After 2 days and nights in Warsaw I packed my bags and headed out in the morning.

Looking over my tram connection stood the Parish of Saint James, with Poland’s iconic Black Madonna of Czestochowa gleaming proudly from its facade.

Construction of the church began in 1911. Poland at that time was a memory of a nation, its lands still claimed by the neighboring empires that had carved it up in the 18th century. These empires soon found themselves pulled into conflict when the first world war erupted across Europe. When it was over, Poland would find itself reborn as a modern, independent nation.

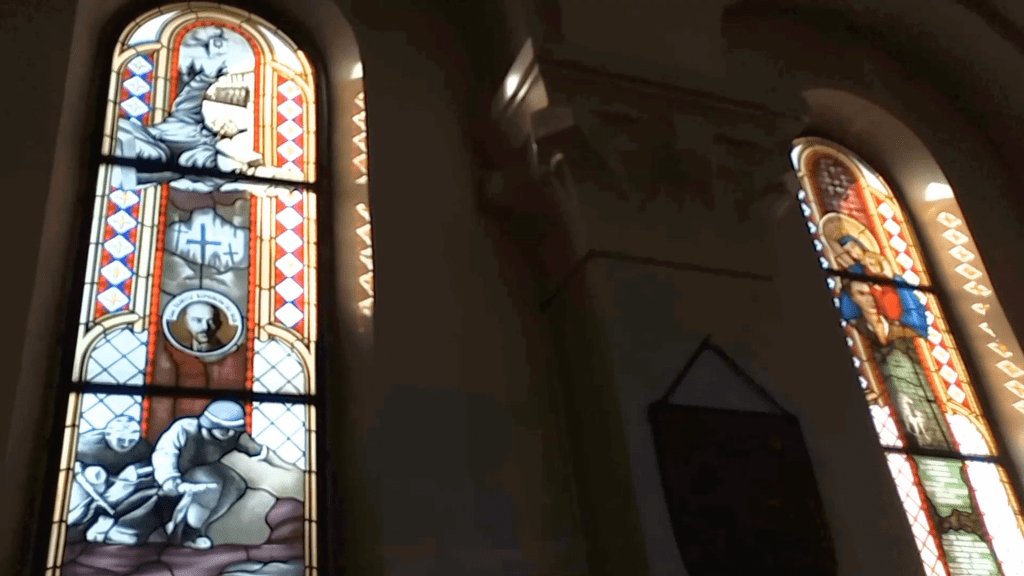

In the next world war the church suffered significant damage, with the original stained glass windows completely destroyed during the Warsaw Uprising. Thankfully, the church was fully restored after the war, with the original stained glass artist returning to create new windows.

Featuring the typical array of Christ and the Saints, these new panels also now paid tribute to the war with images of soldiers and tanks.

Despite how spooky some of the art is, the church feels like a sanctuary of peace within the bustling Ochota neighborhood.

After I said my prayers I hopped my tram, whisking across the city with comfort and ease. The first tramlines in Warsaw were built in 1866, with the early trams being horse-drawn carriages.

Today 25 lines cover 90 miles of the city with service.

I got off at Warszawa Gdańska train station, and caught a train north to Olsztyn, a lovely little city with a charming old town tucked in the trees.

