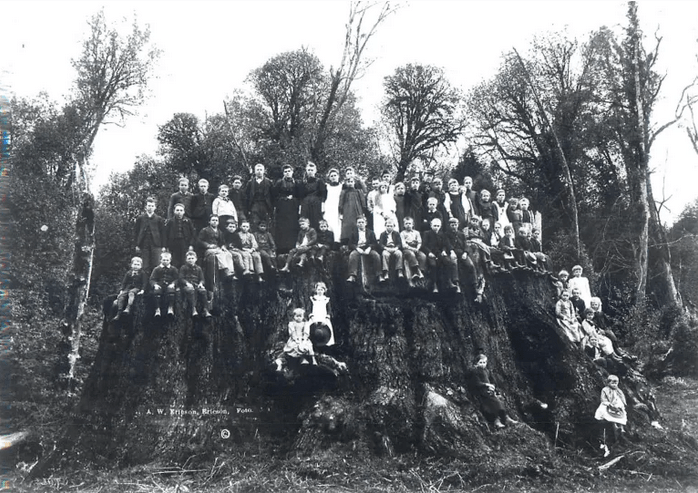

Mr. H. Vanderpool, in the late spring of 1853, wrote the editor of the Sacramento Daily Union that near Trinidad Bay there was “a magnificent redwood forest, in which there were a number of trees of very extraordinary size.” The largest of these trees was on Eel Creek and “measured 2 feet from its base, the almost incredible circumference of one hundred and twenty feet!”

“Eel Creek” must have been an early name for Redwood Creek.

A second tree on the Trinidad-Klamath Trail, between Elk and Redwood camps, which had fallen, “accommodated 17 persons and 19 cargoes or mule packs with abundant room for shelter for three weeks, during the rainy season of 1851.” A third tree in the same area measured 91 feet in circumference, one yard from its base, while a fourth, “which was prostrate, was from 70 to 80 feet in circumference, 291 feet in length,” with a portion of the top broken off in the fall.

Vanderpool championed these trees “as having no parallel for size in the known history of the world.”

While there must have been a little exaggeration to some of these claims, especially the entire pack mule train in the hollow of one tree, the documented existence of trees like the Fieldbrook Giant being felled 40 years later show how these trees could grow to be as enormous as the ones he described standing.

It is possible that a “goose pen” tree fell and was even further hollowed out. Goose pens are what results when a redwood tree is fire damaged and the inside of the tree burns, but the bark resists the fire and the tree remains standing. Settlers would often use these hollows as enclosures for geese and other animals.

Redwood Creek was forded at “Tall Trees,” and the trail ascended the Bald Hills to Elk Camp.

As more settlers traveled west in search of gold, many discovered the wealth of redwood trees or “red gold.” The wagon trails here were the forerunners to the logging roads that would crisscross this area in the coming years, leading to a major loss of biodiversity in the region.

Of the two million acres of old-growth coast redwood forest that once stretched from Southern Oregon all the way south to Big Sur, only four percent now remains. How fortunate we all are to be able to enjoy what has been left standing, preserved in perpetuity!” – NPS

It then passed along the crest of Bald Hills to French Camp, where the trail forked, one branch leading to the Klamath at Martins Ferry and the other into Hoopa Valley.

The Trinidad trail followed a route dictated by the topography, and intersected the route leading up the Klamath from Klamath City to Martins Ferry.

This part of the journey was through the south-eastern part of Yurok territory.

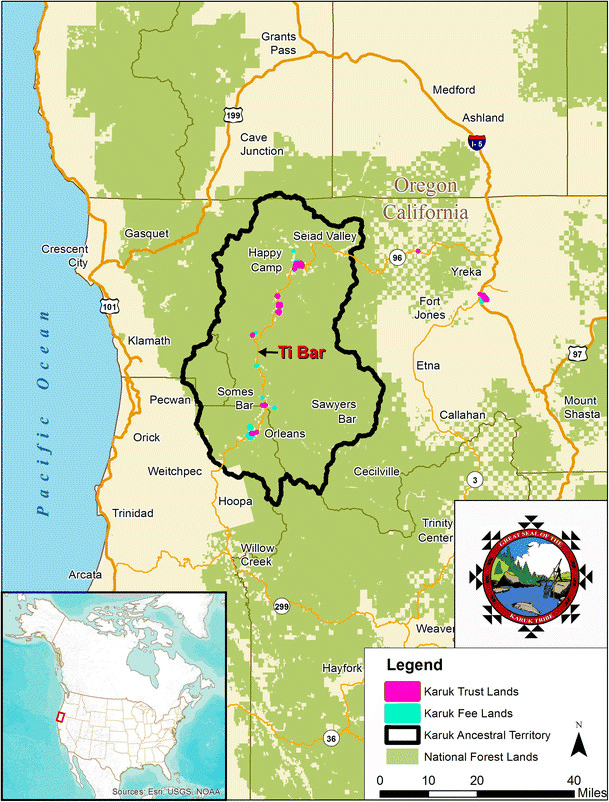

Past the village of Weitpec, the trail crossed over into Karuk territory as it headed north to Somes Bar, then went east from there.

Northern Humboldt Indians – Jerry Rohde:

The Karuks had lived in this area for countless generations, where the mountains rose in vast, forested diagonals and the salmon entered the river in great numbers.

