Late in the summer of 2023 I made my 2nd journey to Poland, arriving in Warsaw September 18th on a beautiful sunny day. My first journey had been a whirlwind 9 day adventure almost a year prior; this time I’d squeezed out a full two weeks to revisit some of my favorite spots and explore other areas yet to be seen, timing my visit with the end of summer for optimal adventure weather.

As a major modern metropolis of Europe, Warsaw has a robust public transit system, better than most American cities. Navigating the bus system is relatively painless, as long as the ticket kiosks are working. “Welcome to Poland. It doesn’t work”, was the greeting on my first trip. I’ve never encountered any kind of fare enforcement in my bus or tram travels. If you can’t get a ticket for some reason my advice is to not sweat it. The main challenge with the airport buses is just finding a space to squeeze into for the ride.

My bus took me directly to Artur Zawisza square, where I stayed for two days at the AB Hostel. Zawisza was a Polish revolutionary who participated in the November Uprising of 1830 against the occupying Russian forces, with Russia having annexed a large portion of the country in the prior century. After the failed rebellion he fled to France, but in 1833 decided to return. He visited his family, wrote his will, was captured by the Russians, and was executed by hanging in the square that now bears his name.

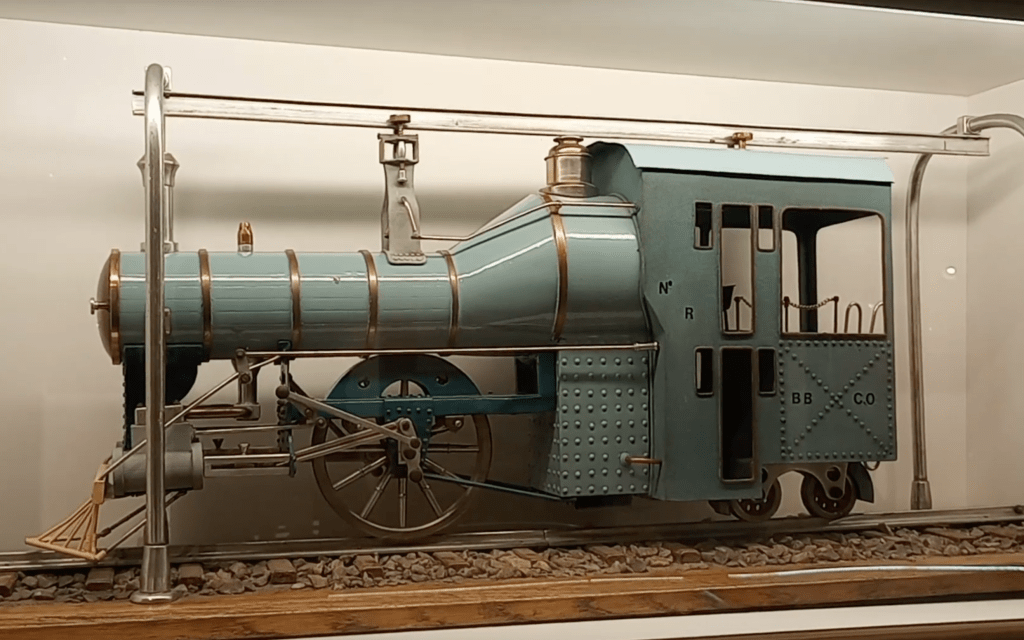

I was just a block away from the Warsaw Railway Museum and, in a further stroke of luck, had arrived on the day of its free weekly entry. The inside is largely given over to a display of intricate scale models, providing a thorough look at the evolution of railroading.

Have you ever seen a bicycle steam engine? Apparently such a train ran in New York City on a 2 mile route to Coney Island with a double-decker passenger car behind it.

The old train station that houses the museum was built at the end of World War 2 at the only depot that survived war. It operated as Warsaw’s main passenger station until the central station was built in the 1970s.