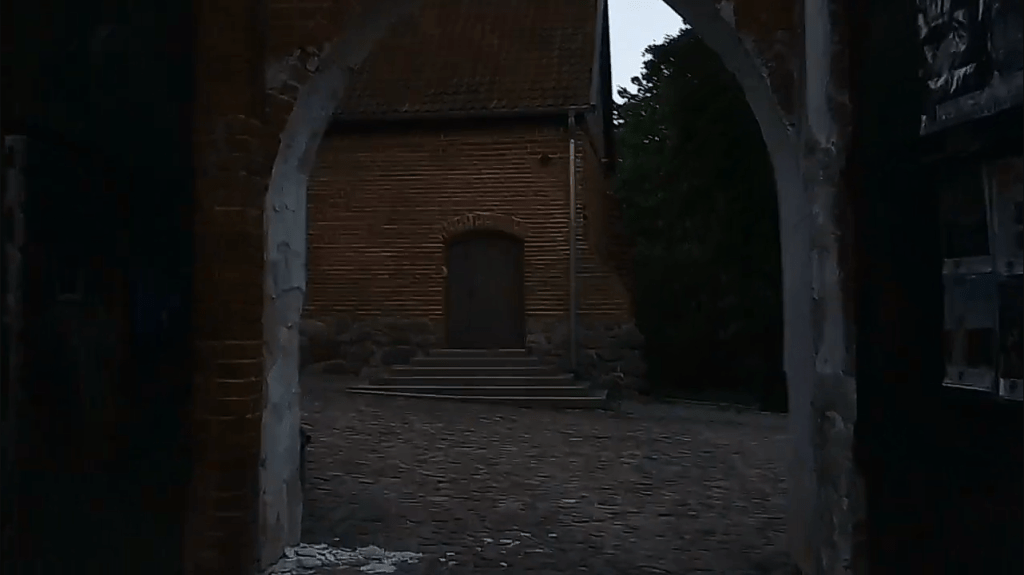

Founded in the mid 1300s by the Teutonic Knights, it had centuries of Polish and Germanic history existing together since its founding, only losing most of the latter population at the end of the second world war.

The Łyna River winds through much of the city, serving as the southern and western borders of the medieval town, and once acted as a moat for the fortified town.

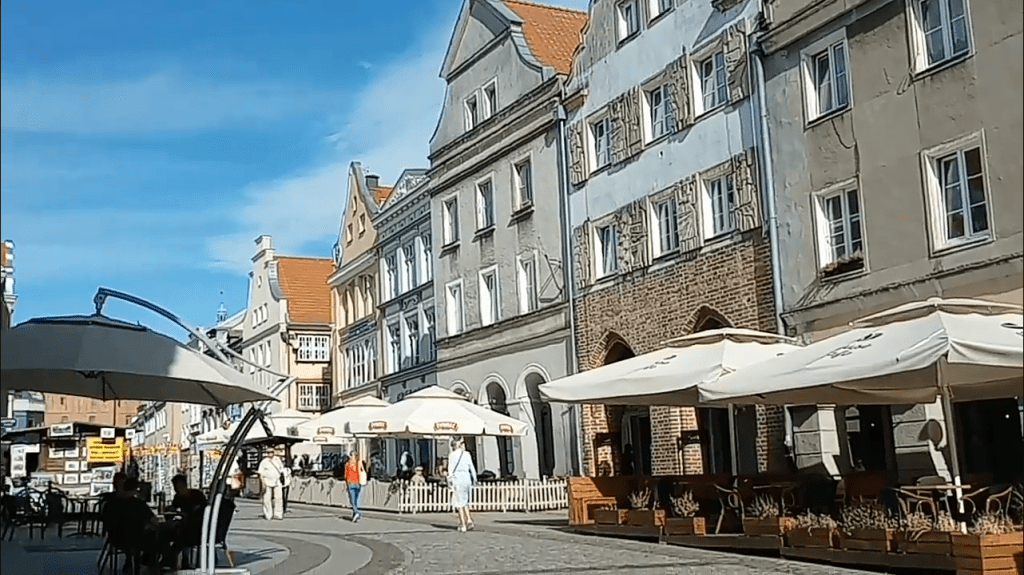

The centuries of styles present in old Olsztyn make for a delightful blend, with rows of baroque townhouses giving the town square a rather fairytale-esque allure. As an American used to car culture, I can’t help but feel we lost something when we abandoned this urban design for vehicular throughways.

The whole pace of life feels as if it slows down despite the bustle of human activity, and personal space becomes more fluid and relaxed when the plaza holds us all safely together in that common humanity.

I booked a room adjacent to the one remaining medieval gate at the Hotel Wysoka Brama, which was the perfect location at the edge of the old town.