Karuk villages were located next to the middle Klamath or lower Salmon rivers, giving them easy access to fish. The territory extended from the river to the top of the ridges, which were used for hunting, gathering, and ceremonial purposes…

The arrival of the Whites in 1850 marked a drastic change for the Karuk people and their land. Lured by the gold in the sand and gravel next to the river, white miners began washing the earth to find and take the gold. Their greed was all-consuming and they soon began to desire other things of value from the Karuks, including young Karuk women. This was the beginning of the Karuk genocide, as there was no legal or religious force to restrain the white invaders.

The miners’ actions disrupted the Karuk way of life, tearing apart the sacred pathways used by ceremonial leaders and filling the salmon spawning grounds with their tailings. They shot elk in great numbers to feed themselves, tromped on native trails with their pack trains, and drove off or killed any Karuk who contested their appropriation of the land. The miners also raped young Karuk women and sometimes forced them to live in their cabins.

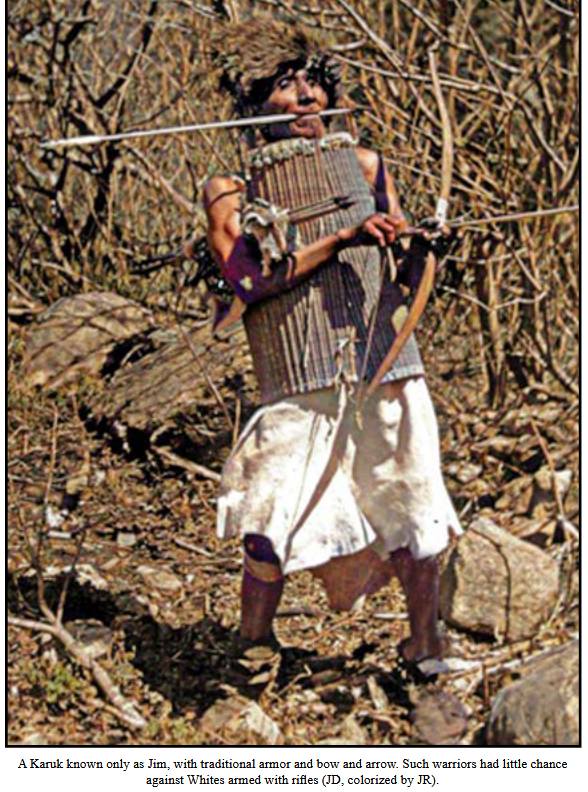

The Karuks resisted, but the Whites’ rifles made native bows and arrows almost useless. Due to the Karuks’ ongoing and justified hostility, many of the more fainthearted miners left, leaving only the “most energetic and daring” behind. Happy Camp was far from happy at all.

Ancestral Karuk territory had three main population centers. Farthest upriver was the area near Clear Creek, close to what would become the white mining town of Happy Camp. The next was around the mouth of the Salmon River, which included Katimîin, the Karuks’ “most sacred village”. The third was the vicinity around Panaminik, which was later replaced by the town of Orleans after being overrun by White miners in the early 1850s.

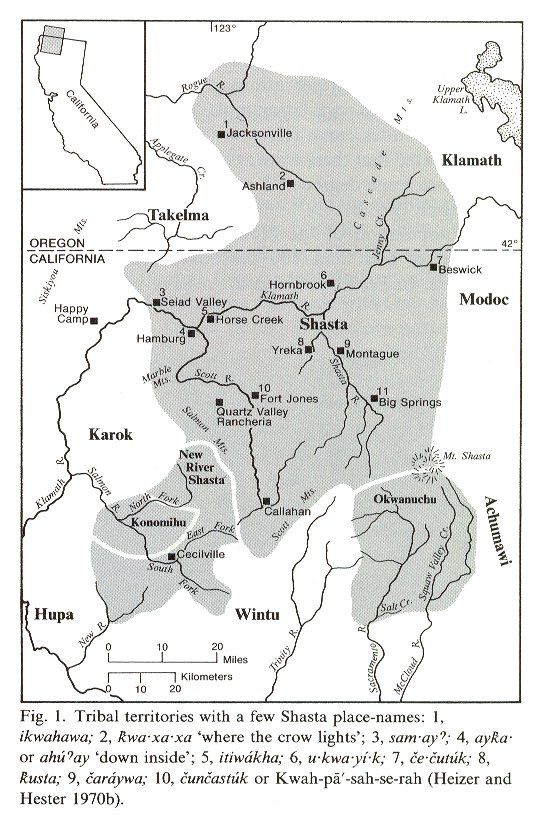

Next the trail would head towards the mining settlements on the Salmon River, crossing over into Shasta territory at the first forks of the river.

The Shasta people were hunters, fishers, and gatherers who lived semi-nomadic lifestyles. They hunted in the summer, building wickiups as temporary shelters. In the winter, they lived in villages of semi-subterranean oblong plank houses.

Primarily they ate acorns, seeds, and roots, but the fish, particularly salmon, was an essential factor in the food supply. They utilized broad, clumsy dugout canoes for fishing.

The estimated pre-contact Shasta population in California was approximately 6,000 people.