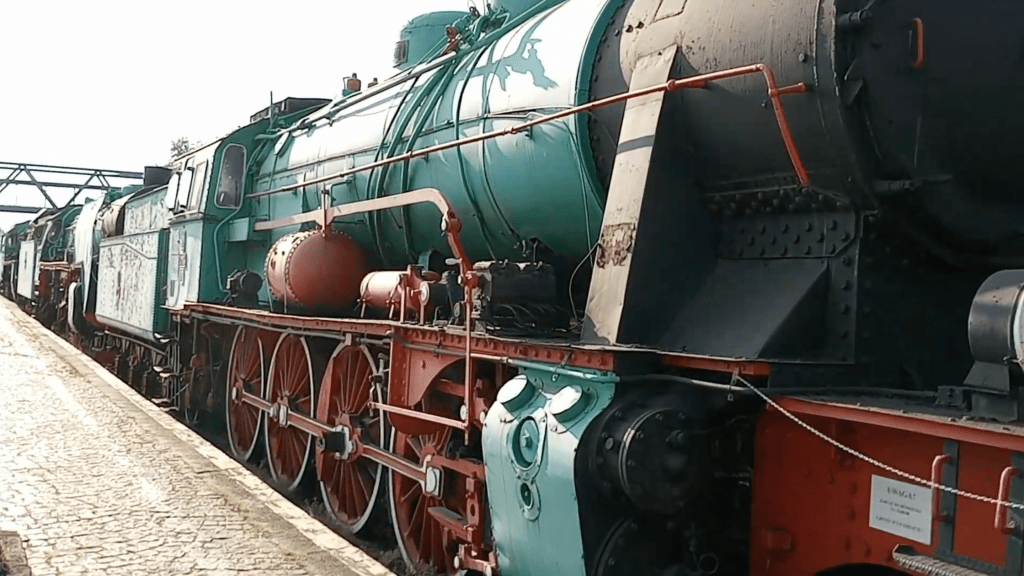

As compelling as the models are, it’s the “rolling stock” that makes the museum really special, that is to say, the full sized specimens on display. From impressively armored gun cars to the infamous “cattle cars” used for human transport by Nazi Germany, the history of the war comes through in Poland’s story no matter which angle you tell it from.

Not all of the stock is in pristine shape, but there are some steam engines that look like they haven’t aged a day in over a century, thanks to major maintenance and restoration efforts.

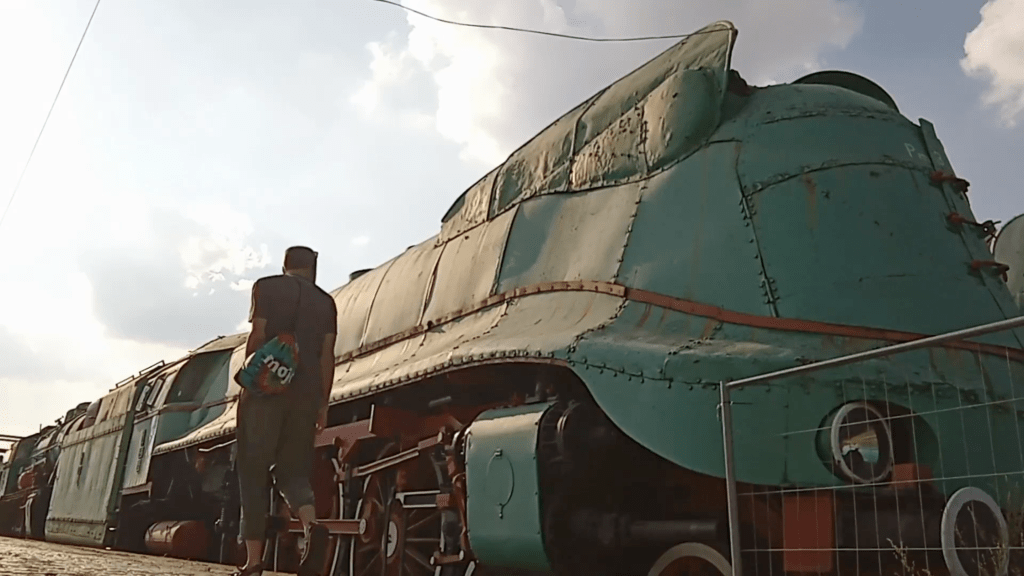

Prior to my visit I’d seen a picture of the big green art-deco streamlined steam-engine that lives there and fallen madly in love, so it was a delight to visit it in person. Looking slightly worse for wear but still the star off the show, she’s a big beautiful grasshopper and a sight to behold.