My room was a great value for $19 a night, even if the shared bathroom shade was totally busted in the men’s showers, with the window looking directly out on the plaza below…

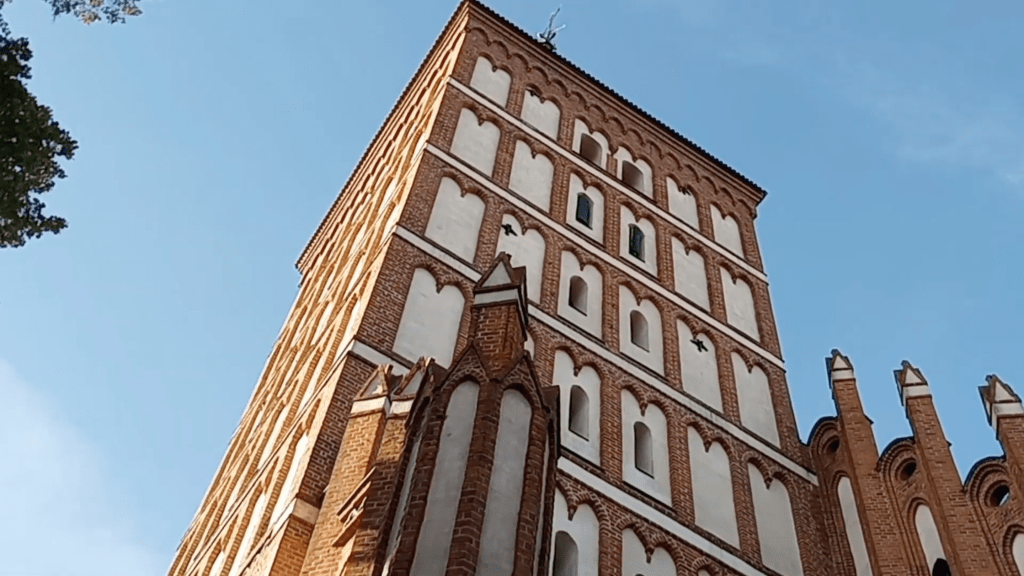

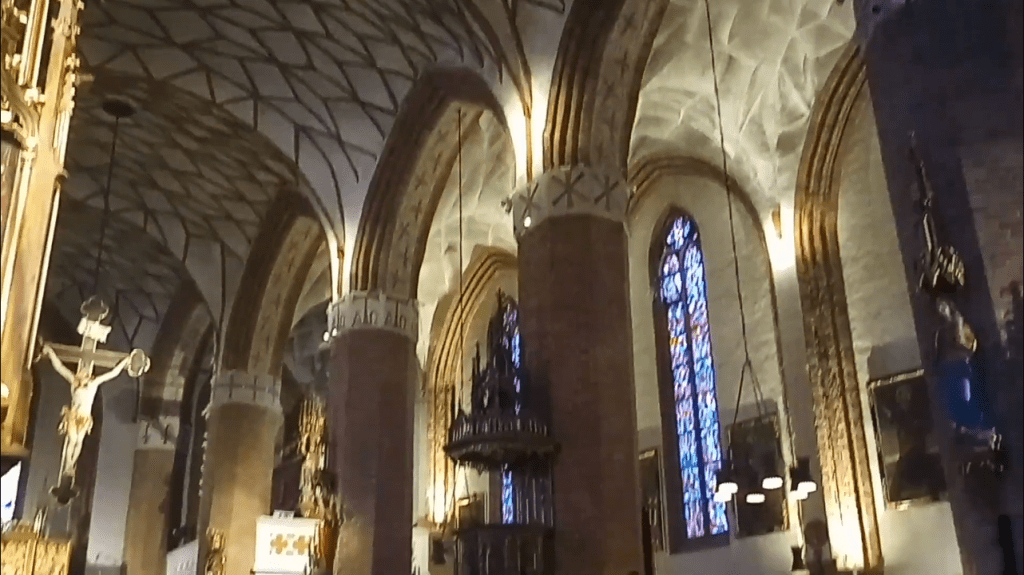

The late-medieval Basilica of Saint James is a particularly remarkable piece of old Olsztyn. It would take 2 centuries for it to reach its full towering splendor from the time its construction began in the mid 14th century, initially completed with only the bottom half of the tower built by 1410. It wasn’t until 1562 that major work to finish the tower would resume, reaching its final height in 1596.

The church suffered significant damage in the early 19th century, when the French army used it as a prison for Russian and Prussian soldiers during the Napoleonic Wars. Confined over a brutally cold winter, the prisoners, as many as 1500 by some accounts, burned much of the original medieval woodwork for warmth.

