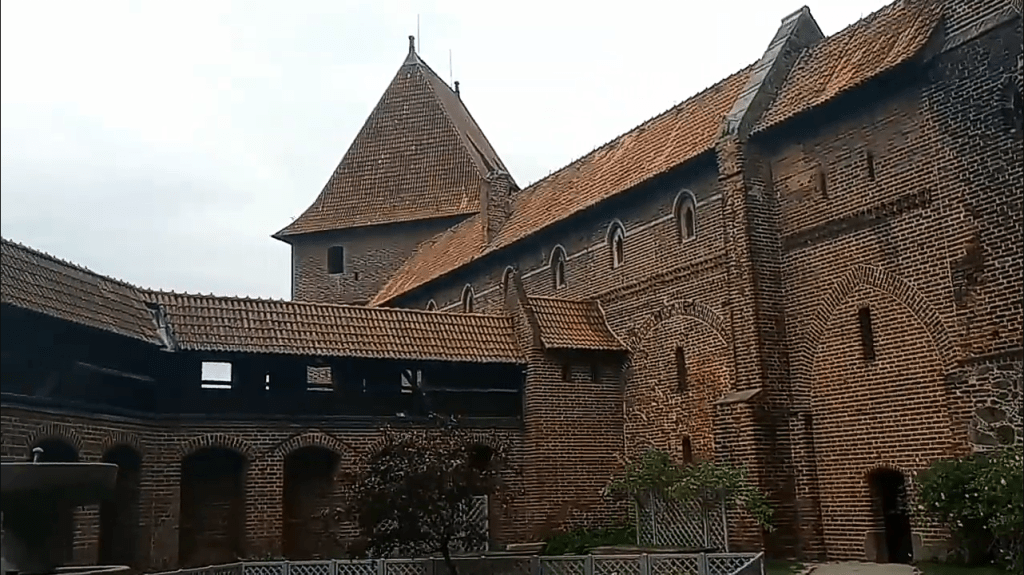

Roughly 25 miles south of the Baltic Coast, Malbork Castle rises mightily from the banks of the Nogat River.