The first recorded encounter with Europeans was in 1826, when a Hudson’s Bay Company expedition came into the Klamath Mountains to trap beaver. Shasta favorably received them. The first population decline occurred from 1830-1833 when fur trappers spread a malaria epidemic. By 1851, the adverse effects of the disease had reduced the Shasta population to 3,000. With the opening of the trade route from Oregon to California by way of Sacramento Valley in the middle of the 19th century, the Shasta came more into contact with civilization.

Talking History of the Salmon River:

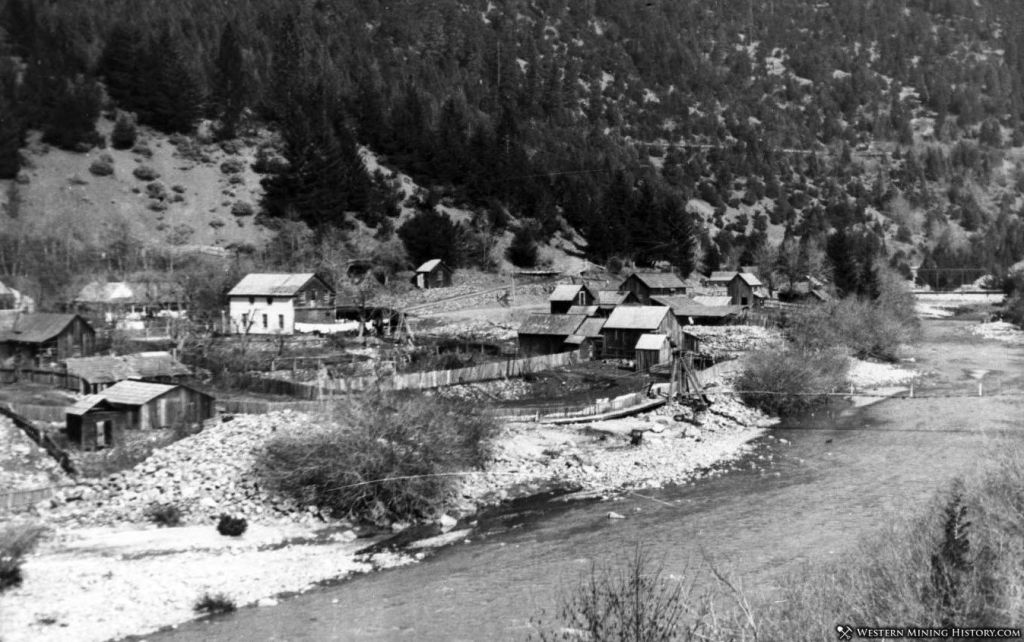

At first the trails into the Salmon River were long established game trails. Many of the miners arriving from ships on the coast came into the Salmon River along the trail running the ridge of the Salmon Mountains…

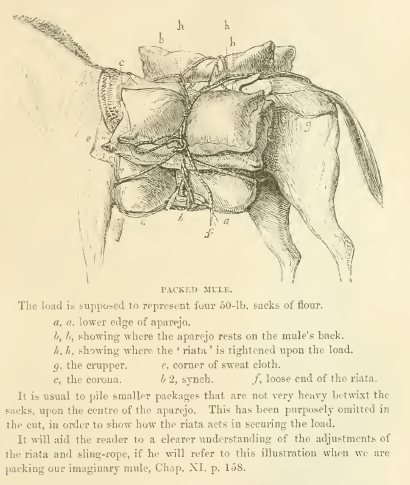

The first travelers in the 1850s dreaded the ‘Rocky Point’ on Salmon Mountain. It was a place where the trail was blasted or picked out of the solid rock, and was so narrow that a pack animal could not turn around. If two pack trains met at this point, it was a matter of life and death for the mules, and often one had to be unpacked and turned about, or even pushed over the precipice to allow the other to pass.

Pack trains early crawled the mountain passes taking food stuffs and supplies to Sawyer’s Bar, for there was no other way to get them there.

The trip from Etna, then known as Rough and Ready, to the Salmon River mines was a distance of some twenty-five miles of the most rugged travel imaginable.

The city of Etna began in 1853 with the construction of a sawmill.

