At the end of the 19th century Gdańsk traded in the western half of its obsolete moat for a modern transit corridor, capped with a neo-renaissance train station that iconically sets the vibe of visiting the city.

Efforts in the 1990s to turn the central hall into a two-level mini-mall were removed 25 years later, after which an extensive course of updates and restoration began to bring the station back to its full spacious glory. This process had just been completed shortly before my arrival.

Surviving World War II burnt but relatively intact, the greatest threat to the old station came in the 1960s when serious consideration was made to demolish it and replace it with a modern building. Thankfully it was saved from such a brutalist fate, although the interior suffered numerous indignities over time.

Today it’s been brought back to something approaching its original splendour, and makes for a classy welcome to the city, a public palace for every man.

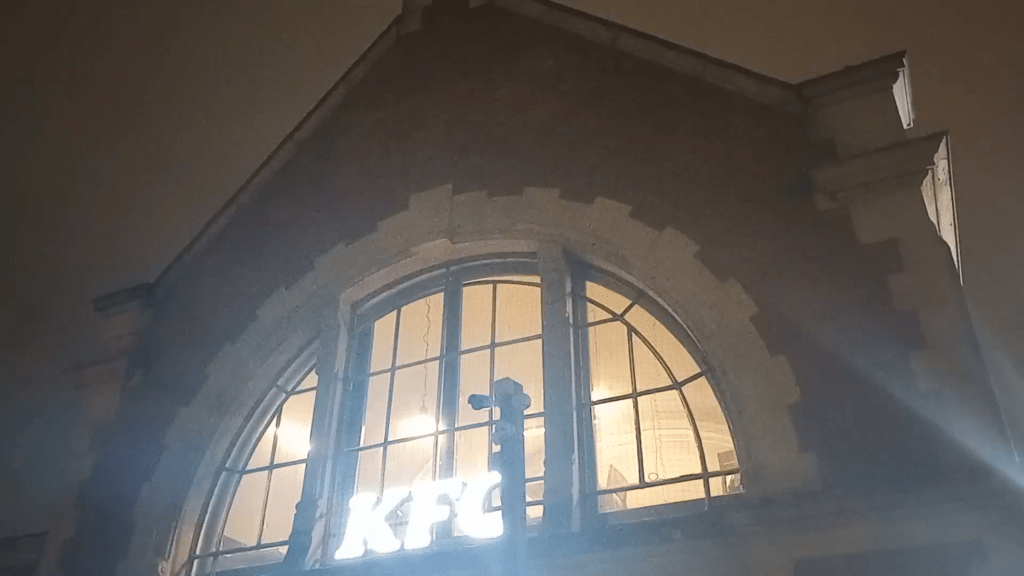

The highway has become the moat of the modern world. But don’t worry. If you arrive hungry there’s an adjacent KFC in the same ornate style. Smacznego!

The 16th century Highland Gate marks the point where you would’ve crossed the moat to enter the old city.

Beyond it stands the Torture House. Built on the original 14th century gate, it was transformed into a prison with multiple torture chambers in the 16th century.

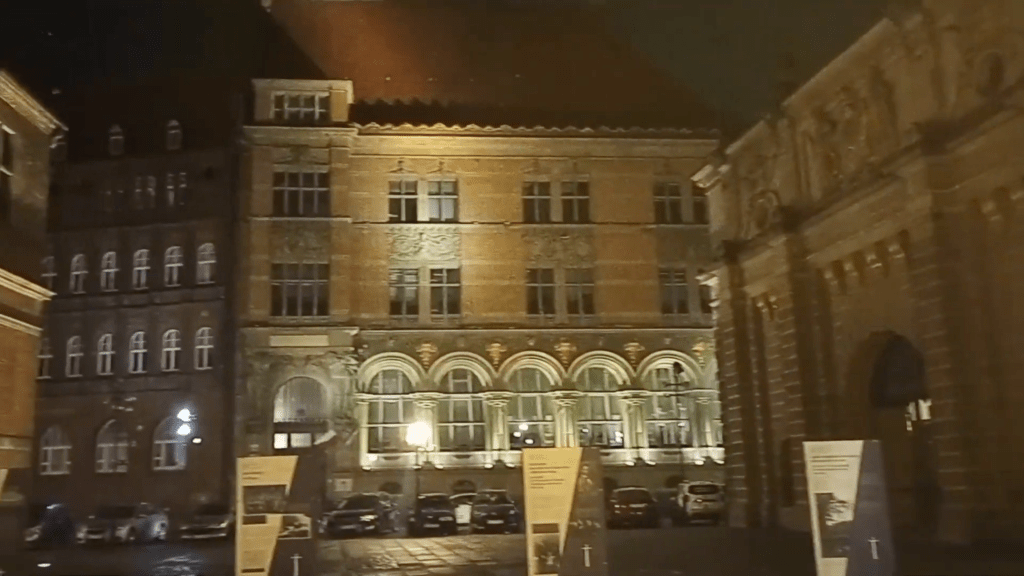

The Bank building was constructed nearby in 1895. Its neo-Renaissance style blends well with the older architecture, although it is still awaiting restoration to its original pre-war splendor.