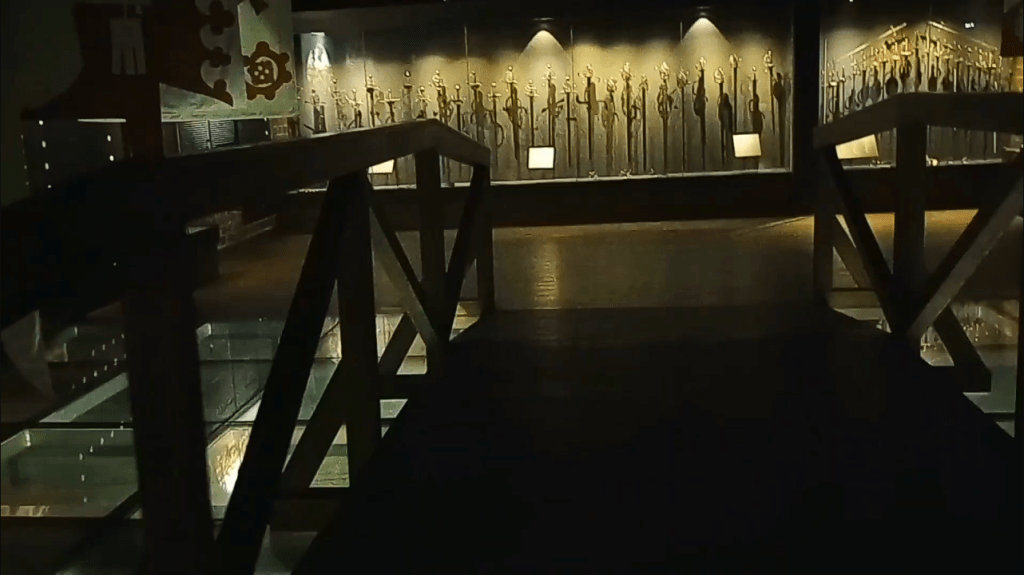

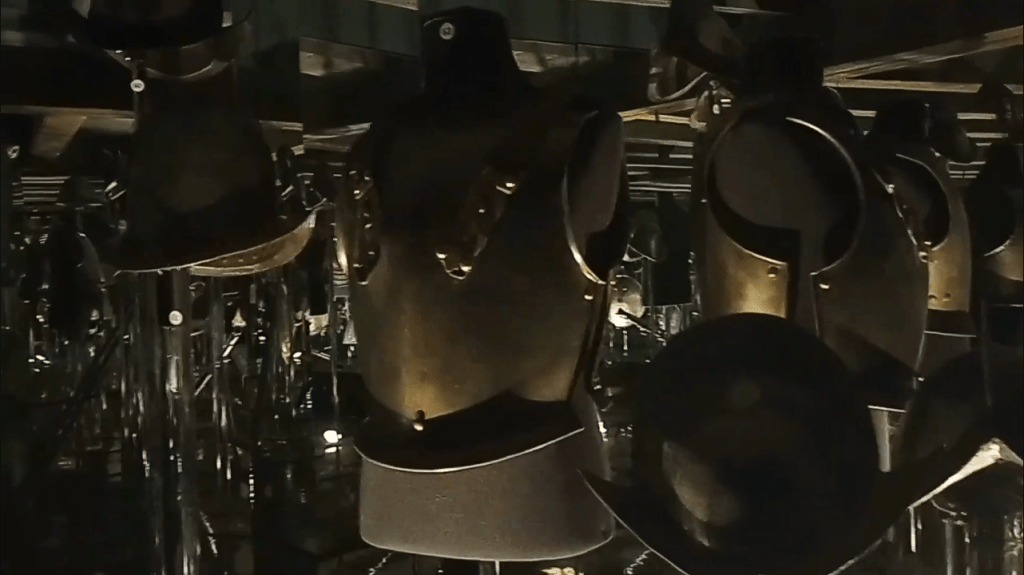

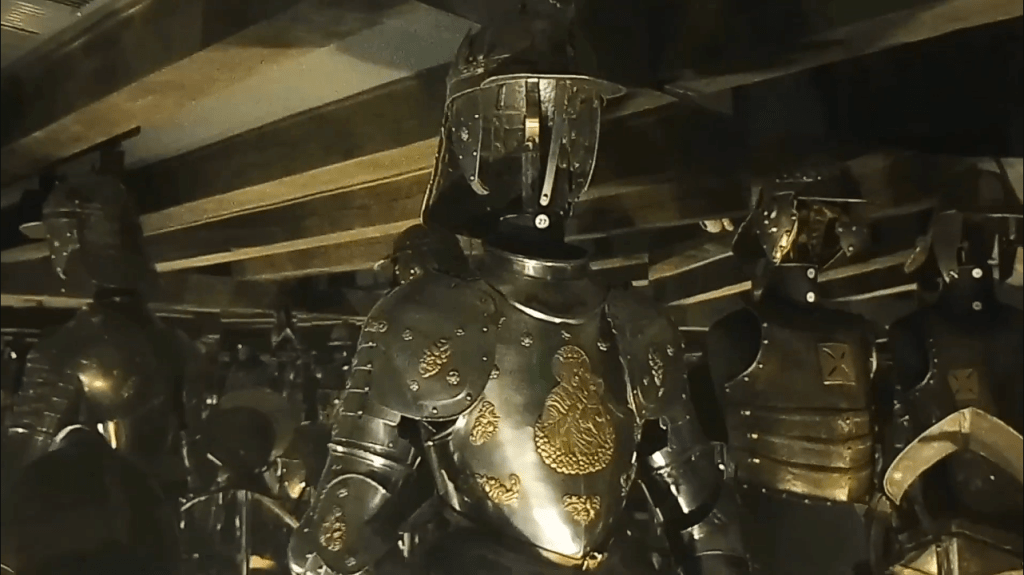

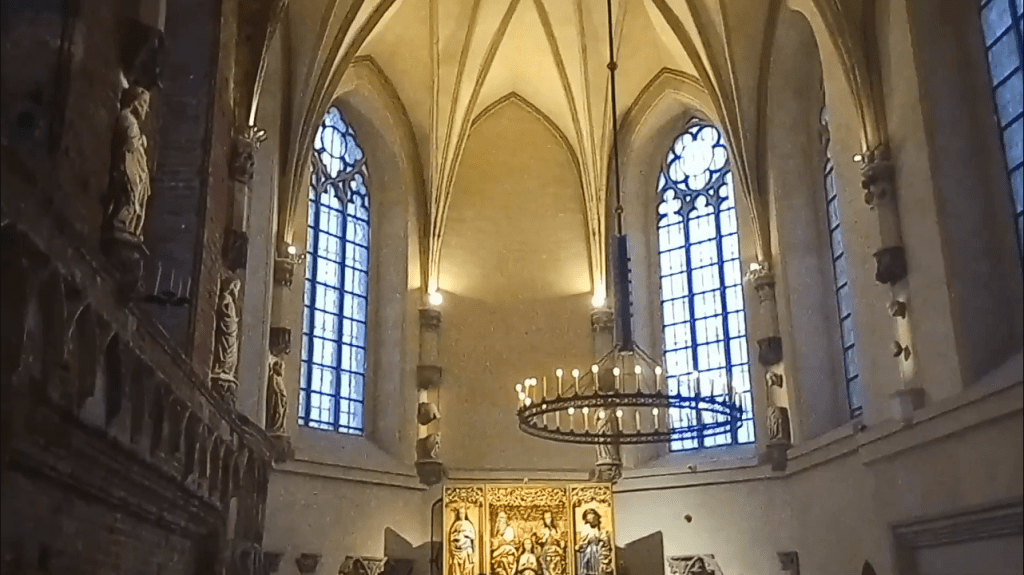

The largest brick castle in the world, the formidable 52 acre fortress stands as the grandest monument to the Order of the Teutonic Knights, and the power they once held.