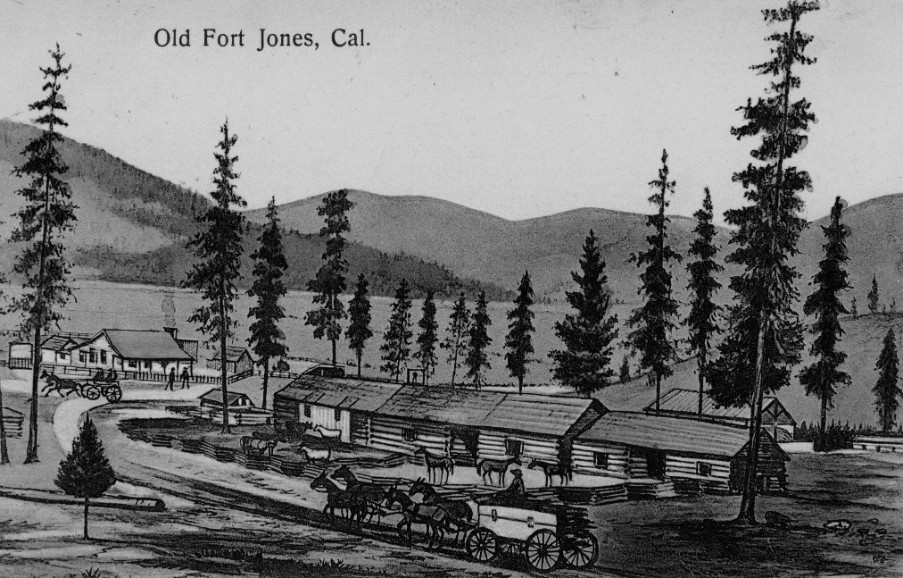

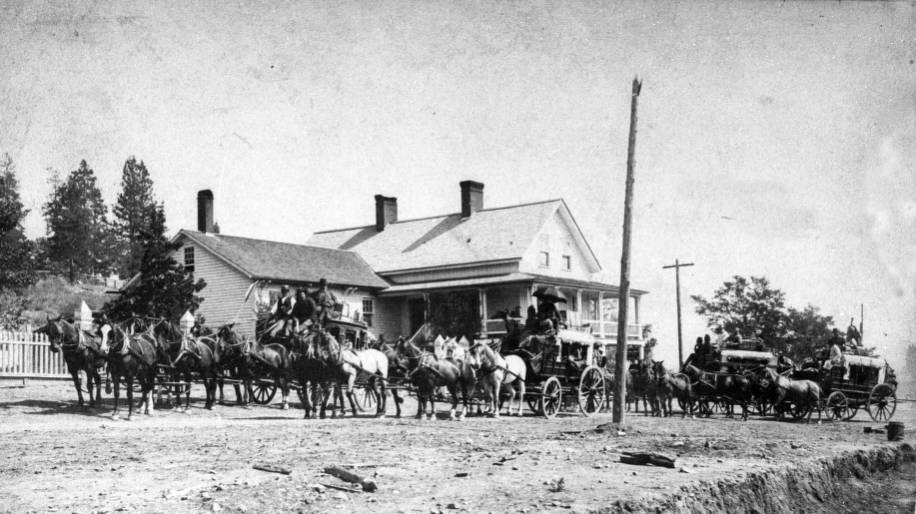

Fort Jones was established on October 18, 1852, by its first commandant, Captain (brevet Major) Edward H. Fitzgerald…

Such military posts were to be established in the vicinity of major stage routes, which would have meant locating the post in the vicinity of Yreka, sixteen miles to the Northeast. The areas around Yreka did not contain sufficient resources, including forage for their animals, so Capt. Fitzgerald located his troop some sixteen miles to the southwest, in what was then known as Beaver Valley. Fort Jones would continue to serve Siskiyou County’s military needs until the order was received to evacuate some six years later on June 23, 1858.

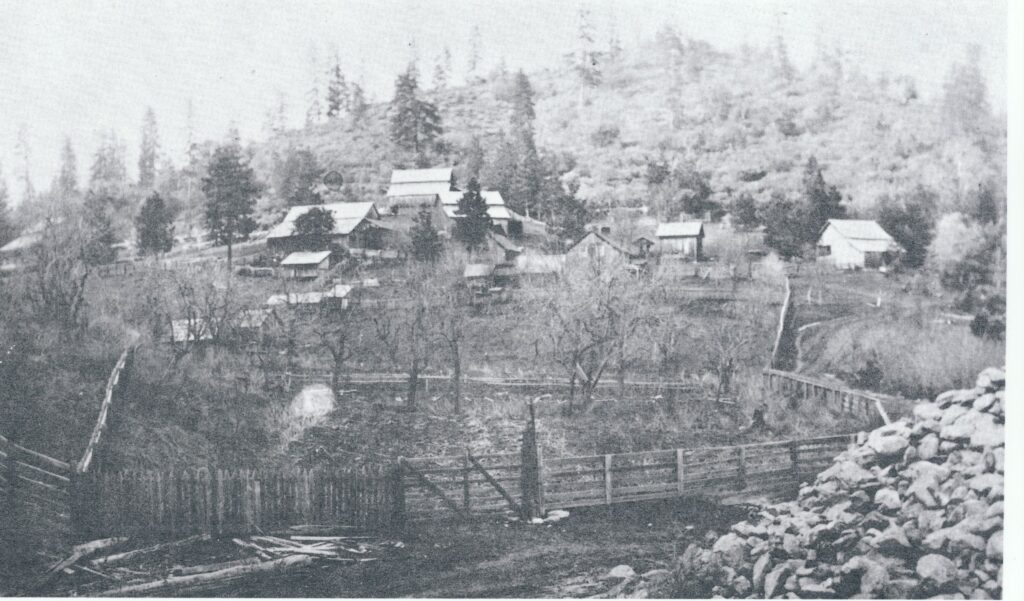

The Forest House Ranch “centered upon the Forest House itself, a two-story, wood-frame, building built circa 1852 on the Yreka-Fort Jones Road.”