The fires caused further damage to the structure itself, severe enough that the vault collapsed 12 years later. Subsequently a decade was spent on renovation, conservation and restoration, in the process doing much to return to the original gothic character of the basilica that had been altered over the centuries.

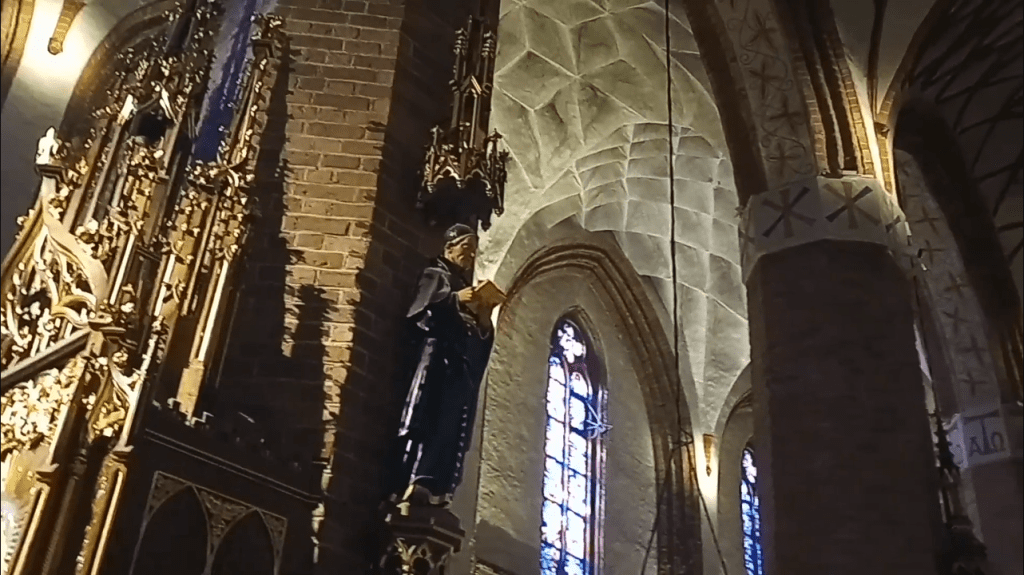

Today the combination of rib vaults and diamond vaults stunningly attest to the ingenuity of gothic architecture. The latter in particular represents Central Europe’s unique and vital contribution to keep the gothic style evolving while Poland was being influenced by the creative energy of the Renaissance.

The history of Catholicism in the Warmia region dates back to the 13th century, when the Teutonic Knights were sent to Christianise the land’s pagan tribes. By the time Olsztyn’s cathedral was constructed, the Teutonic Order and the Kingdom of Poland’s often contentious relationship had come to a head, erupting into warfare at the Battle of Grunwald in 1410, where the Order suffered a decisive defeat. Their military forces now broken, they retreated to their stronghold in Malbork.

For the next century, most conflict between the two powers in the Warmia region would be over church matters, but, in 1521, the Order laid siege to the town. Polish forces successfully withstood the assault, forcing the Teutonic Knights to ask for an armistice. The end of the Order’s power has a lightly ironic twist, as its grand master, who now paid tribute to the king of Poland, had become a convert to Lutheranism.

Poland itself would largely resist the Protestant Reformation, remaining steadfast and devoutly Catholic to this day, although in the last decade the percentage of the population identifying as such has declined from nearly 90% of the country to somewhere closer to 75% today. It will be interesting to see what happens in the next decade.

Pope John Paul II conducted a service in Olsztyn Cathedral in 1991 during his pilgrimage, and in 2004 he granted it the title of minor basilica. The first and so far only Polish Pope, his time as the leader of the faith from 1978 until his death in 2005 was a peak, pivotal time for Catholic Poland. The entire country took a kind of patriotic pride in him that would help the nation ride the storm of the Soviet Union’s demise.