Locomotives such as this represent the final evolution of the steam engine, attempting to apply new theories of aerodynamics to make the engines go faster, better. Truth be told, it was more of a stop-gap retrofit than a truly revolutionary design. The fact that this German-built model has survived with its shell intact makes it a rare specimen; most engines of this type later found themselves stripped of their distinctive streamlining, revealing a typical looking steam engine beneath.

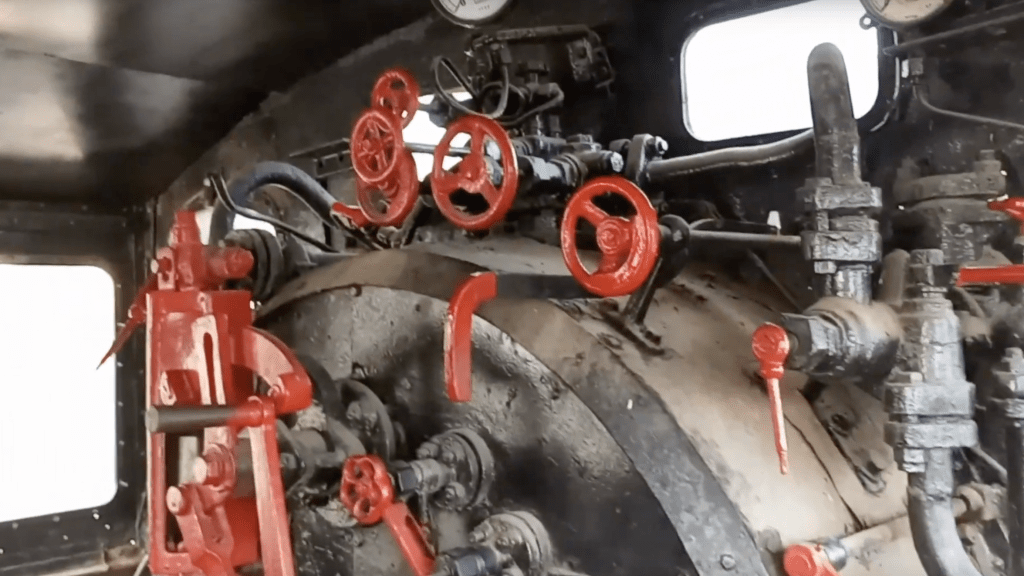

Looking inside some of these old beasts, it’s hard to imagine making heads or tails of all the valves and levers, but I guess that’s the kind of thing you commit to memory when becoming a train engineer. I just know I’d feel nervous without a cheat sheet.

Steam engines remained in usage in Poland through the 1970s, but by the end of the decade they’d been replaced by diesel locomotives. These days, the showcase engines only make an occasional appearance for special events, like a steam engine run to Hel a few years ago. The Hel peninsula, that is, back when you could still catch bus number 666 out there, before an offended conservative group put an end to that irreverent tradition.

A few of the trains have open cabs that you can climb up into and imagine yourself as the engineer. Gaze upon the gleaming red controls and think of all the ways things could go horribly wrong should these controls fail. You’re playing with elemental forces here under serious pressure. Like feeding the fire of a volcano and effectively harnessing its explosive power without actually, you know, exploding. It’s gotta be a delicate balance.

For those wishing to see the Casey Jones-esque tragic horrors of how badly things can go wrong, there is a “railway disasters of Poland” photographic exhibit in an old passenger car. The sight of a blown boiler is the kind of thing to give H.R. Giger nightmares.

At least if something like a blizzard comes, there’s a 45 year old turbine-powered snowplow train to clear the track. Keep on pushing, little buddy. The horrors persist, but so do you.

The next day turned to drizzle and then dumped buckets of rain, but this fit perfectly with my plans to visit the National Museum in Warsaw and soak up some phenomenal artwork on its free Tuesday entry.