It took the place of the old fortifications that were built around the moat, prime real estate in the heart of turn-of-the-century Gdańsk.

Stepping onto the famous Long Street, the old city’s vibe can’t help but sweep you away. Rows of classic townhouses reflect the unique intermixture of cultures that grew up in Gdańsk’s port-town setting.

With the old city 90% destroyed during WWII, many of these had to be rebuilt from the ground up. With shallower depths to create larger courtyards, they were often built with a single apartment spanning across the width of 2 of the original buildings, but still made to appear from the front like two old buildings side-by-side.

The Main City Hall was built in the 14th and 15th centuries, with the tower completed in 1488. WWII would claim the top of that tower, and the overall damage was extensive enough to require 7 years to repair after the war ended.

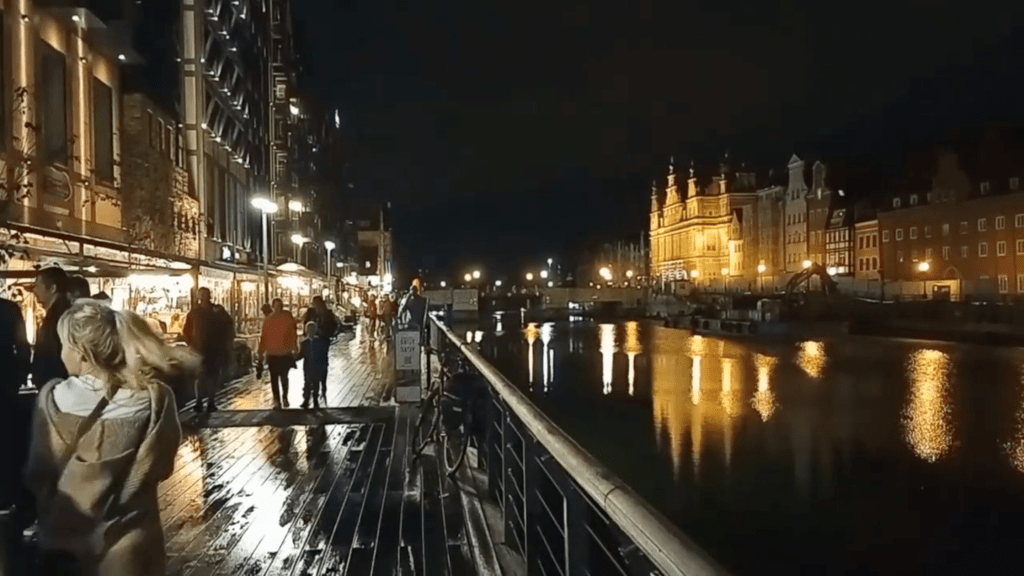

The Long Street opens out to the Long Market, Gdańsk’s unique central plaza, an elongated town rectangle rather than a square.

The fountain of Neptune that greets you is classic, an iconic symbol for Gdańsk like the mermaid is for Warsaw. Welcoming you to the sprawl of the plaza, there’s something about that statue with the Baltic Sea air that really completes the spell.

As one grand parade route, the streets are known as The Royal Way. Take a stroll and give yourself the royal treatment. The grand promenade is enough to make anyone feel a kind of special privilege to be there. Pass through the 16th Green Gate, designed to be a royal residence, and you’ll start to see what this wealth was built on. Maybe you’ll catch a musical act on the way through.