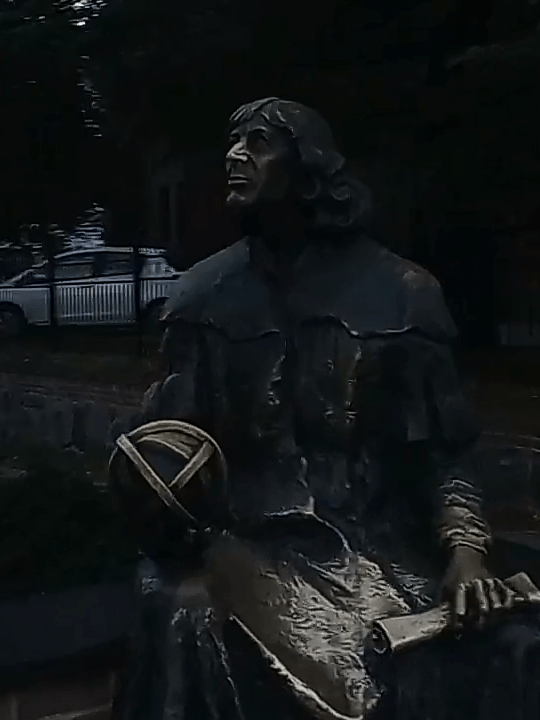

Olsztyn itself was one of the creative hubs of the Renaissance in Poland. Nicolaus Copernicus, a true Renaissance man if ever there was one, resided there for a time. Working out some astronomical calculations on the walls of the 14th century castle, he also organized its defense against the Teutonic Knights. Today his statue keeps watch across the bridge into town.

I’d hoped to have time to visit the castle museum, but it proved to be too tight on just a single overnight visit. Instead I settled for a morning stroll around the perimeter, admiring its lofty exterior that included nooks and crannies for the pigeons to perch and observe.

A single day in Olsztyn really wasn’t enough to taste all that it had to offer, but it was delicious enough to make it part of my future plans. In truth, the city wasn’t yet done with me, or perhaps I wasn’t done with it, as I would have to double back the next day to retrieve my tote bag I’d left behind at the local diner.

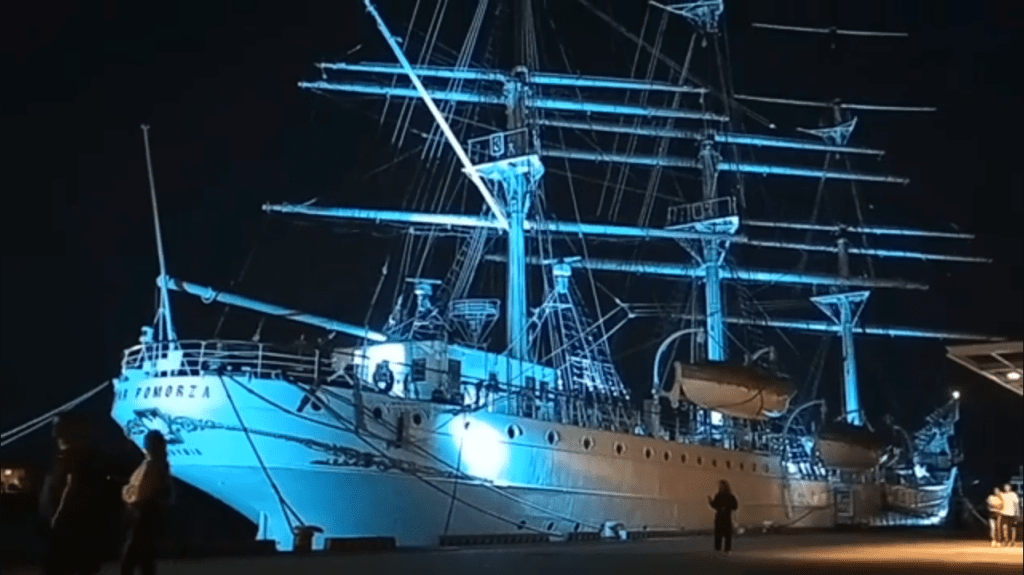

From Olsztyn I headed north to the Baltic coast to Gdynia. One of Poland’s youngest cities, it was built as a port hub for the newly re-independent Polish nation in the 1920s. I arrived on a perfect late summer day to my deluxe room in the trees and walked down through a sandy path at the end of the road that spit me out right across the street from the Baltic Sea coast.

Gdynia’s growth from a small fishing village to the port hub of Poland’s Baltic coast came as a result of the first world war. Before then, the entire region had been part of the German Empire. After the war, the region was integrated into the new Polish state, with the notable exception of Gdansk, then called Danzig. That city now became entirely independent of any nation.

