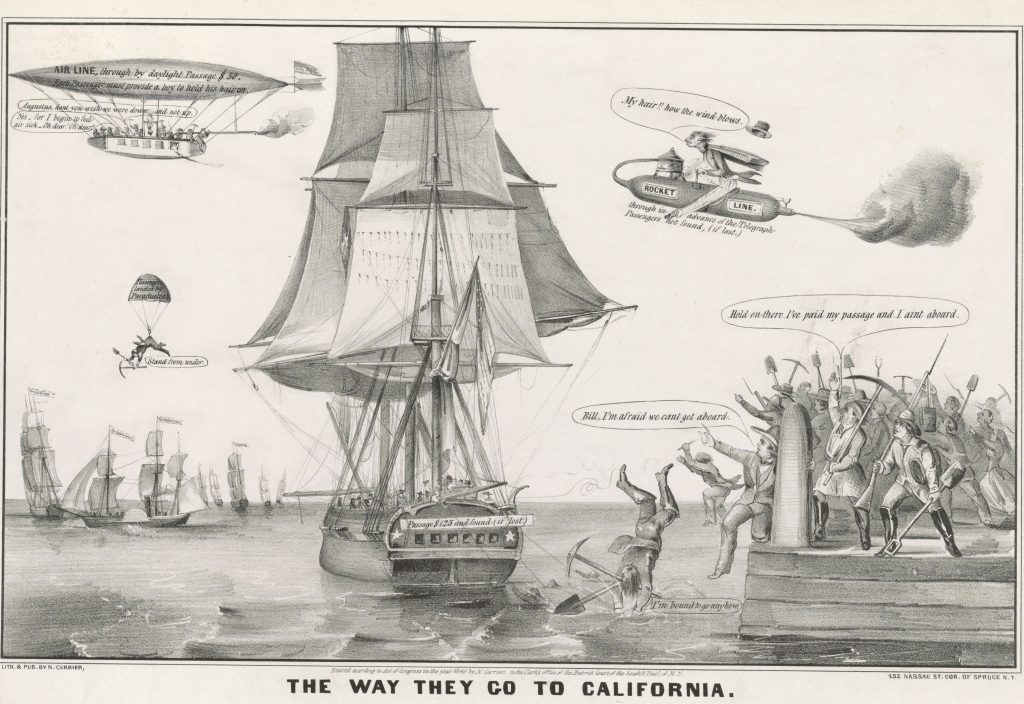

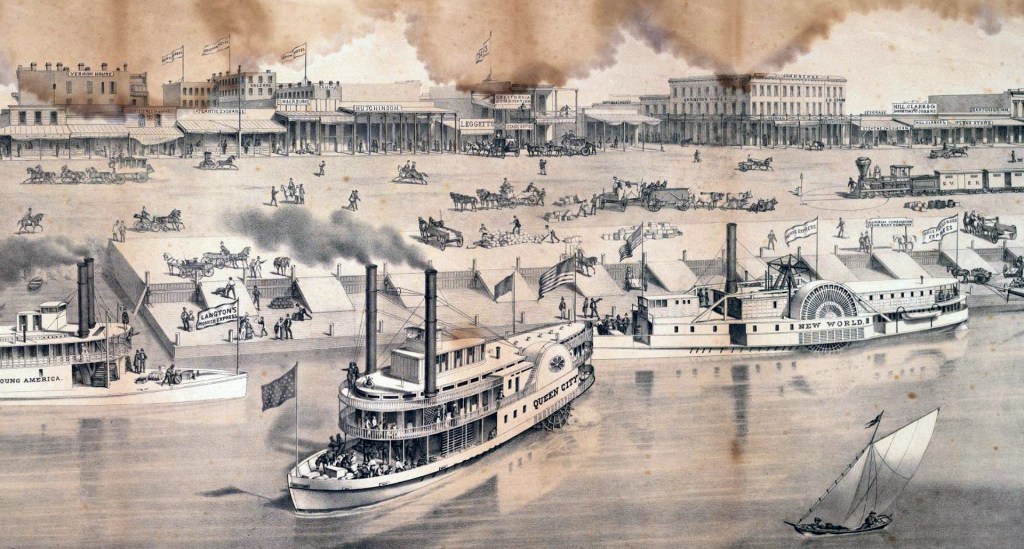

Previously: In 1849, when Johnnie Smith was a lad of fourteen years, he sailed from New York for California as a cabin boy around the Horn. In California he shipped on a steamboat carrying freight and passengers from San Francisco to Sacramento.

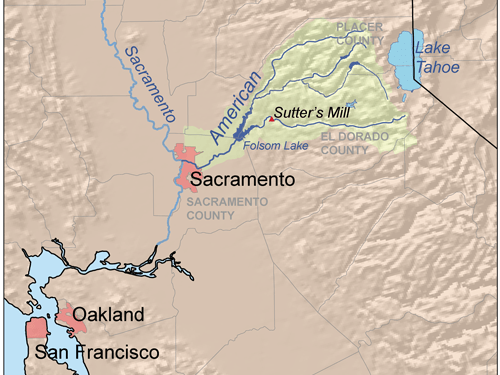

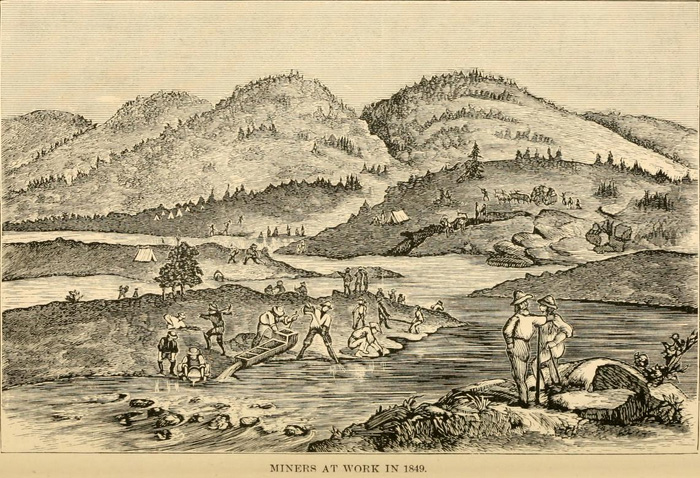

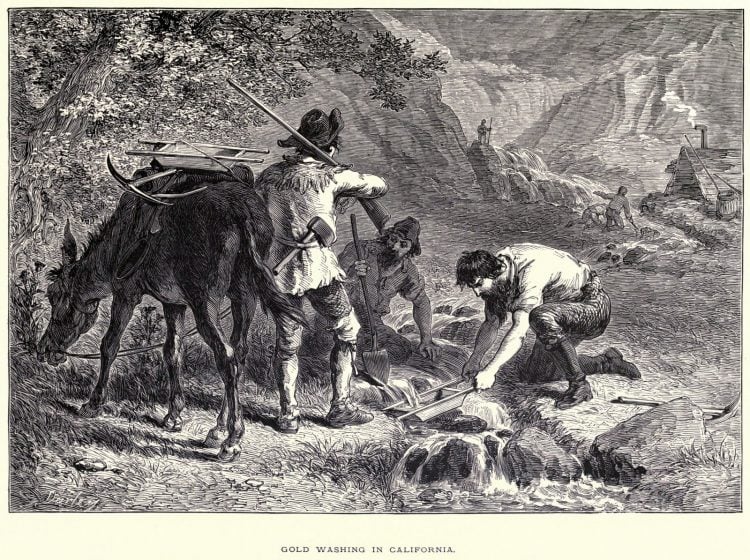

Later I went from Sacramento to the North Fork of the American River, where I placer mined.

I wonder how long our boy worked on that river boat before catching Gold Rush fever, but I’m sure it was unavoidable. Perhaps that was what brought him to the west coast in the first place. It’s just interesting to see how a lad who grew up dreaming of the sea got that out of his system after one arduous voyage. Suddenly the western adventure was far more compelling.