“…the ranch and mountain inn… in its heyday boasted the largest apple and fruit orchard in California, produced its own wine, and was popular with travelers and neighbors alike.” – As It Was

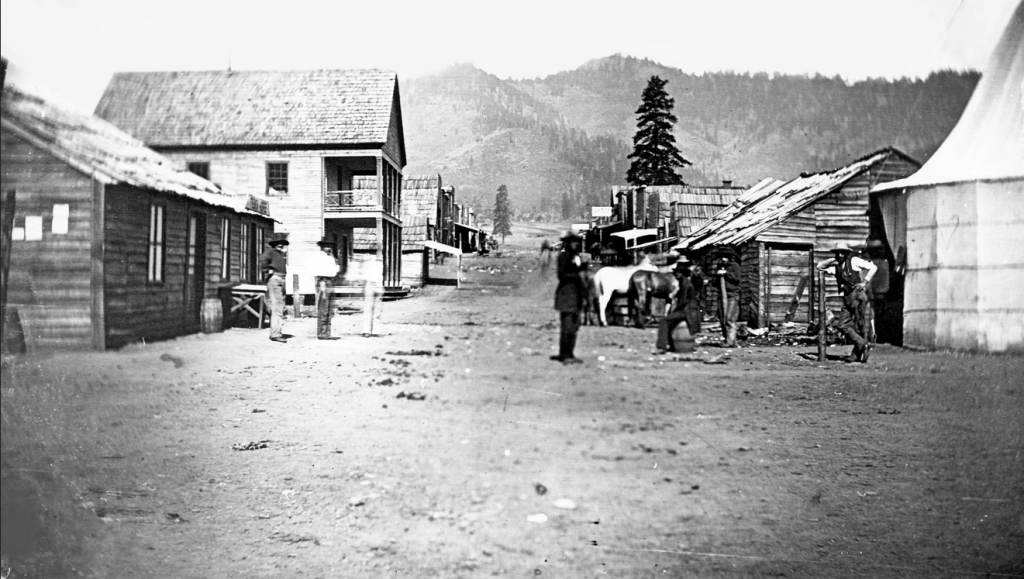

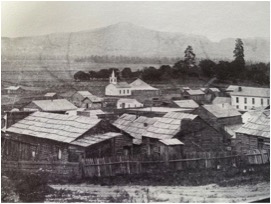

Founded in March 1851 with the discovery of gold in the nearby “‘flats,” Yreka quickly became the commercial and transportation hub for the surrounding communities and mining camps.

Yreka’s tents and shanties gave way to more substantial commercial and residential buildings seen on West Miner and Third Streets which remain as tangible evidence of the town 19th-century regional prominence. – Historical Marker, Yreka

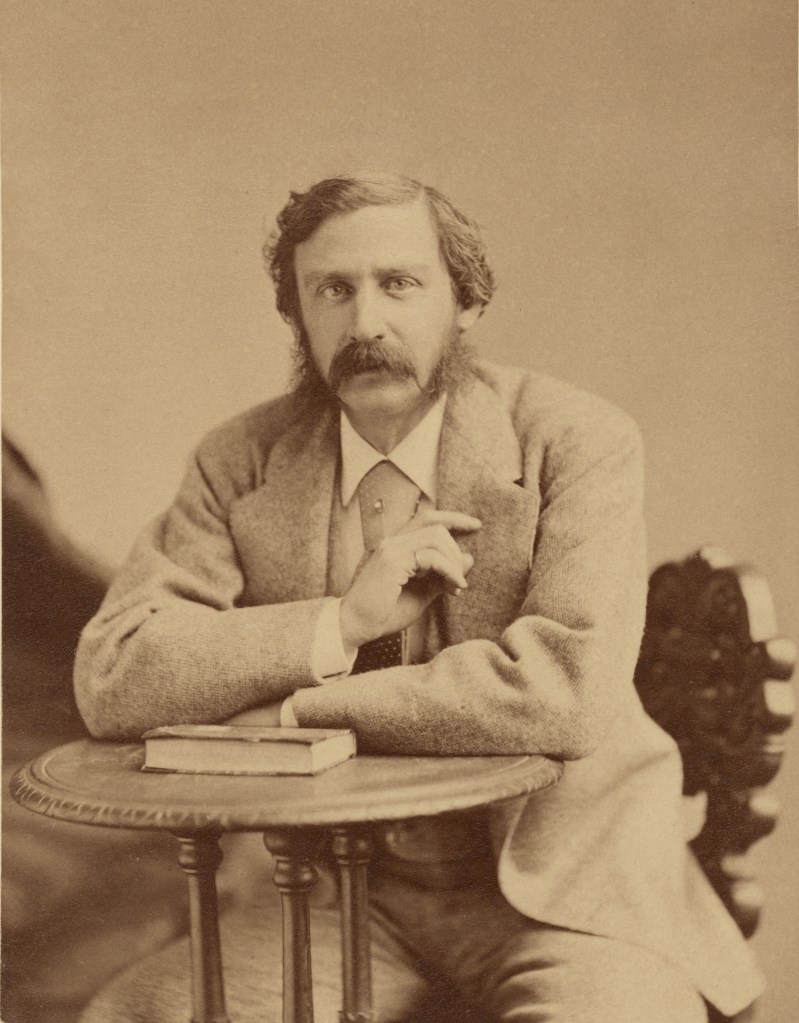

Mark Twain tells an apocryphal tale of the naming of Yreka relayed to him by his mentor/collaborator/rival Bret Harte:

Harte had arrived in California in the fifties, twenty-three or twenty-four years old, and had wandered up into the surface diggings of the camp at Yreka, a place which had acquired its mysterious name – when in its first days it much needed a name – through an accident. There was a bakeshop with a canvas sign which had not yet been put up but had been painted and stretched to dry in such a way that the word BAKERY, all but the B, showed through and was reversed. A stranger read it wrong end first, YREKA, and supposed that that was the name of the camp. The campers were satisfied with it and adopted it.