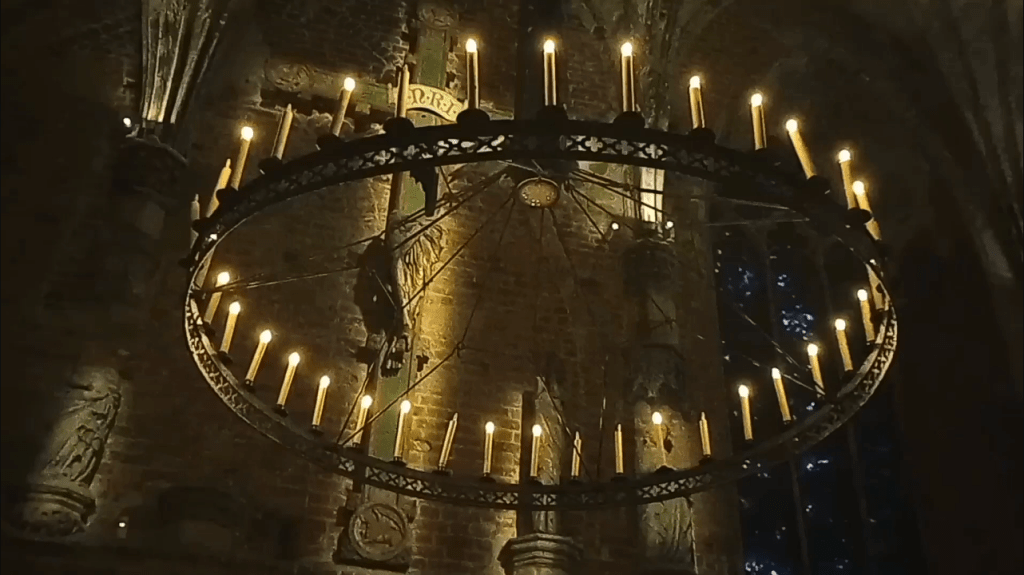

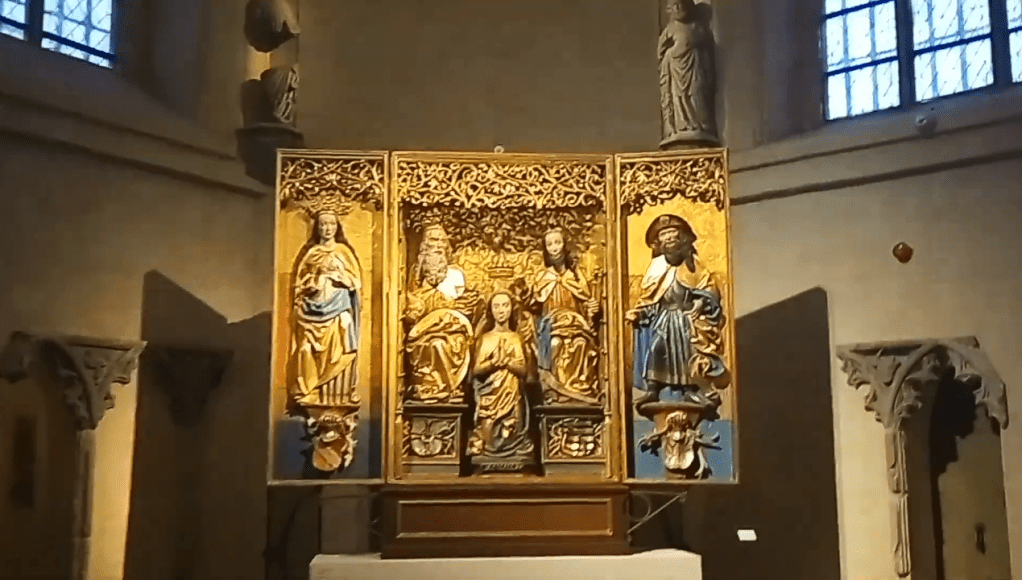

The knights, who dedicated their service to Saint Mary, named the castle Marienberg, the “Fortress of Mary”.

Gazing on its vast red brick walls, its immense scale makes you start to second guess yourself, trying to fit it into a more manageable frame of reference for your mind to process. I mean, no one would possibly build a Gothic fortress *that* big… you must just be delirious from your travels.

By the time you emerge from its labyrinthine interiors, more delirious than ever, you’ll know for sure that your first impression was correct.

The castle dominates and defines the town of Malbork, with most of the old town destroyed during World War 2. In its postwar rebirth it was decided to focus restoration efforts solely on the castle, which had been more than 50% destroyed. What rubble remained salvageable from the devastated old town was largely hauled away to be used in the reconstruction of Gdańsk and Warsaw. While it was a noble, worthy sacrifice, you can’t help but wish some semblance of the old town that grew up beside the castle had been preserved.

Construction of Marienberg began in 1276, 50 years after the Order had first come to Poland at the behest of Duke Konrad of Mazovia. With little opportunities left in the Holy Land following their part in the Crusades, the order accepted the Duke’s appeal for protection against the Pagan Slavic tribes to the east.

The Order had just spent 14 years under a similar arrangement in the Kingdom of Hungary, defending its south-eastern frontier. As they successfully dealt with the threat of invaders there, they also began to bring in Germanic settlers to farm the lands.

Becoming more and more expansionist with their efforts, the Order began to conceive of themselves as rulers of a new land, no longer on a defensive mission but rather one of conquest – conquest in the name of God, of course. The order began to claim and fortify the frontier they pacified. Needless to say, this didn’t sit well with the King of Hungary, nor did the order’s mistreatment of Hungarian settlers. Things finally came to a head in 1225, with Hungarian military forces driving the Knights from the land.

Duke Conrad thought he would be able to maintain more control over the Order’s efforts in his land. Rather than asking them to come as a temporary presence expected to take care of business and then depart, he granted them the Chełmno Lands to establish their regional base. He assumed this grant would be enough to pacify the Order’s ambitions, that they would gratefully remain his loyal subjects. He would quickly find out how wrong he was, which was about as wrong as he could be. But he would also witness how brutally effective they could be as a military force under his command.

The Teutonic Knights proceeded to violently convert the pagan tribes to Christianity, or, if that failed, they would simply annihilate them. This was largely the fate of the original Slavic Prussian tribes, their name later adopted by the Germanic population that replaced them.

It was because of their religious mission that the Teutonic Order was able to gain the Golden Bull of Rimini from the Holy Roman Emperor, which declared that all lands conquered by the Knights would come under control of the Holy Roman Empire. Duke Conrad was infuriated by this back-door move, which shifted the Order’s allegiance away from him to the Emperor and the Pope. It was just one of many problems he was facing holding his lands together, while the Order’s power continued to grow. The Pope, seeing the Knight’s conversion effort as a new Holy Crusade, confirmed their rights to the territory they conquered.