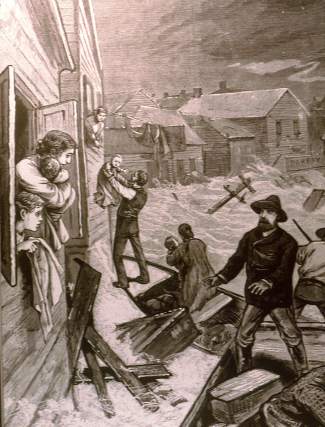

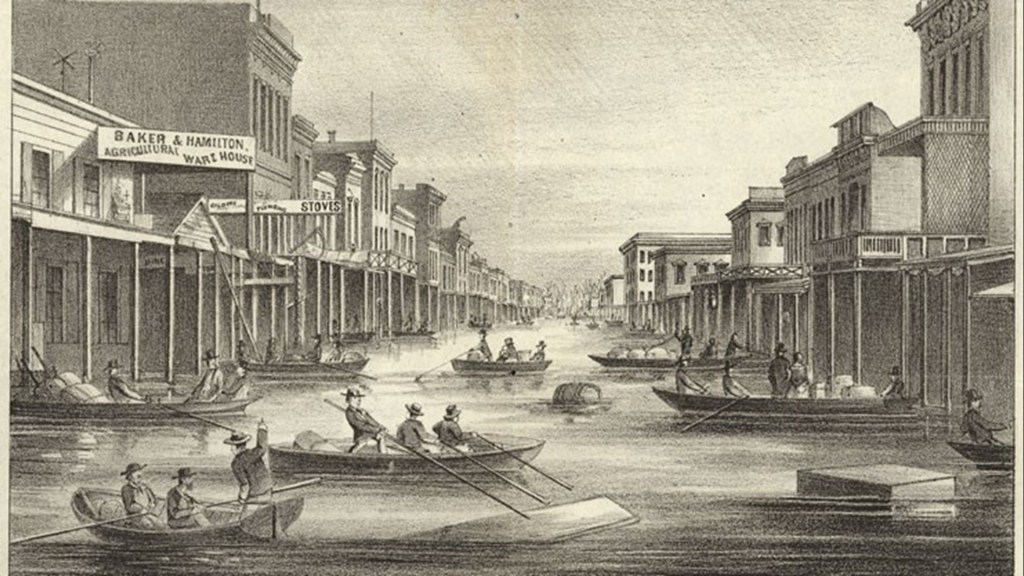

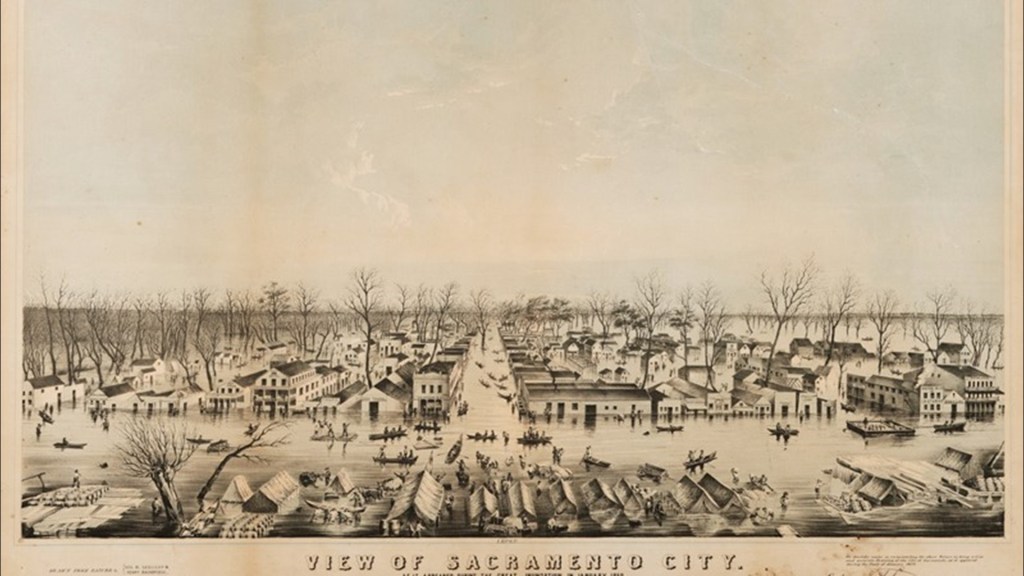

Considering his stint aboard the McKim didn’t begin until late October, I’m guessing he didn’t leave the Sacramento area until the next spring. The winter of ‘49 was notoriously difficult for miners, with record rainfalls that began in October bringing flooding in the Sacramento Valley by January.

A Sacramento news station recalled the event on its 170th anniversary in 2020:

The river barreled over, sinking the streets of Sacramento in 6-feet of water. It was streaming fast, flooding the hotels and houses of Gold Rush migrants hoping to find fortune in the bountiful land of California.

“This will be a day never to be forgotten by the residents of Sacramento City as a day that awoke their fears for the safety of their city against the dangers of a flood long since prophesied,” a horrified witness described to The Daily Alta California as he watched his city ripped apart in 1850.

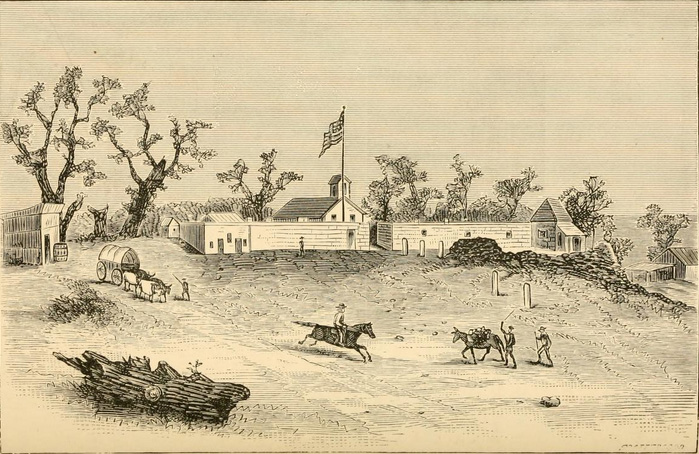

Rescue operations were conducted by boat, taking those rescued to Sutter’s Fort, which stood on high enough ground not to be flooded.

Way back when John Sutter had canvassed the land, Native Americans had warned him of the “inland sea” of the valley. They advised him to locate Sutter’s Fort above the plain.

However, new settlers in Northern California lived close to the river, where boats would sail into port and visitors stopped for food and lodging. As such, Sutter’s Fort had the high ground; it was an oasis for stranded individuals and animals during the flood of 1850.

According to Jessica Knox-Jensen, Assistant Chief of the State Library Services Bureau, the decision to live at the water’s edge was not as foolhardy as it may appear.

“It’s not surprising that folks chose to settle on the waterfront because it was probably the most convenient location for commerce,” Knox-Jensen said. “Sacramento was in an advantageous location, given that we’re at the confluence of two rivers, and the river was a driving force in commerce for the city at that time.”

However, the waterfront was doomed when the floods came. The rushing waters uprooted homes and drowned livestock. According to the Daily Alta witness, “Far as the eye could reach, the scene had now become one of wild and fearful import—floating lumber, bales and cases of goods, boxes and barrels, tents and small houses were floating in every direction.”

Daily Alta California, 16 January 1850:

Long before noon hundreds of boats were crossing every street, far and near, and bearing to the several vessels that lay at the river’s bank, women and children, the sick and the feeble; and as they arrived, the owners of the vessels were ready to offer them prompt aid and every comfort in their power; and when they were safely landed upon the decks, the shout of joy went up to heaven in loud cheers from those who landed them, for their safety, and these shouts were echoed back by the hundreds of voices that were in the surrounding boats, and within hearing of the response. During the entire day and until night, this work of humanity and mercy went on.

As an evidence of the power of the current, the new and valuable brick building, corner of J and 3d street, built at great cost by the Messrs. Merritt, having walls nearly or quite 18 inches in thickness, was undermined, and fell with a heavy crash, carrying with it the next store, Messrs. Massett & Brewsters, with which it fell into the flood a mass of ruin. The large iron store on K street, was lifted from its position, carried into the street, and then overthrown, and various others shared the same fate.