John E. Smith:

From there (I traveled) overland to Jacksonville, Jackson County, Oregon.

Nelson Bowman Sweitzer, 1854:

There were no wagon roads at this time from Shasta or Yreka to Jacksonville over the mountains, and no wagon roads from Jacksonville to the coast. All the transportation was on pack mules.

The Journals of James Mason Hutchings retrace that journey a couple years later, when the many of the same paths were still the primary routes, although some new roads had recently been cut for stagecoach travel.

February 3, 1855: Fine in morning, cloudy in evening.

From Yreka to Cottonwood, 18 miles.

This morning, being anxious to see Oregon, I left Yreka about 1 o’clock a.m. on my way to Jacksonville, Oregon, and passing some low hills from Yreka entered the Shasta Valley. Saw before me in full view to the very foothills that king of California mountains “Shasta Butte,” its white head and timber-covered base forming an inexpressibly magnificent scene of sublime grandeur.

There is also as soon as we enter a good view of Sheep Rock–though what there is either to give it the name or make it remarkable except as a small hill like any other I have yet to learn.

Saw however several little companies of sheep further down the valley, most of which had two lambs each that were skipping about–which reminded me of my own loved home. The grass is good in this valley–the snow having melted off except here and there where the sun could not reach it.

Forded the Shasta River about 2 miles from Yreka. This is a swift stream about 30 feet in width and about 3 feet deep in the middle–will average about 2 feet deep all across. I was afraid my horse would be taken off his legs and prepared myself for a scramble–one couldn’t expect to swim–but “fortune favored the brave”–and luckily, for a cold bath on a cold day makes one’s teeth “chatter” at the very thought of it.

There is a large amount of quartz in this valley and several “leads” at the base of the low hills around which you pass.

Took dinner at the Eagle Ranch–“Price’s”–a Welshman. My horse rolled and broke his stirrup!!!

There are some good farms near Price’s–men very busy plowing.

Leaving the Shasta Valley, we ascend a low divide between the Shasta and Klamath rivers. On this divide had a fine view of the Siskiyou Range of mountains–a prominent point of which is “Pilot Knob”–a bold and singular rock standing alone, high above the range.

Descending the sloping hills towards the Klamath found the road heavy and muddy with a sort of thick clay. Reached the Klamath River–16 miles from Yreka. Here at the upper ferry this river is about 300 ft. wide and about 15 ft. deep–as large a stream as the Sacramento at Shasta. This ferry is about 150 miles above the mouth of the river and about 60 miles below the Klamath Lake where this river takes its source or rise. There is a good house, but badly kept.

About 1½ miles from here crossed the Cottonwood Creek, a stream about 15 feet wide and 18 inches deep.

Sunday, February 4, 1855: Light floating clouds and warm.

Cottonwood to South Mountain House, 8 miles.

The people here being busy playing quoits (or horseshoes) and noisy, I thought I would seek retirement out of town, so I accompanied a miner around the adjoining hills.

I have always thought that some sea current has set from northwest to southeast over the whole of Cal.–in what is known as “the mining region”–as large quartz and other boulders of immense size–and water-worn–interspersed with smaller gravel of immense depth–and also wood has been found on the highest mining hills. Today I saw petrified sea shells in large quantities forming a conglomerate rock–also some oyster shells in the same state! Yet this cannot be less than 4 or 5,000 feet above the present level of the sea.

The Hornbrook Formation is what happens when the floor of an ancient ocean gets thrust upwards by 2 tectonic plates colliding. It stretches from Yreka to Jacksonville.

There is large quantities of quartz gravel all around here.

“Cottonwood” is the name of the neat little mining town in the valley of the creek of the same name about ½ a mile distance from the creek, being 18 or 20 miles north of Yreka and about a mile from the Klamath River.

There is a large number of men around here, nearly all “broke.” After dinner is [over] I could not endure the noise. I rode on, and the day is warm and pleasant, resembling a spring day.

Between the head of Cottonwood Ck. and “Cole’s” or “Mountain House” there is plenty of mud in the trail–or rather sticky clay, especially where the recently melted snow has saturated the ground. The road in the summer I should think very good, being without any hard hills to cross.

Didn’t meet a soul–until about 6 miles on my way, when I overtook a man with a train of animals he was ranching. I learned from him that mules are generally more cunning and intelligent than horses. “A few days ago,” said he, “I rec’d. that poor horse you see yonder”–pointing–“and the other animals, especially the mules, look down upon him–kicking and biting and striving to drive him out of the train.”

I thought a mule is not the only animal that looks down upon poverty. One mule does not follow the scent to find out where the band is grazing, but ascends the hill yonder in the center of the valley, and then when he see them starts off full gallop to join them.

All the animals, he thought, displayed considerable mind–a favorite theme of mine–as I believe that we do not give God credit for making his works as perfect as they really are.

The Cottonwood men pitch horseshoes as their only “pastime” on Sundays.

February 5, 1855: Cloudy & warm.