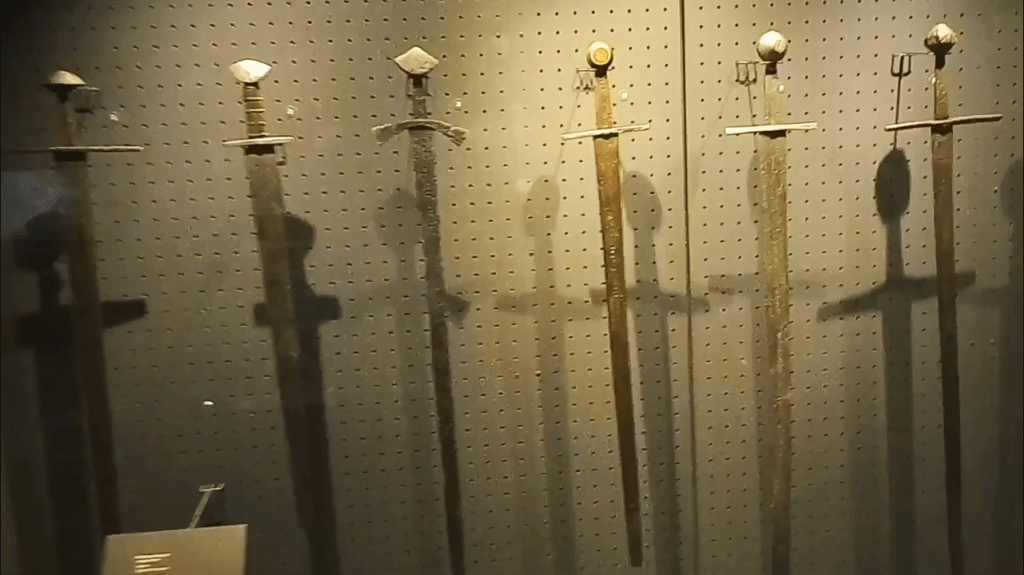

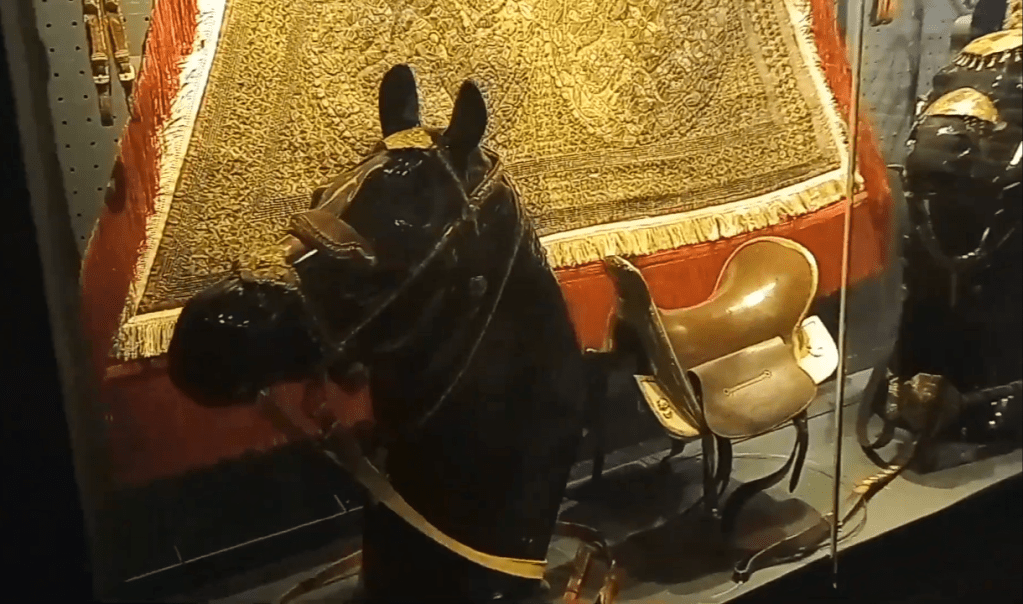

Religious influence was not all the Order found itself wielding. With their territory extending to the Baltic Coast, they were able to monopolize the Baltic amber trade. This brought tremendous wealth to the Order as their cities of Danzig and Thorn became dominant trade centers.

The battle to convert the Pagan Lithuanian tribes, Europe’s final holdout to Christianity, continued to legitimize their religious cause within the devout Polish Kingdom, despite deep concern about the growing economic and military influence of the order.

The Knights, who had all taken vows of poverty, saw it as their holy duty to bring a kind of theocratic order to the region. The fact that incredible wealth was now flowing into their coffers just happened to be a major bonus. If the lessons of the Holy Land had taught them anything, it was to seize such opportunities to survive as a vital force for Christendom, for it was not every day that God opened such doors.