The City Hotel, where so many of our friends have enjoyed the excellent fare that was always provided by the proprietors, was so completely submerged as to compel the boarders to enter by boats, at the second story, the first being completely under water.

Meanwhile an early, heavy snowfall in the Sierras trapped miners in camps and made mining impossible for most of the winter. Starvation loomed for those who found themselves without adequate supplies, and what little goods could be obtained came at exorbitantly high prices. It’s hard to imagine John Smith heading out to begin his mining adventures in the worst of that.

I suspect as the initial two-boat duopoly on the river quickly expanded and became over-saturated with competition, the wages of those low on the totem went down with the price of tickets. What probably began as a pretty cushy gig for young Johnnie became less and less appealing, especially when riches were to be found out there in the wild world. But, at least he was on a boat when the floods came!

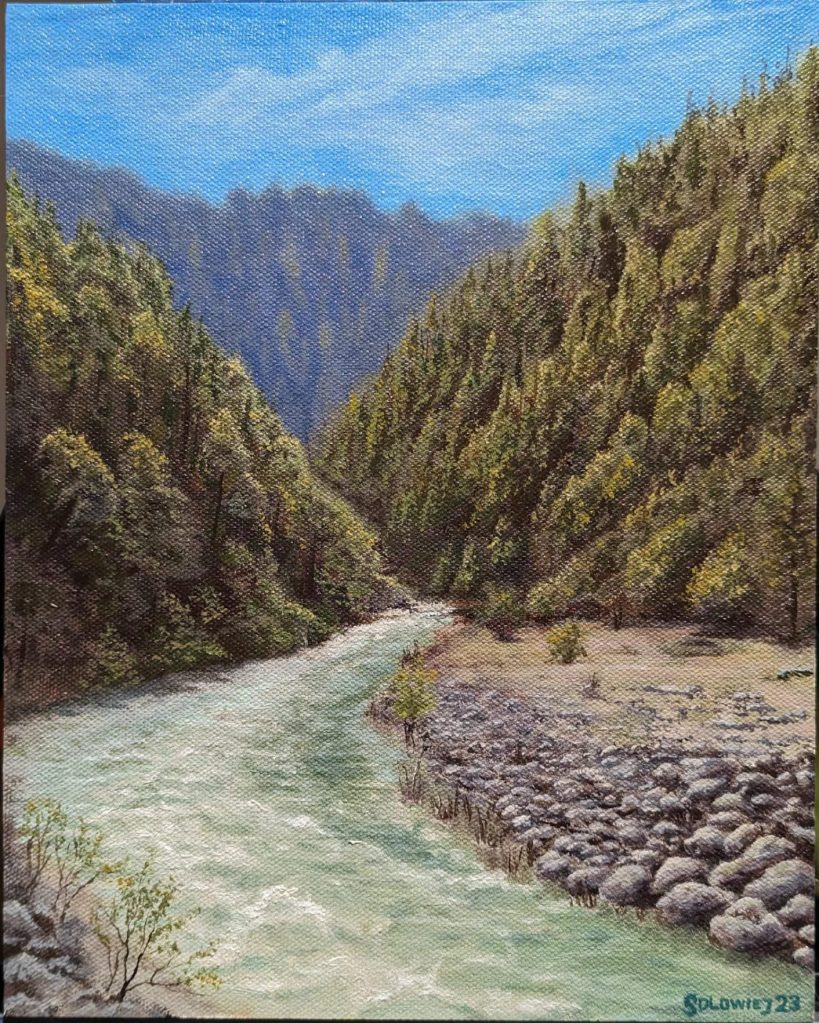

Once the weather got reasonable, heading into the foothills from Sacramento was the next logical step for Smith to take, with the North Fork of the American River known to be rich with gold-bearing gravels in the early years of the Gold Rush.

A “placer” deposit is where natural forces have caused precious metals to separate and then accumulate, in this case loose gold particles collecting in riverbeds and ravines. This is where you employ the classic gold pans to separate the gold from dirt and water to do simple placer mining.

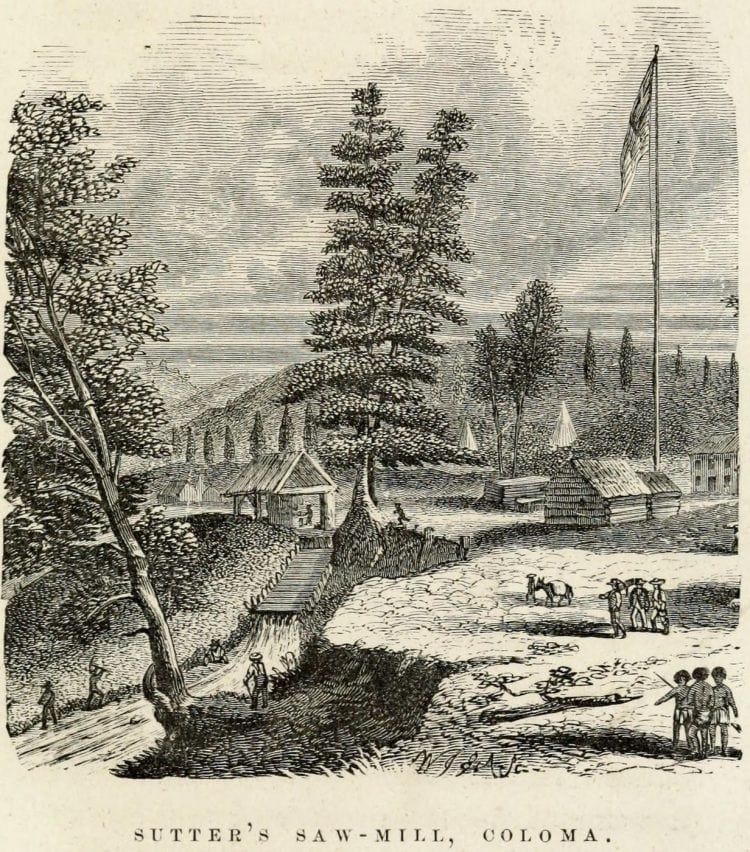

From there I went to Coloma, on the South Fork, where Sutter had his saw mill, and in the mill race of which the first gold had been discovered.

Sutter’s Mill was where the Gold Rush began. The “mill race” is a confusing term for us post-waterwheel folks; the “race” is not a competition but rather it’s the channel dug which causes the water to race to and from the waterwheel of the mill.

It was the digging of this channel during the construction of Sutter’s Mill which revealed the first tremendous deposit of gold in California.