Poland found the lack of control over this international port to be too much of an impediment to its own economic needs, and so, in the process of asserting its own re-emergent national identity, Gdynia was born.

Today, with the smaller but bustling tourist town of Sopot connecting them, the area is known as the Tri-city. A great place to enjoy the beach on an early Autumn day.

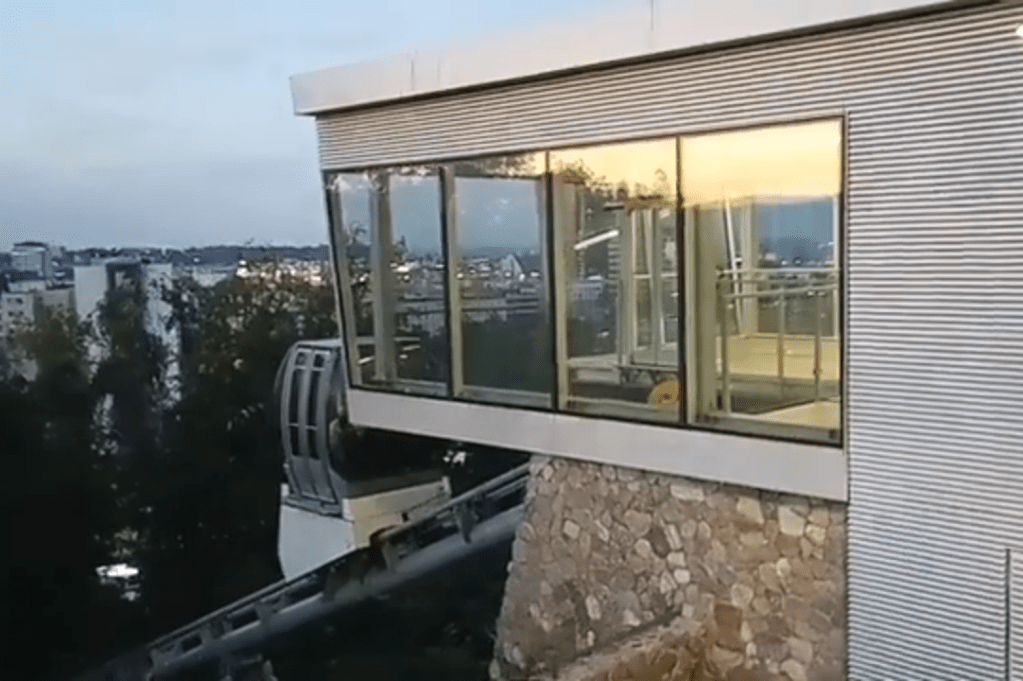

I had hoped to make it to Sopot and hike some of the bluffs above the coast, but the only bluffs I managed to make it to were those above Gdynia’s coastal promenade on Mt. Kamienna.

52 meters above sea level, I’m not exactly sure how many stairs that translates to, but it’s more than a few.

The villas that greet you at the top of the stairs have a delightful coastal flair to them, feeling almost more Mediterranean than anything.

A large steel cross, built in 1993, overlooks the Port of Gdynia. It is the third cross to occupy the spot. The first wooden cross, erected in the 1930s, was destroyed by the occupying German forces in World War 2. A second wooden cross, erected after the war, was later removed by the communist rulers in the 1960s.

A free funicular tram goes up and down from the top of the hill and into the city, where there was all sorts of summer fun still going on day and night.

The city of Gdynia was constructed a few years after the seaport, really beginning to grow and take shape after 1928. Within a decade it would be home to over 120,000 people, with a development plan that expected that population to double.

In the period that followed the end of the second world war, the city received a large population influx from former residents of devastated Warsaw and elsewhere throughout the country, as well as Poles from the eastern cities like Lwow and Wilno that were now part of the region annexed by the Soviet Union. This redrawing of Poland’s borders remains in effect to this day, with modern Lviv a part of Ukraine and Vilnius in Lithuania.

Despite the tragedy of such seemingly arbitrary upheaval, these new arrivals probably couldn’t have found themselves in a better place. The city has been consistently ranked as one of the best places to live in Poland. Despite only having a century of charm to fall back on, it’s not hard to see why.

To be continued…

Previously:

Leave a comment