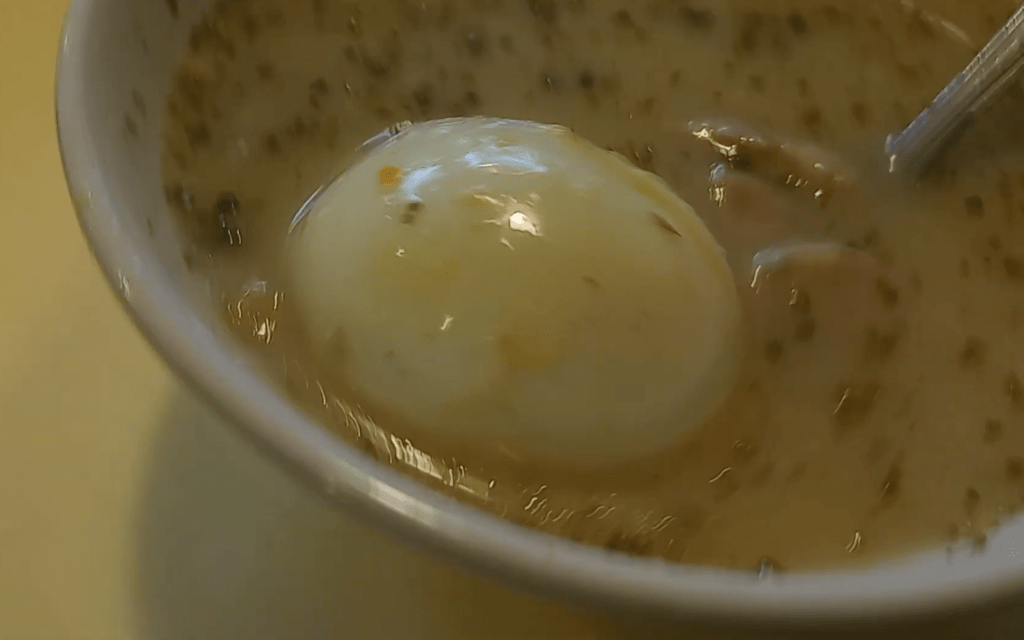

First I went to Bar Mleczny Lindleya and tried a bowl of zurek, a traditional Polish soup made from fermented rye, which really hit the spot, and gave me the perfect fuel for my museum fest.

“Old Cook With a Spit” by Italian painter Giovanni Francesco Briglia is a great example of the kind of delights that await you when you step inside the museum. That said, it was often the lesser known Polish artists that really blew me away, with the era of Polish realism capturing light and atmosphere in truly remarkable ways, but more importantly capturing a sense of the life and spirit of the land. They often feel like a portal back in time, giving a vital, precious glimpse towards the Poland my ancestors once inhabited.

This glimpse is often as tragic as it is idyllic, with much of Poland’s history consumed by warfare. Huge canvases capture both the brutal clash of famous battles and of the massive displacement and impoverishment of the poor people who found their lives and lands destroyed.

It was in the time of the Napoleonic wars that my Prussian ancestors had decided they’d finally had enough of the instability, moving east to Ukraine. In the century of art that followed their departure, death and the toil of living take on ominous, mythic, even absurd proportions. Poland’s most famous composer Friederic Chopin is sculpted as if all the wailing spirits of the land haunt his compositions. Another striking sculpture is simply titled “pain”.

For a land that has suffered so much over the course of its history, it seems fitting for Catholicism to make its roots deep and lasting in Poland. The medieval art section of the museum is entirely dominated by the religious iconography of the faith, with Christ’s pain and death always front and center.

That’s not to say the whole gospel story of his life doesn’t get equal attention, but that image of Christ on the cross will always be Catholicism’s central iconic image, with the Holy Mother as a close second.

The childhood of Jesus and his cousin John is fascinating to see depicted throughout the ages. A common approach is to make the children look older than their years, with young John often appearing as a tiny adult rather than a child. Jesus’s baby face features also appear much older. This was meant to show the full depth of adult wisdom the two already possessed.

As art evolved during the Renaissance, the depictions become less stylized and more relatable, if still loaded with iconic symbolism. Italian master Sandro Botticelli’s Holy Family portrait is particularly striking, the figures popping forth with an almost uncanny presence. The painting that really hit me hardest was by Flemish artist Abraham Janssens, with the grief worn like a raw wound on the faces of Jesus’ family as they prepare his body for the tomb.