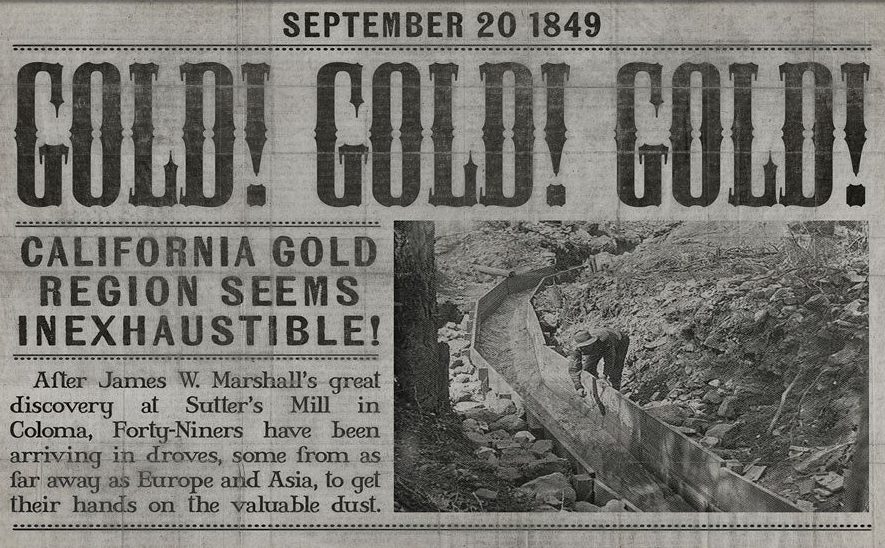

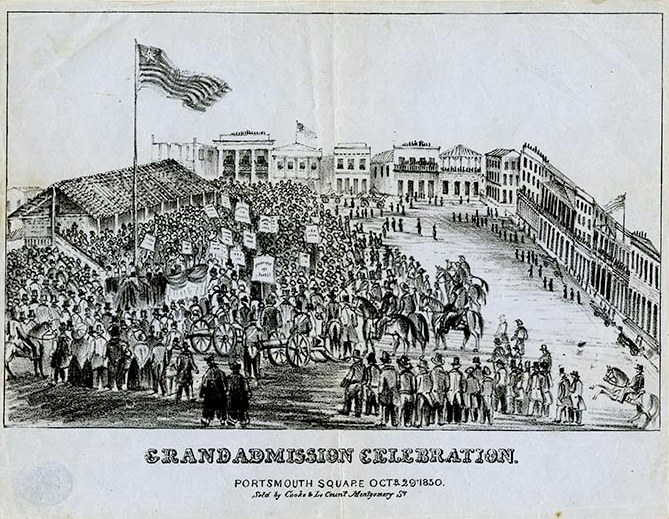

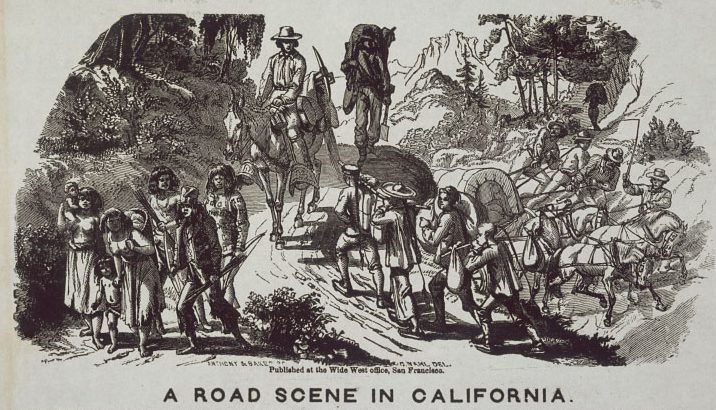

Prior to the Gold Rush, there were roughly 158,000 people in California. 150,000 of them were Native Americans, and 6,500 were of Mexican descent. Only about 1,500 were non-natives of European descent, a mix of US citizens and foreigners who emigrated directly to the new territories. By the end of 1849 this settler population would explode to over 100,000, all in search of gleaming riches. The sudden population increase of “49ers” was so dramatic that it required the fast-tracking of California statehood for the sake of law-and-order. Before the end of the next year it was the 31st state.

By the time Smith arrived a year after the first rush, the early easy pickings were gone. Coloma remained a central hub of activity, with many people still working on the river and the surrounding hillsides.

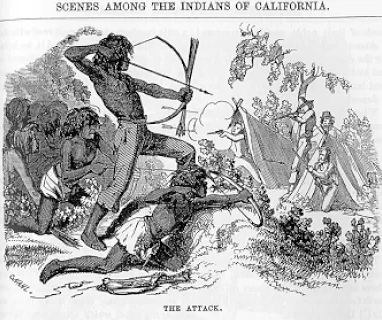

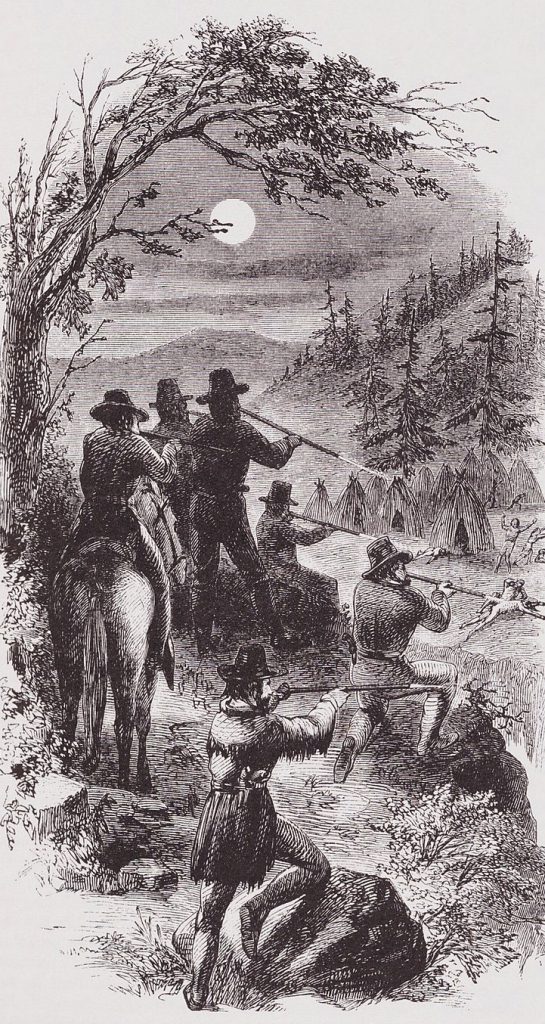

The massive influx of settlement brought steady conflict between miners and the native population. Miners were often directly hostile towards the natives, and rarely punished when they were the perpetrators of violence. Natives, meanwhile, had no way to defend or advocate for themselves in courts that would only accept English-language testimony.

To deal with the unrelenting flow of settlement to the west coast, president Millard Fillmore’s administration focused on securing treaties with the western tribes to give up their ancestral lands in exchange for annuities and the establishment of reservations.

By 1849 settlers were quickly moving into Northern California because of the discovery of gold at Gold Bluffs and Orleans.

Yurok and settlers traded goods and Yurok assisted with transporting items via dugout canoe. However, this relationship quickly changed as more settlers moved into the area and demonstrated hostility toward Indian people. With the surge of settlers moving in the government was pressured to change laws to better protect the Yurok from loss of land and assault.

The rough terrain of the local area did not deter settlers in their pursuit of gold. They moved through the area and encountered camps of Indian people. Hostility from both sides caused much bloodshed and loss of life. The gold mining expeditions resulted in the destruction of villages, loss of life and a culture severely fragmented.

While miners established camps along the Klamath and Trinity Rivers, the federal government worked toward finding a solution to the conflicts, which dramatically increased as each new settlement was established.

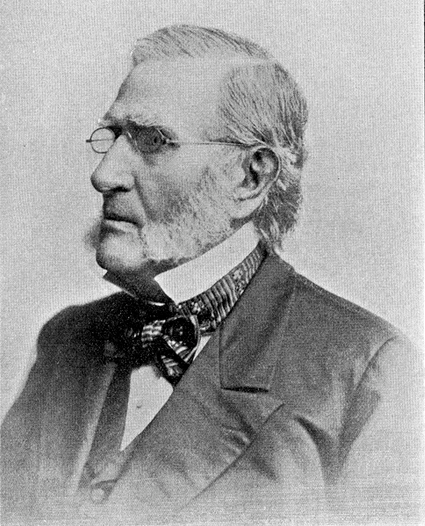

The government sent Indian agent Redick McKee to initiate treaty negotiations. Initially, local tribes were resistant to come together, some outright opposed meeting with the agent.

The treaties negotiated by McKee were sent to Congress, which was inundated with complaints from settlers claiming the Indians were receiving an excess of valuable land and resources.

The Congress rejected the treaties and failed to notify the tribes of this decision.