The delicate balance between Poland and the Teutonic Order was destined to crumble. Once the Lithuanians finally succumbed to the relentless crusade to convert them, the Knight’s religious mission ceased to be a legitimate pretext for their presence. Their rising power found the Order in increasing conflict with the growing Polish Kingdom. No longer a group of duchies vying for regional power, Poland now found itself united in the common cause of defending itself from the Order’s seemingly limitless quest for power.

In the summer of 1410 this conflict would explode in one of Medieval Europe’s fiercest clashes at the Battle of Grunwald. Poles and Lithuanians, now bound together in an alliance against the Teutonic Knights, inflicted the Order’s first truly devastating defeat at the brief but bloody battle.

Estimates of the number of combatants present varies somewhere between 27,000 to 66,000. When an epic film of Polish author Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel The Teutonic Knights was produced in 1960, it used 15,000 extras to recreate the great contlict. In the end the charging warriors and horses kick up so much dust it almost swallows the entire battle, leaving the spectacle largely incomprehensible. Close-ups present the combatants engaged with the audience itself, finally brought down by a bevy of swords and spears thrust forth directly from the crowd.

Compared to paintings I’ve seen of the battle, which clearly and cleanly depict each fighter within a sea of warriors in a sort of God’s eye freeze-frame, the film perhaps better represents how fleeting those moments of clarity were within such waves of chaotic violence.

The Battle of Grunwald lasted just one day. When it was over the remainder of the Teutonic Order’s forces tucked tail and beat a hasty retreat back to Marienberg. Their Grandmaster, along with many other leaders, had fallen in the battle. The entire structure of the monastic Order was effectively decimated.

Polish and Lithuanian forces took their time pursuing the fleeing Knights, instead mobilizing their efforts to take control of other Teutonic strongholds throughout the region, most of which surrendered without resistance.

By the time a siege was mounted against Marienberg, the Teutonic Knights had thoroughly fortified the stronghold. The attackers were not prepared for such a well mounted defense, expecting surrender to come as swiftly as it had elsewhere.

After nearly 3 months of bombardment, the siege was lifted. Polish-Lithuanian forces returned home, leaving garrisons in the fortresses they had taken, which were then mostly retaken by the Order.

While Marienberg had been under siege, the propaganda efforts of the Order went into overdrive, looking to strengthen their forces with “guest crusaders” from the Germanic lands of the Holy Roman Empire.

They painted the Polish-Lithuanian union as an “unholy alliance” of supposedly Catholic kingdoms with Orthodox Christians from the eastern borderlands and Muslim Tatars. The Order were defending the Christian frontier against heretics and infidels, they claimed. They contested the very legitimacy of the Polish Kingdom.

More than 10,000 reinforcements rushed to the Teutonic lands, convinced barbarian hordes being kept at bay by the Knights were about to break through and continue rampaging into the Holy Roman Empire.

With this replenishment of their forces, the Order felt that the tide was about to turn in its favor. However, despite their renewed strength they suffered another major defeat at the battle of Koronowo, with the young, undisciplined recruits proving no match for the battle hardened Polish forces. The Order’s military power now truly crippled, the two sides agreed to negotiate.

In 1411 the Peace of Thorn was signed, imposing a heavy financial burden upon the Order, now diminished in both its ranks and its power. The roughly 250 out of 500 knights that had survived the battles had mostly been taken prisoner and were now being held for ransom. Regaining the freedom of their leadership proved to be enormously costly.

They were also forced to hire mercenary troops to defend their territories, finding it impossible to replenish the forces lost in war through new recruits, which only added to their financial woes. While the Bohemian and Silesian mercenary armies that now took control of the defense of Teutonic territory proved amply worthy of the task, their lack of motivation beyond a promise of payment would have major consequences.

The Order spiraled deep into debt, confiscating wealth from churches, and levying increasingly steep taxes upon the lands under its control to make the payments.

Eventually, the decline of the Order, coupled with the increased tax burden, led to the foundation of the Prussian Confederation in 1441, standing in defiance of the Order on behalf of Prussian merchants. This opposition would decisively defeat the Order at the end of the 13 Years War in 1466, bringing their influence in the region to an end.