Meanwhile, the defiantly secular Palace of Culture and Science stands as Warsaw’s most iconic piece of architecture. Soviet Russia’s gift to Poland, semi-affectionately called “Stalin’s Erection”, it was the first modern skyscraper built in the country.

At the time of its construction, many found its ornate but brutalist style distasteful. Some still do. One thing’s for sure, Warsaw wouldn’t feel the same without it. To me it’s a fascinating example of the atheistic Soviet attempt to elevate the human spirit to the heights of religious iconography, which is especially interesting to witness in such a devoutly Catholic country.

The Palace marks the place where post-war Warsaw began to define itself as something distinctly new, and the skyscrapers that have followed have continued that transformation, to the point where Stalin’s great modernist monument looks like the remnant of a bygone era. At any rate, it remains an impressive structure, and it gives you one heck of a good view of the city. In fact, it’s often been said it gives you the city’s best views… because it’s not in them.

Now Warsaw is vying to be the skyscraper capital of central Europe. It currently features 32 high-rises on its skyline, and as the city itself seems to be on the rise, expect more to follow.

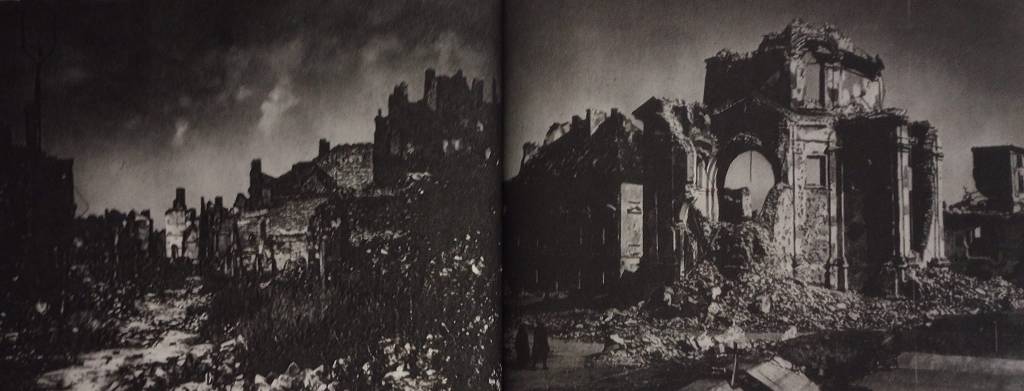

As for the prior history of Warsaw, it’s impossible not to get a strange surrealistic feeling from the city, as if it’s both older and younger than it looks. Well, that’s because it is. You see, despite the fascinating mixture of centuries of architectural styles, nearly 90% of the city is less than a century old.

With its existence stretching back to the 13th century, it’s difficult to reconcile the fact that hardly any of the original buildings remained intact after the 2nd world war. The retreating Nazi occupiers deliberately made sure of that.

Looking out from the viewpoints on the Palace’s upper floor, you see history that was literally pulled from the rubble. The rebirth of Warsaw was emblematic of the spirit of Poland, perhaps even essential to that spirit’s survival.

That, and also ice cream. You’re more likely to find an ice cream shop than a coffee shop in Poland, which isn’t to say that good coffee is hard to find, just that ice cream is everywhere.

After the war a new Polish government emerged in alliance with Soviet Russia. The Palace of Culture and Science is perhaps the one monument to that government’s existence that is guaranteed to endure.

It doesn’t take much effort to see the old time religious spirit has still hung steadfast and strong, reclaimed from the devastation of the war to rise above the reborn city.

The first time I visited Warsaw, I was unaware of how truly devastating the war had been to Poland’s capital. Today, reconstructed from every piece of rubble that could be salvaged, the old city stands proudly once again as a faithful tribute to itself.

Known as the Phoenix City, it seems intent on lasting another 700 years with the life it currently possesses. Like the skyline, Warsaw’s spirit continues to rise from its tragic past, growing and evolving in ways its founders never could have imagined, yet remaining familiar enough in its old haunts that an ancient ghost could still feel at home.

Leave a comment