John E Smith:

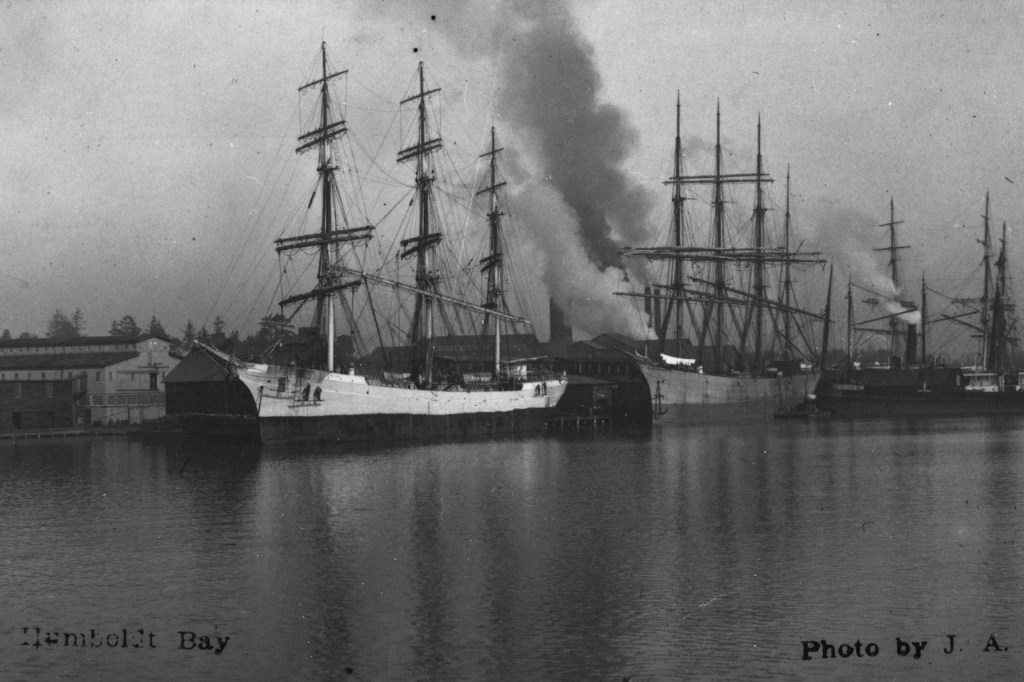

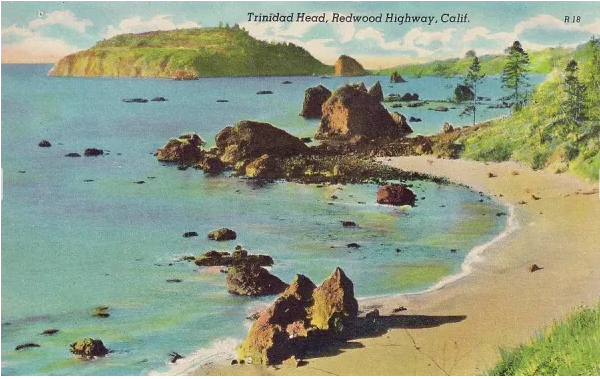

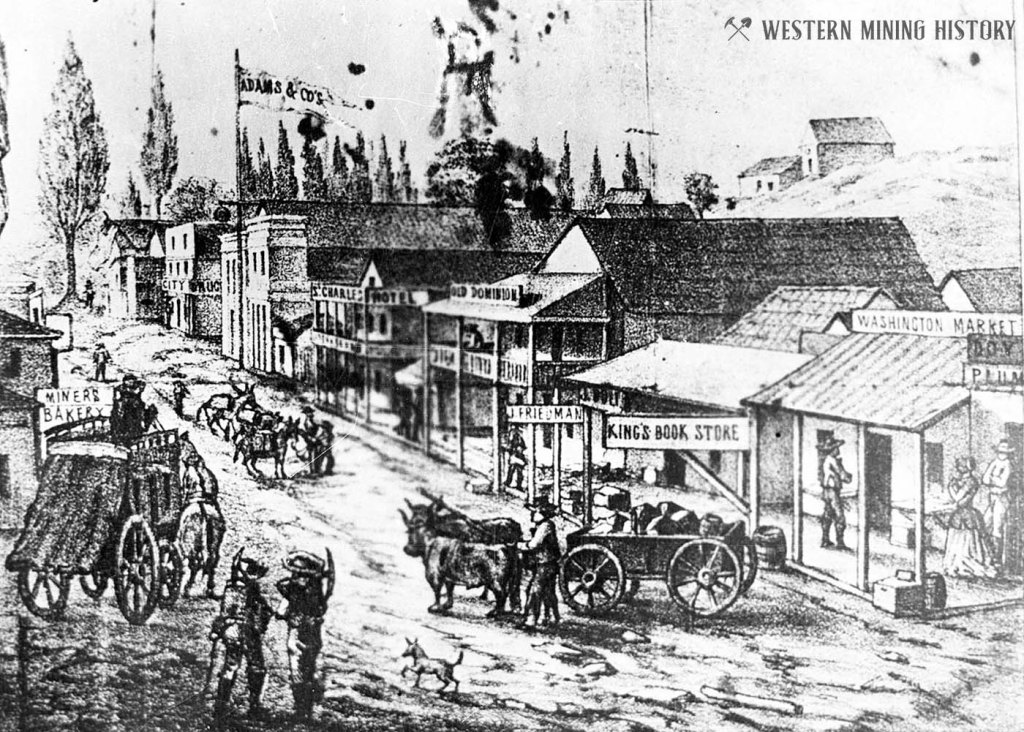

In 1852, I went by boat from Humboldt Bay, California, to a mining town called Trinidad.

Along the coast, settlements like Trinidad and those near Humboldt Bay were established to support the gold fields, leading to immediate conflict with the local Wiyot, Yurok, and Hupa tribes. The settlers’ demand for land and control over fishing resources quickly led to violent attacks and displacement.

Trinidad, established in 1850, quickly became a key port for supplying miners in the area. Since there were no reliable roads, a fleet of ships delivered goods, mail, and travelers to Trinidad Bay, where the cargo was then sent inland to mining camps along the river systems. While the area around Trinidad had some coastal placer mining at beaches like Gold Bluff, most of the activity it supported was further inland.

Then from there to Salmon River; from there to Scott’s River.

Elijah Steele recalled:

Up to February 1851 after my arrival in California I was a resident near Shasta in Shasta County in that state. Whilst there in the fall of 1850 I made the acquaintance of Genl. Joseph Lane, now delegate in Congress from Oregon Territory. Genl. Lane, being quite a favorite with the frontier men, was early informed of the prospects of Scotts River and vicinity and as early in the season of 1851 (and I think February) as the weather would permit set out for the new diggings and invited me to accompany him, which I did.

We arrived on Scotts River in the last of February of that year. Upon our arrival on the upper waters of Scotts River the Indians, who had heard of Genl. Lane through the Oregon Indians, learning that the Genl. was leader of the company, came into camp and expressed a wish that all hostilities between them and the whites should cease and that Genl. Lane should be “tyee” or chief over both parties. Up to this time during our journey, which had been protracted to eighteen days, we had been under necessity of standing guard both over animals and camp both day and night. This proposition of the Indians was a great relief to us.

Among the Indians who came in at that time were the chief of Scotts River Indians (calling themselves Otte-ti-e-was), whom we have christened John, and his three brothers, Tolo, now called “Old Man,” chief of the band inhabiting that part of the country upon which Yreka is now located, and the chief of the Cañon Indians as they are called inhabiting the cañon and mountains on the lower part of Scotts River including the bar.

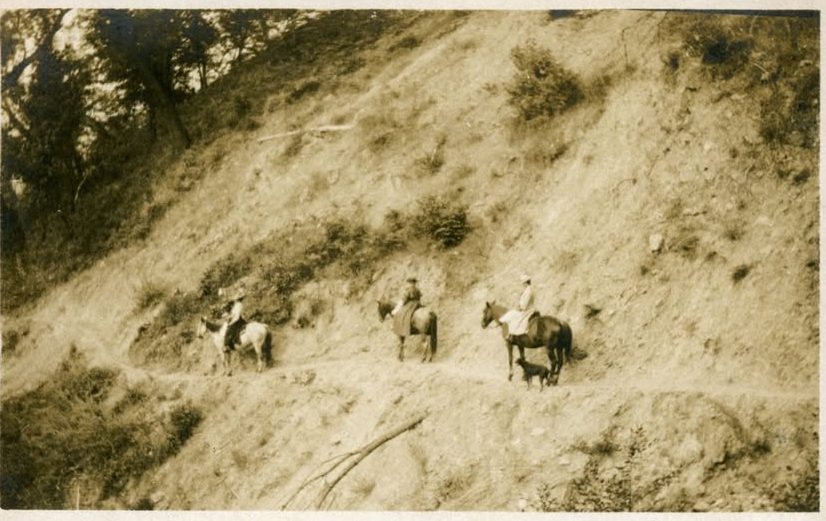

Miners used mule pack trains to access these remote locations, often facing difficult terrain as well as conflicts with Native American tribes. This could be where Smith first learned the basics of driving a pack train, skills that would serve him well later.