From South Mountain House to “Eden” School Dist., Rogue River Valley, 22 miles.

Had pretty good quarters last night at Cole’s (M.H.) [Mountain House].

Hughes’ [Hugh Barron’s] Bear Valley is two miles north of [Cole’s] Mountain House.

From Cole’s to Rogue River Valley–a distance of about 14 miles–the road is very heavy and clayey mud. The horse feet when drawn out go off like corks from large bottles, such is the suction of the mud; at other times the water from an old hoof hole would squirt 6 or 8 feet above one’s head when on horseback. Plug! plug! plug! would be the music.

From Yreka to the Siskiyou Mountains there is but little timber (except in the distance), but having reached the summit in descending towards the Rogue River Valley the forest timber is very heavy and dense. How a stage gets over that road I can’t say upon oath. I know that it was as much as my horse wanted to do to get along without my riding.

When you get a distant view of the Rogue River Valley you are struck with the beautiful green slopes and clumps of oaks and pines on a rounding knoll here or there with the smoke curling up from one of those woody dwelling places. The mountains too (although on the northeastern side of the valley are without heavy timber) are beautiful from their singularity of shape and greenness of surface.

The climate of this valley must be more moist than in California, as I see the grass roots do not die here from excessive drought, while every hill has a number of animals grazing on the top, for the grass is good although the snow has not been off the ground over a month.

Met a lady sitting astride her mule the same as the two men with her. She didn’t exhibit much of the beauty or ugliness of her understandings. I must say I like to see a neat ankle on a woman! She had one, and I of course had to admire–consequently, looked!

The Siskiyou Mountain is easy and gradual of ascent and not very high. Met several pack trains laden with goods for Yreka–they having come by way of Crescent City and Jacksonville.

Now, as the Rogue River Valley opens to the view, how beautifully diversified is the scene–now fine clear openings of rich, black soil just turned up by the plow–now the young wheat fresh and green peeping from the soil; here and there a small stream running down from the timber-clothed mountainside that would turn a mill or color the flower or give vitality to crops–here a small swell of land covered with oaks–there one of pines–yonder another with that beautiful evergreen the “manzanita” and other bushes.

February 6, 1855: Cloudy–rain & cold in the morning–not much better evening.

From “Eden” (or “Rockfellow’s Tavern”) R.R. Valley to Sterlingville, 12 miles.

Was only charged $3.00 for myself and horse for last night!!! Good.

Kept threading my way round fences and houses for about 4 miles further down the valley, when I left it following a trail towards Sterlingville–a much higher and more difficult mountain to climb than coming over the Siskiyou Range.

Grass on every hill–good grass–and on the distant hills could see cattle grazing.

Reached Sterling about 2 o’clock.

This is a small town that has newly sprung up, the diggings not having been found more than 7 or 8 months, but there are now in the vicinity about 550 miners–about 20 families–no marriageable women–about 35 children.

It is a busy little spot–the hillsides and gulches are alive with men at work either “stripping” or “drifting” or “sluicing” or “tomming” or draining their claims by a “tail race.” Yet the water is thick with use–being very scarce–as a large number of men are using it. Here you see a prospector with his pick on his shoulder and a pan under his arm, and his partner coming along with the shovel upon his shoulder. That man yonder with the blankets at his back has just got in–he is now asking if you know anyone who wants to hire him. You tell him where you think he may live for a few days, and when that fails he will have money enough to buy himself some tools and set himself to work.

There as everywhere the cry is water–water–“will it never rain”–yes–“they feel dull enough” for they can’t make their board for want of water. They ask you “if the people at Yreka are doing anything yet?” “No,” is your answer. They want water–the canal not being finished yet, things are duller there than here. “Had I seen anything of a man named Brooks who was coming to see if he couldn’t bring in Applegate Creek to set the men doing something with the water?” No, I hadn’t. “Well, he was a-coming.” That’s the talk, said I. This town is situated on Sterling Creek about 5 miles from its junction with Applegate Ck. The creek is about 8 miles long.

February 7, 1855: Cloudy & a few drops of rain

Down Sterling Creek to its mouth called Bunkumville [Buncom], 5 mi.

Left Sterlingville to go down the creek–for about a mile and quarter down–on the hillsides men are very busy the same as in town; many are doing remarkably well with the little water they now have.

There is but little mining in the creek.

Then further down you go for 2½ miles before you see anything being done–not a man to be seen–then a prospector or two, then a couple of men at work, then a company, then more prospectors. Then cabins are seen and in the distance a flag–perhaps a piece of old canvas tied to a pole (although sometimes the stars and stripes are floating proudly as if to say “walk in–there’s liberty here–to get drunk if you have money or credit”). At all events it indicates a trading post.

Opposite to that the rocks and the water and the pick or the shovel or the fork are rattling in or about the sluice boxes–people are all hard at work. What a contrast to some places.

As I was looking and thinking how much these diggings resembled White Rock in El Dorado Co., a voice hailed me, “Why, how do you do Mr. H!” and a hearty grip of the hand from Jim Lamar, a man who worked for us at White Rock. It was rather a singular coincidence.

The gold here is generally rough–not having been washed smooth by rolling as in some districts.

I prophesied good hill diggings here same as at White Rock.

February 8, 1855: Cloudy and dark. Rained ¾ an hour last night.