Marienberg wouldn’t be surrendered at the end of the war, it would actually be lost 9 years earlier. The mercenaries who defended the castle, having back pay owed to them that would add to something like $50 million today, and with Marienberg itself the promissory collateral they held in lieu of payment, just turned around and sold the castle to Poland’s King Casimir IV for the wages they were owed.

It would be the end of the Teutonic Order’s nearly 150 years headquartered in Marienberg. The castle became one of the Polish royal residences, now known by the Polish name Malbork. From 1656 to 1660 it fell under the control of Swedish forces during their “Deluge” of the country, but otherwise it would remain under Polish control until the annexations of 1772, which saw it become part of the Prussian Empire – once again under Germanic control.

Used as both a barracks by the Prussian army and a poor house, by the turn of the 19th century serious consideration was being made as to whether the old, well worn castle was worth saving or should simply be demolished. Thankfully, engravings that were produced as part of this evaluation caught the public’s eye, and soon the castle found itself celebrated as a vital piece of Germanic heritage.

After being utilized by Napoleon and his army during his campaigns in Central Europe, serious restoration work finally began on the castle in 1856, continuing in waves until the outbreak of World War 2. After the damage it suffered in battle, more extensive work was undertaken to bring us the tremendous restoration of the fortress that stands today.

In some places only fragmentary features of the statues of the saints remain. Perhaps they reflect the fragmentary nature of the Teutonic Order’s legacy. The power they once wielded as a collective now has no embodiment left in our world, merely the hint of a hand here or a face there, somehow mounted without a body to bear the load, held aloft as a reminder of what once was.

As the Order’s influence dissolved as a body in the 16th century and with it the dream of the great Teutonic state, the most powerful members found a backdoor to preserve their social positions by converting to Lutheranism. This allowed them to secularize properties that the Order had held in the name of the Catholic Church and acquire them as their own assets, becoming a part of the Prussian nobility as wealthy land owners. Their final religious scheme for advancement became the abandonment of Catholicism entirely.

The new class of German nobility that rose up would have a profound, lasting impact on Germanic society. An aristocratic, militaristic social order, constantly focused on protecting Prussian borders, its power and influence would be felt most profoundly by the world as the horrors of the First World War were unleashed by the Germanic state.

The Prussian Empire had taken on the Teutonic Knights as their great heritage. The Nazis would also do the same. Their defeat brought with it a reckoning of those deep-rooted ideals of duty, discipline, and nationalistic loyalty that still find reverberation in our times.

Perhaps it’s the scars of Malbork that show us the futility of building walls and thinking they will protect us from our own worst tendencies, rather than imprison us with our shadows. Let’s hope for the sake of the children who play around (and even on) those walls we learn that lesson before it’s too late.

On my way back to Gdynia I took a trip to neighboring Tri-city Gdańsk.