John E. Smith:

From there to Yreka, California.

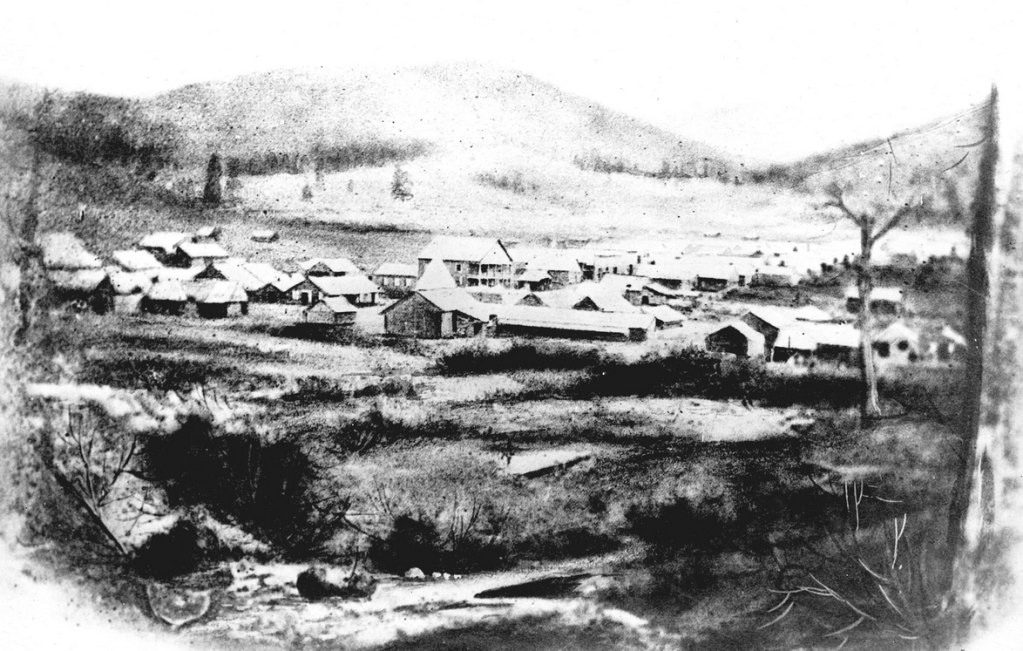

Abraham Thompson struck gold in at Thompson’s Dry Diggings in 1851. The town of Shasta Butte City would soon spring up nearby, shortly thereafter becoming Yreka, likely to avoid confusion with the town of Shasta.

Elijah Steele:

In March of that year diggings were struck on what is now called the Yreka Flats and on Greenhorn. In company with Genl. Lane I then moved from Scotts River to those diggings, where a little town was established called Shasta Butte City.

The news of the new discovery was soon spread by the traders, and the exceeding richness of the district caused a sudden and heavy influx of miners who, excited by the prospect of suddenly realizing their fondest anticipations of wealth and competency, would turn out their horses and mules on the Shasta plains and pay no further heed to them until they had either realized their anticipations or had met with disappointment from not striking it and were again in want of them to either start for their far distant homes or in search of other and to them more lucky diggings. . . .

As a consequence of the inattention of the miners to their horses and mules they frequently strayed off a long distance, and when wanted could not be found by their owners and but for the influence of Genl. Lane much irritation and difficulty would have grown out of that source, which would have involved us in a fatal Indian war.

Genl. Lane commanded the respect of the whites and had won the confidence and affection of the Indians, and at a word from him Old Tolo would send out his young men to look up any lost animals desired. Upon bringing them in and delivery to him he would award to the Indians a shirt, pair of pants or drawers or some little trinket according to the value of the animal and the trouble in finding.

This duty which by common consent was awarded to him was a heavy drain both upon his time and his means, but was performed with a cheerfulness which has endeared him to all of the old settlers here. Many times the owner of the animal had nothing with which to reimburse the Genl., and the horse was his only means of exit, in which case he never allowed the owner to go out on foot, but bid him take his animal and ride.

Yreka quickly grew into the central supply town for the entire region. It was also central to organized violence against the Shasta people and surrounding tribes. The town did more than tolerate violence, it monetized it. Following the 1851 gold strike, Yreka became the headquarters for volunteer militias who were not just protecting miners, but actively clearing the land. Merchants who benefited from the sales of supplies and munitions were often their most ardent supporters, with their businesses serving as a gathering places for the regulars.

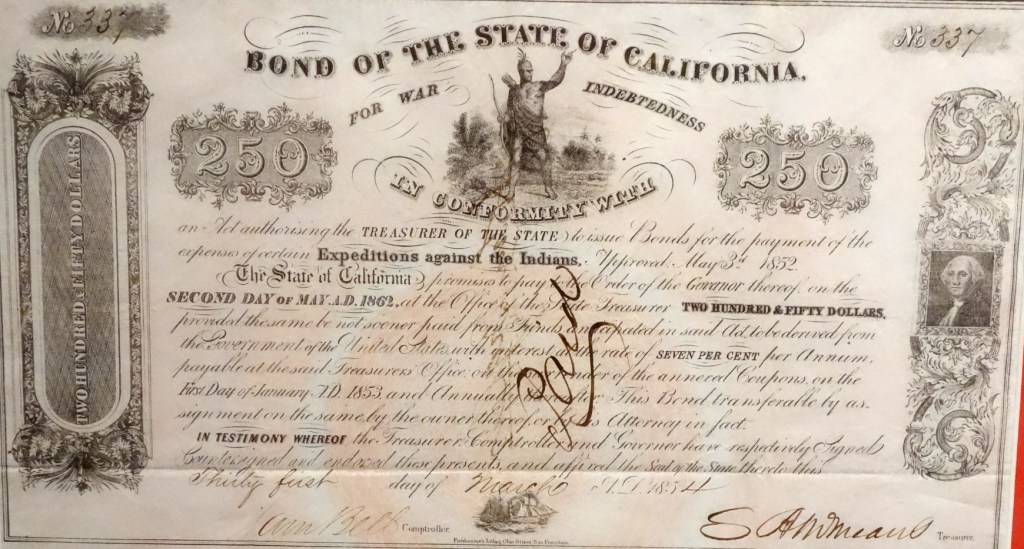

“In the early 1850s, the California legislature authorized payment for multiple expeditions against the Native Americans of California. Some scholars believe that state legislators and officials ‘created a legal environment in which California Indians had almost no rights, thus granting those who attacked them virtual impunity.’ In addition, state legislators raised up to $1.51 million to pay for state militia expeditions against California Native Americans.” – California History and Genocide

When the state of California passed legislation to reimburse these volunteer companies for their ammunition and supplies, killing Native Americans became a lucrative side-hustle for the mining community. In many northern California towns, bounties were paid for severed heads or scalps, incentivizing “hunting” parties that targeted non-combatants, including women and children, to maximize profit.

The work of river mining itself directly contributed to the starvation that forced the Shasta tribe into conflict with the miners. Streams were entirely rerouted so that their beds could be mined, and silt and debris stirred up from all the mining clogged main channels. This silt choked the gills of the salmon and covered the gravel beds where they spawned, eliminating the primary winter food source for the Shasta.

When the miners destroyed the fisheries, the tribes faced immediate famine, forced to steal the miners’ cattle and mules simply to survive. The miners then used these thefts as legal justification for punitive expeditions that wiped out entire villages.

California Governor Peter Burnett’s State of the State address, January 6, 1851 (excerpt):

Since the adjournment of the Legislature repeated calls have been made upon the Executive for the aid of the Militia, to resist and punish the attacks of the Indians upon our frontier. With a wild and mountainous frontier of more than eight hundred miles in extent, affording the most inaccessible retreats to our Indian foe, so well accustomed to these mountain fastnesses, California is peculiarly exposed to depredations from this quarter.