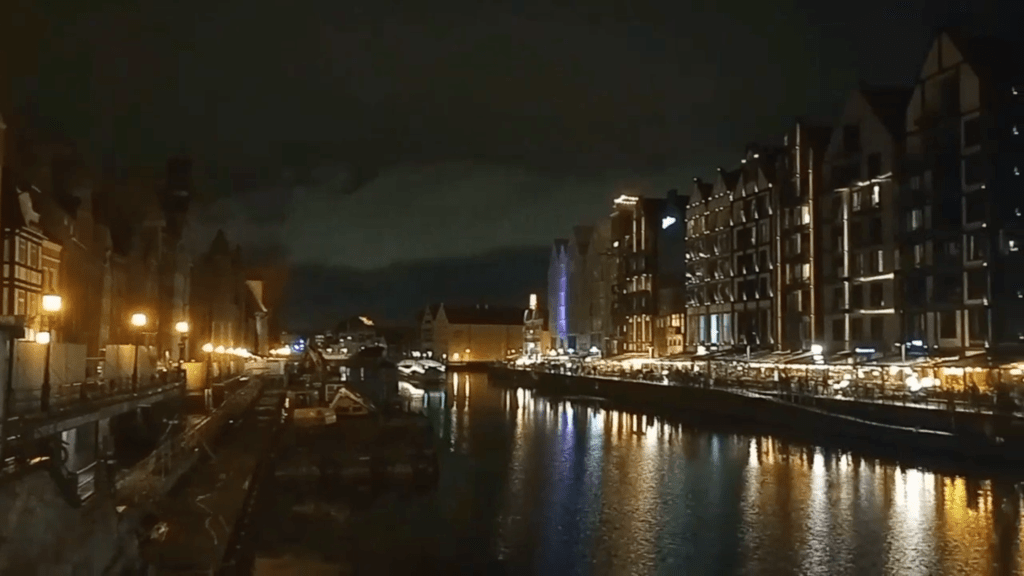

“Whoever controls Gdańsk is more the master of Poland than any King reigning there,” Prussian ruler Frederick the Great observed in the 18th century. That regal value is immediately apparent when you emerge at the heart of the old port, with its river connections running directly to the Baltic coast and deep into the heart of Poland.

The bottleneck of Baltic trade in Central Europe, Gdańsk had long operated with a great degree of autonomy between the Polish and Prussian kingdoms. That ended when it was annexed to Prussia for over 125 years.

After WWI it was seen as too indispensable to both Poland and Germany’s interest for either country to have exclusive control. Although the population was 90% German, the city was still intrinsically tied to Poland’s shipping corridor.

The Free City of Danzig was half of the compromise; the other half was a corridor carved out for Poland to have its own independent access to the Baltic Sea, from the coast where Gdynia was built, up to the Hel Peninsula, cutting up to and around Danzig. German Nationalists claimed it was a gaping open wound across their country, with East Prussia cut off and isolated from the rest of Germany.

Poland was granted special rights in the management of Danzig in order to ensure its sea access, including control of foreign relations and responsibility for the city’s defense, but the governing German-majority would constantly vote against Polish interests. In 1933 the senate came under control of the local Nazi party, who abolished democratic procedures and overtly aligned the city’s Policies with Berlin.

Hitler began launching his propaganda campaign to justify German annexation of the city. He claimed that Danzig and the territories of the Polish corridor owed their entire cultural development to Germany. In the months leading up to war he made demands that included the immediate annexation of Danzig to the German Reich, along with their own transit corridor across Poland’s coastal corridor.

Poland’s refusal of these demands, recognizing them as the classic German recipe for total domination of Poland, became the pretext for Nazi Germany to prepare its invasion.

The scars of the war that followed extend to some of the most idyllic locations of Poland. Nowhere is this more true than Hel, the little 22 mile long Cape Cod-esque peninsula of coastal Poland.

Earlier that summer the bus to Hel became route 669. If it had still been 666 I would have been compelled to catch it. Instead, I eventually caught up with a train, after riding the bus a mile past the train station up the highway. So much for good intentions.

Now a scenic destination getaway, Hel has deep military roots back to the 1920s, which only deepened during WWII.

I figured my best bet to explore this history and experience the scenic beauty was to rent a bicycle in Jurata and then return it in the town of Hel, at a related rental location.

This ultimately worked out quite well, although the lack of suspension on the bike made for a rough ride at times.

Cutting down from the main road towards the harbor side of the peninsula, a much better paved bike path takes over and reveals the seaside getaway nature of the area, proving that early fall is still a wonderful time to visit.

The Jurata Pier stretches out invitingly, making me wish I’d had a bit more time and a fishing pole with me.

The peninsula is made entirely of sand, with its contours regularly reshaped by winter storms.

The winds off the coast of Hel prove just as alluring as the waves, with parasailing a popular past time, and windsurfers making use of Jurata’s boardwalk beach as a perfect point to set sail from.

A row of small catamarans shows the endless ways one can harness wind and water to escape Hel’s shores.

Rows of bicycles along the path attest to my chosen transportation method on land being equally popular.

I caught up with another cyclist leaving the beach and we made our way back inland. Slowly, but surely…

The bike route cuts across the highway to some merciful dirt trails that wind hypnotically through the trees.

No longer a one-way path on either side of the road, you’re now on a two-way cycling highway, with steady traffic in both directions.

At one point the path crossed over the main train line, but it was the narrow gauge tracks coming together in a V that really fascinated me.