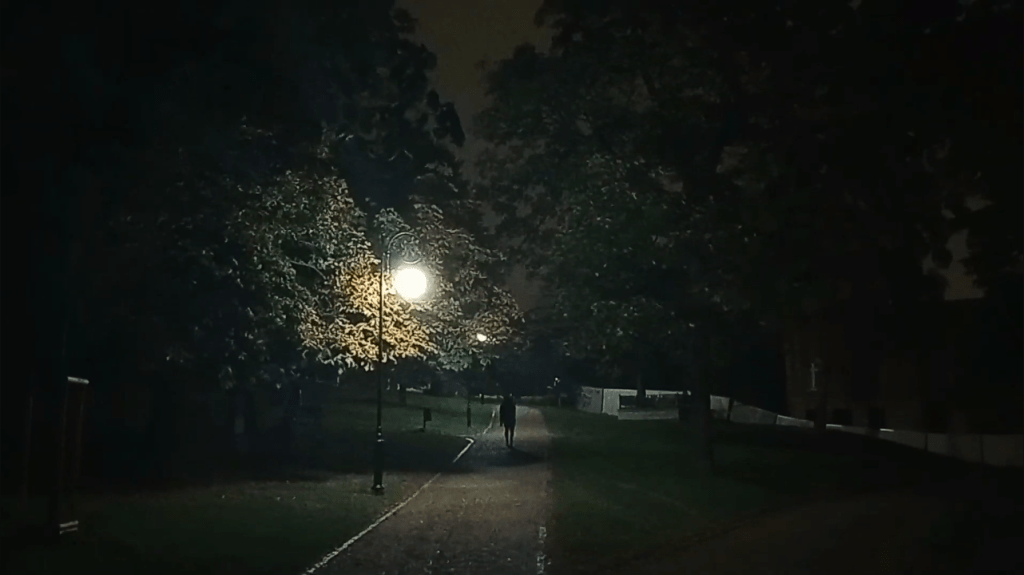

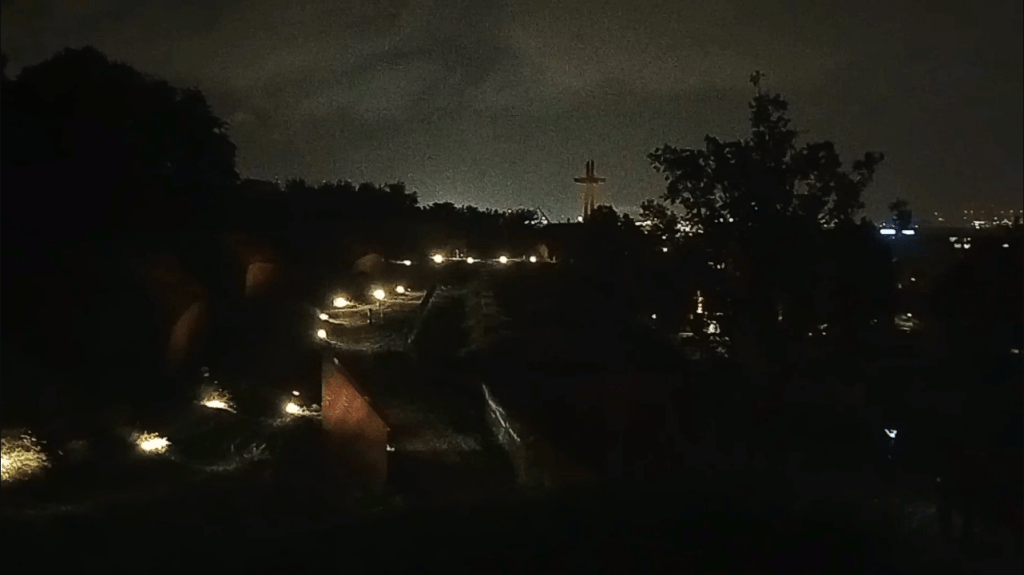

Despite the weather turning pretty dark and wet I repeated a maneuver I’d stumbled upon during my brief visit the previous year and made my way up Mt. Gradowa to get a good look down at the city.

The hill was first fortified in 1655, and further fortifications took place in the 19th century. Medieval coins dating back to the 1300s were discovered when excavation was done for the construction of the Millennial Cross in the year 2000. It stands overlooking the port city with a modernist but earthy flow.

Perhaps that is the best way to describe the energy of Gdańsk. With its big Ferris wheel spinning and trams cruising past centuries of history, the city moves as smoothly and proudly as a modern metropolis, but with its layout having a classical logic to it closer to a magic spell than a simple grid.

Gdańsk would grow into the region’s most important center for Baltic trade after King Mieszko I, Poland’s first Christian king, annexed the settlement in 980, constructing a fortress where the Vistula and Motława rivers meet.

It was this growing importance as a trade hub that first brought German merchants to the region towards the end of the 12th century. Establishing their own Germanic colony, by the next century they would find themselves vying for control of the region when the dynasty of the ruling Polish duchy came to an end. In alliance with Brandenburg forces, they would briefly take control of the town.

Polish forces under siege in the old fortress, seeing no other choice, reached out to the Teutonic Order, who were also vying for control of Gdańsk. The Teutonic Knights freed the Poles but then proceeded to take control of the town, massacring both Brandenburg forces and townspeople alike. This act would cement the hostilities between Poland and the Teutonic Order for the remainder of the Order’s existence.

Now known by its German name of Danzig, Gdańsk would remain under the Order’s control until 1466, when it would be incorporated into the Kingdom of Poland after the Second Peace of Thorn. Still maintaining a majority Germanic population, it would become part of the Prussian annexation of Poland in 1793.

At the end of the first World War it would find itself, not integrated into the new nation-state of Poland, but rather a free, independent city, considered too vital to trade to be under any one nation’s control.

It wouldn’t remain free for long…

To be continued…

Previously:

Leave a comment