Sterlingville.

Last night it rained for about ¾ of an hour, and as I felt it pattering on my head I didn’t approve of such an unfeeling course. I however moved further down in bed and covering my head with the blankets told it to rain on–but it didn’t for long. Still it is an unpleasant situation, sleeping in the best hotel! of the place to find that when the rain can get at your head you feel its cold “fingers” down your back. Such is hotel accommodations here. There is moreover two women to cook–yet nothing fit to eat–went without dinner rather than go to eat it.

February 9, 1855: Rained lightly all the morning, but held up at noon.

From Sterlingville to Jacksonville, 8 miles.

This morning it was rather unpleasant traveling in the rain; the road, however, is of a very gradual grade–but a large portion being through a timbered country, the roots across the road and on the ruts make it rather hard I should judge for wagons–there are so many soft places near the roots and stumps a wagon has to cross.

Sterling Mine Ditch Trail offers similar views in the region that travelers like Hutchings and especially Smith would have observed, although the highway has directly replaced the paths they took. Sterling Mine Ditch was one of the solutions to the miners’ water problems, carrying water to the Sterling Mine from the 1880s to the 1930s.

One fellow had taken himself up a ranch and was fencing up [i.e., across] the road–without in any way indicating any other way–and I accordingly got from my horse and threw down the fence at the trail. Men must be “darned” fools to suppose that strangers will spend their time hunting for a new trail when the plain one–with a fence across it–is just before him. I’ll bet that fellow was from either “Pike” or “Oregon.” It is too general sometimes turning teams a mile or two round and up a bad hill.

About noon I reached Jacksonville. This is the county seat of Jackson Co., Oregon and was formerly called “Table Rock City.”

Diggings were first discovered near here in Feby. 1852 by Messrs. Clugage & Pool, who being on a prospecting tour found their labors rewarded by the discovery of good diggings. There were but three log houses in the Rogue River Valley then–for farming purposes.

A.J. Walling, History of Southern Oregon:

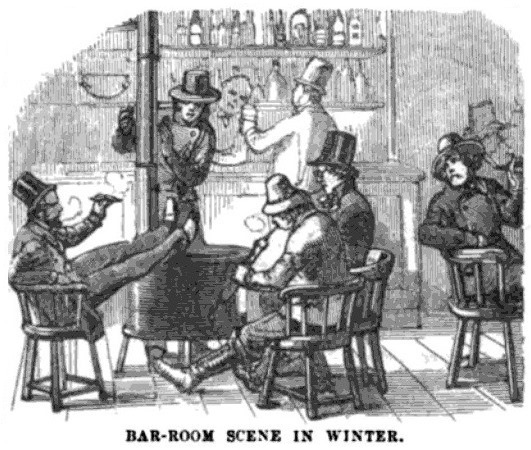

… a trading post was opened in a tent by Appler & Kenny, packers from Yreka. It was by no means a bazaar, the stock comprising only a few tools and a little “tom iron,” the roughest clothing and boots, and some “black strap” tobacco, and a liberal supply of whisky-not the royal nectar, perhaps, but, nevertheless, the solace of the miner in heat or cold, in prosperity and in adversity. Other traders followed, bringing supplies of every kind, pitching their tents on the most available ground, and finding plenty of customers flush with treasure.

In March the first log cabin was erected by W. W. Fowler, near the head of Main, the only street in the embryo city. Lumber was “whip-sawed” in the gulches, at the rate of $250 per thousand, or purchased in small quantities from a saw mill up the valley; clap-board houses, with real sawed doors and window-frames, began to rise among the tents; the little, busy town emerged from the chrysalis state, and before the end of summer assumed an air of solidity, and fairly entered on the second stage of its existence.

During this time a marked change had taken place in the social structure of Jacksonville. Gamblers, courtesans, sharpers of every kind, the class that struck prosperous mining camps like a blight, flocked to the new El Dorado. Saloons multiplied beyond necessity; monte and faro games were in full blast, and the strains of music allured the “honest miner,” and led his feet into many a dangerous place, where he and his treasure were soon parted.

The progress of Jacksonville in 1853, was marked by the accession of many respectable families. Hitherto, Mrs. Napoleon Evans, Mrs. Jane McCully and Mrs. Lawless, had made up the sum total of ladies’ society. The emigration of this spring poured in a large number of settlers, many of whom occupied the rich lands of the adjacent valley while others located in the town.

The improvement in society was more apparent than in the town itself. Many buildings were erected but they were neither ornate nor durable, being hastily constructed, and only to serve the necessities of the hour. Owing to the fact that all supplies were brought in on pack animals, not a single pane of glass was used in Jacksonville that year, but cotton drilling was a reasonably convenient substitute.

Drill fabric is (typically) used for work clothes, trousers, skirts, uniforms, outdoor furniture, awnings, and protective coverings for machinery.

The diagonal bias in the weave gives the fabric a similar strength to denim.

Anne Ellis, The Life of an Ordinary Woman:

“The windows were of cotton drilling, and the light that came through was a soft, gray light. It was always like twilight in the house, even on the brightest days, and when the wind blew, the windows would belly in and out with a soft, muffled sound.”

Next time:

At Jacksonville, Johnnie Smith freights from Crescent City, on the coast near the California line, to Jacksonville.

Leave a comment