…there is… no reason to suppose that there has been any regular or well-understood combination among <the tribes in California> to make war upon the whites. They are all, however, urged on by the same causes of enmity, and the result has been, that at almost all points upon our widely-extended and exposed frontier, hostilities, more or less formidable, have occurred at intervals, and many valuable lives have been lost.

Among the more immediate causes that have precipitated this state of things, may be mentioned the neglect of the General Government to make treaties with them for their lands. We have suddenly spread ourselves over the country in every direction, and appropriated whatever portion of it we pleased to ourselves, without their consent and without compensation.

Although these small and scattered tribes have among them no regular government, they have some ideas of existence as a separate and independent people, and some conception of their right to the country acquired by long, uninterrupted, and exclusive possession. They have not only seen their country taken from them, but they see their ranks rapidly thinning from the effects of our diseases.

They instinctively consider themselves a doomed race; and this idea leads to despair; and despair prevents them from providing the usual and necessary supply of provisions. This produces starvation, which knows but one law, that of gratification; and the natural result is, that these people kill the first stray animal they find. This leads to war between them and the whites; and war creates a hatred against the white man that never ceases to exist in the Indian bosom.

This state of things, though produced at an earlier period by the exciting causes mentioned, would still have followed in due course of time. Our American experience has demonstrated the fact, that the two races cannot live in the same vicinity in peace.

The love of fame, as well as the love of property, are common to all men; and war and theft are established customs among the Indian races generally, as they are among all poor and savage tribes of men…

When brought into contact with a civilized race of men, they readily learn the use of their implements and manufactures, but they do not readily learn the art of making them. To learn the use of new comforts and conveniences, which are vastly superior to the old, is but the work of a day; but to acquire a knowledge of the arts and sciences, is the work of generations.

Like the people of all thinly populated but fertile countries, who are enabled to supply the simplest wants of Nature from the spontaneous productions of the earth, they are, from habit and prejudice, exceedingly adverse to manual labor.

While the white man attaches but little value to small articles, and consequently exposes them the more carelessly, he throws in the way of the Indian that which is esteemed by him a great temptation and a great prize; and as he cannot make the article himself, and thinks be must have it, he finds theft the most ready and certain mode to obtain it. Success in trifles but leads to attempts of greater importance.

The white man, to whom time is money, and who labors hard all day to create the comforts of life, cannot sit up all night to watch his property; and after being robbed a few times, he becomes desperate, and resolves upon a war of extermination. This is the common feeling of our people who have lived upon the Indian frontier. The two races are kept asunder by so many causes, and having no ties of marriage or consanguinity to unite them, they must ever remain at enmity.

That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected. While we cannot anticipate this result but with painful regret, the inevitable destiny of the race is beyond the power or wisdom of man to avert.

“The tribes of California had 18 treaties negotiated with them in 1851. Agents McKee, Barbour and Wozencraft split the state in thirds and negotiated with all of the tribes they could in a limited time. Redick McKee traveled from Sutter’s Mills (Sacramento) north, through the Sonoma areas, and up to the Klamath river, all the way to the Oregon Border. The expeditions missed many tribes on the coast and at the foot of the Sierras.” – David G. Lewis

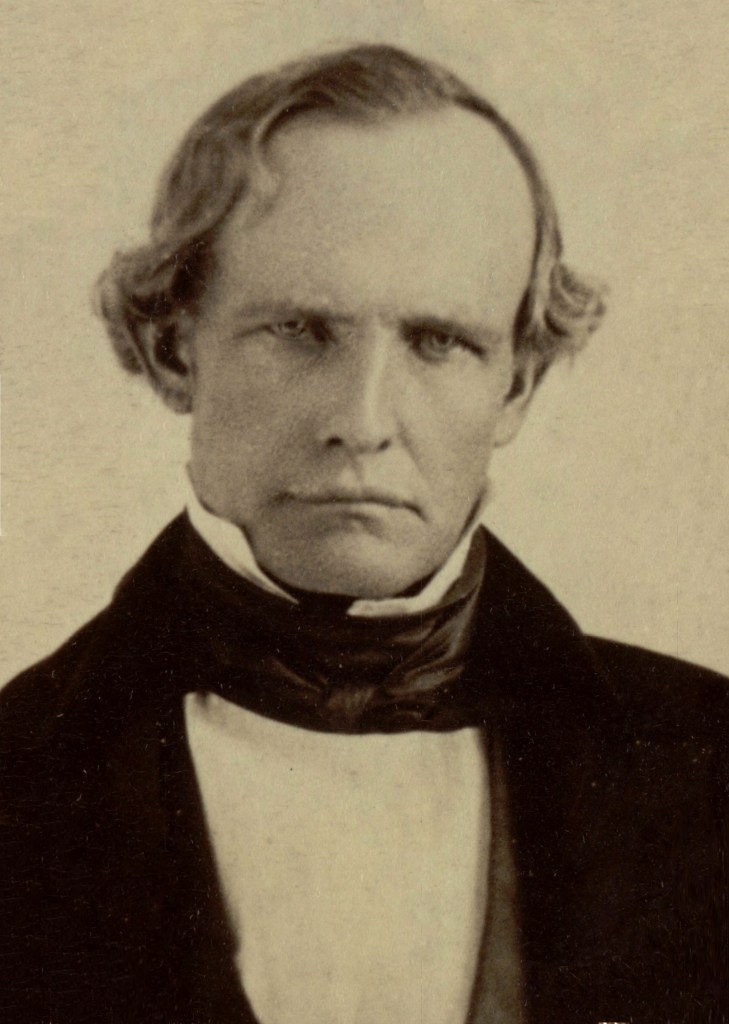

California Indian Agent Redick McKee wrote to subsequent Governer John Bigler after treaties had been signed with the tribes but were not being ratified in congress.

San Francisco, April 5, 1852

Sir: Since my last communication, I have received additional information from the northern districts which confirms my worst fears regarding the state of our frontier. It is evident that the policy of the State, as currently pursued through the local volunteer companies, is not only failing to produce peace but is the active agent of further blood-letting.

In my recent tour through the Klamath and Scott Valleys, I found a people [the Shasta and neighboring tribes] naturally docile and amicable, yet driven to the verge of despair by the constant encroachments of our citizens. These people have rights—at least the right of existence and subsistence—and yet we have spread ourselves over their country in every direction, appropriating their hunting grounds and fishing dams without their consent and without compensation.

I am aware that a strong feeling exists in the Legislature against the reservations I have established. It is argued that they include valuable mineral or agricultural lands. This may be true in part, but I ask your Excellency: Where shall these people go? If we drive them from the valleys, they must starve in the mountains or descend upon our settlements as robbers.

I must plainly state that the current system of allowing miners to organize for ‘defense’ is, in truth, a system of indiscriminate murder. No act of a white man against an Indian, however atrocious, is followed by a conviction in our courts. This impunity has led to a state of affairs where the innocent are punished for the crimes of the guilty.

I despair of seeing the peace of those settlements fully established, until the laws of the State are enforced, some terrible examples made, or the government of the U.S. send the military commandant of this division, the men and means, to establish several small military posts to protect the Indians from such attacks.

Any other policy must of necessity be one of extermination to many of the tribes. To feed them for a few years is not only a work of mercy but a matter of economy; for it is cheaper to feed them than to fight them, and the cost of one month of a volunteer campaign would more than provide for their wants for a year.

The Shastas and other associated tribes had signed a treaty in November of 1851. They agreed to give up their territory in the Scott and Shasta valleys, with the exception of a 30 mile stretch of land in the Scott Valley that would be set aside as a reservation for the tribe. The conditions of the treaty also stipulated the government would supply the tribes with food for 2 years while they began the process of cultivating the reservation lands.