I remembered having a dream once about identical looking old tracks, and tried to figure out what this could mean.

One fork of the rails went right across the bike path, while we paralleled the other tracks for a stretch before they turned off into the trees.

I had to keep going and see where this would take me next, looking for some further sign as to where the tracks could lead as they disappeared from view.

I continued on past families resting on the side of the path. We were only about a mile away from Hel at this point. Before I found myself diverting towards some ominous destination, with anti-tank barriers sternly lining the path.

Yes, folks, War is Hell, and you’ll find out all about it at Hel’s numerous museums and historical destinations. Once the center of thunderous, heated battle, the big guns now sit cold and silent, relics of war relegated to a big kid’s playground today.

With a narrow gauge railway running almost the entire length of Hel to move munitions, troops and supplies between numerous fortifications, this train proves it’s the Little Engine that Could.

The Polish defenses deployed a variety of guns and canons, with the four biggest guns firing a 6 inch shell 16 miles. They would do significant damage, but prove to be no match for Nazi Germany’s superior firepower. After a month of intense fighting, Polish forces finally surrendered.

The impressive bunker at the naval defense museum was part of a battery of 406mm guns installed by the Nazis after conquering Hel. Capable of firing a 16 inch shell 35 miles, these guns were able to take on on the biggest battleship. In fact, they were originally designed to be mounted on battleships.

Approaching the town of Hel, past a park dedicated to the work of local carvers, the sense of the energy being stirred by some ceremony becomes undeniable. Hel is positively buzzing! What should be there to greet you on this sunny last day of summer?

A crowd has gathered around some sort of parade at the edge of town. Law enforcement officers have cordoned off a controlled perimeter.

Why, it’s a military ceremony! Probably in remembrance of the Invasion of Hel. It could just be soldiers returning to the Peninsula after exercises outside the country. At this point attempts to define the display remain inconclusive.

Whatever it is these brave boys are doing, they seem to be wrapping it up. With the largest military in Europe, Poland stands today as a bulwark in NATO’s defensive line. The soldiers here representing Poland’s armed forces execute their maneuvers with grace and precision.

Venture beyond the borders of town and the traces of war become unavoidable. One little bunker has been set up as a historical recreation of the Polish defenses, with its own vintage bicycle and anti-aircraft gun, seemingly ready to take on the next invasion.

Polish anti-aircraft batteries put a decent dent in the Luftwaffe during the battle of Hel, knocking around 50 Nazi planes from the sky.

Other bunkers are just gutted tunnels littered with debris to trip over in the pitch darkness, eerie reminders of how deep the defenses are woven into the peninsula – far deeper than this explorer dared to venture.

Remains of gun embankments sometimes still feature ruined hunks of hardware left behind. Pointed towards the Baltic coast, these defenses would be set upon by sea and by air, as the Nazi war machine unloaded the devastating force of its advanced arsenal upon the small peninsula.

Yes folks, Hell was unleashed on Hel. Today the trees have grown around the old control towers; with their defensive purpose no longer relevant, it’s the stories they still communicate that provide them with purpose today.

If these concrete walls could talk… ah but even in silence they tell a compelling tale.

Thankfully, Hel isn’t all war and death. In town I grabbed some delicious herring from a food truck and sat down to enjoy the seaside view.

Just be sure you bring some cash to Hel. Half the places don’t take cards – usually the best places.

The large domed building on the pier is the terminal for the ferry that goes to Sopot and Gdańsk. I’d hoped to take it back that day, but I watched the last ferry leave and softly sighed.

I could have gotten some awesome ice cream from a bear in the woods, but because of not having bucks on me I missed out and had to settle for soft-serve by the sea. Still pretty satisfying, just be prepared, if you’re a yank like me, to be shocked by the richer, non-acidic taste of European chocolate.

I went to find the bike return spot, and the couple that had rented me the bike swung by in a box truck and picked it up.

The carvings that welcomed me to Hel gave me a cheery departure.

Yep, it sure is nice to go to Hel this time of year.

I enjoyed the fiery sunset as I traveled back down the peninsula.

After listening to a woman playing some Ukrainian folk songs on accordion at the train station, I took a minute to admire a beautiful, tragic sculpture, dedicated to Gdynians displaced during WWII.

It shows a mother and her two children fleeing with a cart laden with their meager belongings, while their dog sits and looks on longingly, wondering when they will be back.

Perhaps never. Just the look in everyone’s eyes is heartbreaking, dog included.

I caught a fuzzy picture of a guy sitting next to the dog, making a good stand-in for the missing patriarch of the family, like a soldier or ghost returned from the war.

Welcome home.

Leave a comment