However, unbeknownst to the tribes, the US Senate rejected 18 California treaties in July of 1852, after too many settlers had objected to losing access to the reservation lands. The Senate then resolved that the rejected treaties be “filed under an injunction of secrecy.” This meant that for over 50 years, whenever California tribes or their advocates asked about the treaties, the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the War Department denied all knowledge of their existence.

“The treaties went to Washington, D.C. to be forever tabled by Congress, and buried in the National Archives. They were not found again until 1907. However the tribes had negotiated in good faith and many removed to the specified reservations when asked. They expected the treaties to be ratified any day. They gave up their ways of life and began depending on the federal government for their food and safety. They saw the agents and the federal government like chiefs, and respected them and obeyed their orders and decisions.” – David G. Lewis

The Shastas, who had been promised farming assistance and supplies of flour and cattle, continued to starve while waiting for fulfillment of what they thought was a done deal. As far as the official word from the United States was concerned, there was no deal, and never had been. By 1853 the Shastas had no land to call their own, and no understanding of why the government had turned its back on them. They roamed the lands, looking for sustenance wherever it could be found.

The Starvation Winter of 1852–1853 was a near-total collapse of the supply chain that John Smith worked in.

In December 1852, heavy snow trapped the mining camps, followed in January 1853 by a warm “Chinook” wind and torrential rain, causing massive flooding that washed out the few bridges and trails that existed. Pack trains were completely cut off from the Willamette Valley and California, unable to deliver any supplies or goods.

The price of flour skyrocketed to $1.25 per pound (approx. $40–$50 today), and even then, it was often unavailable.

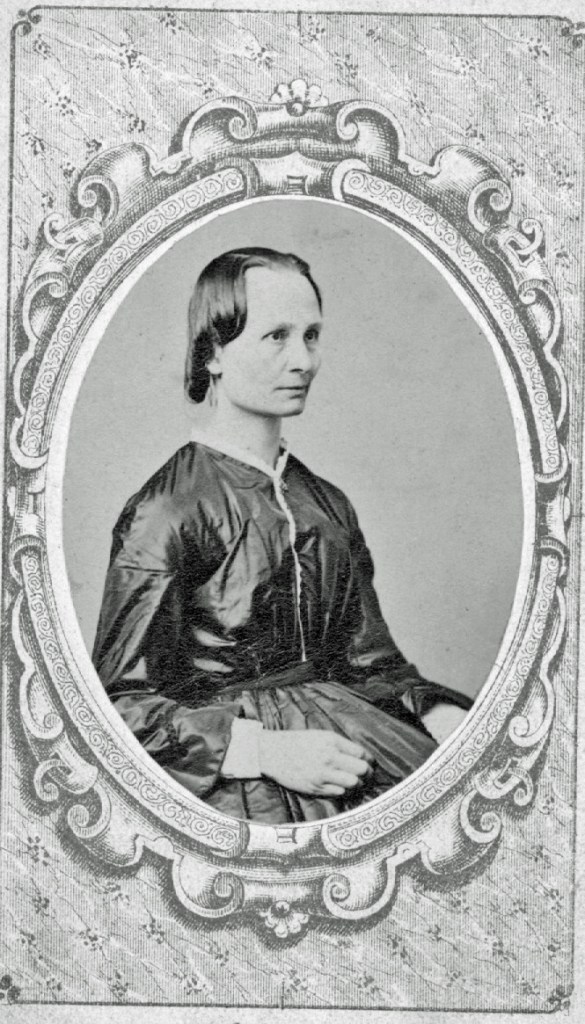

Unfortunately once again John Smith fails to mention these things in his recollections, they merely being the prelude to set up his later efforts in the settlement of Spokane County. Instead, we’ll have to turn to the diary of America Rollins Butler in Yreka during that difficult winter to get an idea of what folks were going through.

TUESDAY, NOVEMBER 30. Two weeks constant rainy weather the last of this month, with sad and duzzled [sic] spirits combining.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 15. The suffering poor are supplied by charity, or the starving cries of childhood and age would end in death. How trifling does man appear in supplying his daily wants.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 16. We have just bought 5 lbs. corn 1.00, rutabagas 15 cts., 1 squash 20 cts. lb. as the last eatables we expect to get in Yreka. Shall we starve then?

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 17. Snow in flakes like tablespoons, 1 foot fell today, requiring all cautious ones to remove the same from the roofs. The 10 building [sic] has fallen or been crushed by the pressure of the snow.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 18. Hunting stock in snow 3 feet deep. Brush is their only subsistence; two have almost perished. Drive them out to Smith’s ranch, buy some hay to feed them until the storm is over. Hay $100 per ton.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 19. Return home [from] Smith’s ranch, wading the snow water till late at night. The sun shining the first since the storm. Loved wife is not quite alone in husband’s absence. Wife would like to know who is the co., as she has forgotten.

MONDAY, DECEMBER 20. Piles of snow! Yea, verily a week cannot supply the demand. Scores are leaving this breadless valley for Shasta City, and many get frosted in crossing the mountain, but none perish that we have heard of.

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 21. Cousin Rollins returns from Rogue River Valley after an absence of 3 weeks. A garden home in prospect may it prove such to us pilgrims. But it does not.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 22. Still falling flakes and frosty breath from zero. Why should silly mortals anticipate on the future when we are so little deserving the benefits at our Creator’s hand.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 24. Hunting grass & game on Shasta River, finding neither, but feeling frosted feet. Thermometer zero. What a climate and country for the visionary.

SATURDAY, DECEMBER 25. Breakfast on squash, as usual. Killed the ox for Wilson so that [on] Christmas [we] might eat meat. $200 cake severed. Wife enjoys Christmas with jolly friend & feast the appetite & spirits.

SUNDAY, DECEMBER 26. Return to social supper with friends Mrs. Hathaway, [Yreka Postmaster John] Lintell, Rollins, an epicureal feast to all, not anticipating coffee, bread, pies &c. at wife’s house from contribution.

MONDAY, DECEMBER 27. The luminary of day has condescended occasionally to show his face, it having been hid in a mantle of clouds most of the time for two weeks.

TUESDAY, DECEMBER 28. Thaw approaching. How anxiously are thousands of people with no bread, but few potatoes, meat or wood, also vast herds of beasts, longing for the snow & chilling frost to disappear.

WEDNESDAY, DECEMBER 29. Growing warm & rainy. What a contrast do the wheels of time unroll to our view, compared with our home in Illinois one year since.

THURSDAY, DECEMBER 30. An appearance of a pleasant day for hunting. After climbing Deadwood trail with Cousin, we throw our weary limbs on the ground for a snooze.

FRIDAY, DECEMBER 31. Changeable wind, rain, sleet. Return to our home. A deer hunt indeed. All safe but the broken window. An invitation to a party at Mr. Kendall’s, but do not go as Deary is too tired to leave home.

THURSDAY, JANUARY 1. I could wish all my friends a happy New Year’s and a larger share of success, joy and happiness than they have realized any previous year. But when I hear the incessant patterings of the rain and see the dark and lowering clouds I cannot but anticipate the forebodings of evil. Families moving from the flood.

THURSDAY, JANUARY 8. Starvation is staring us in the face. We still live on meat and a few vegetables, fearing soon to be without these. Mr. Butler has gone today to get some turnips out of the river; poor bitter things they are too.

SUNDAY, JANUARY 18. Today for the first time for two months a train came in bringing flour. This will alleviate but not quite prevent starvation, as there are only twenty-five hundred [pounds] of flour.

MONDAY, JANUARY 19. Three other trains also arrived today, bringing a very little flour and very little excepting dry goods and miners’ tools. Times very hard and very little business doing.

TUESDAY, JANUARY 20. Glorious news–here comes another train bringing 8,500 lbs. of flour. Business revives; men look happy & cheerful. Look out, here comes the express; what a general rush to the office to get the news that has been withheld 9 weeks. This day will long be remembered by the people of Yreka, for it is a memorable day.

WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 21. People are once more anticipating good times. Quite a train of our citizens have started to Shasta City today, most of them on a speculative trip. Fine and pleasant weather &c. Heard from our friend in the States yesterday; all well.

This starvation winter would be the end of the line for John Smith’s prospecting days.

Leave a comment