November 11th: Warsaw

My transit timing meant I really didn’t manage to catch any of the parades or other festivities related to Independence Day. When I got to Warsaw there were folks with flags on the streets, but otherwise, by that point, it just seemed like another day in a dynamic metropolis.

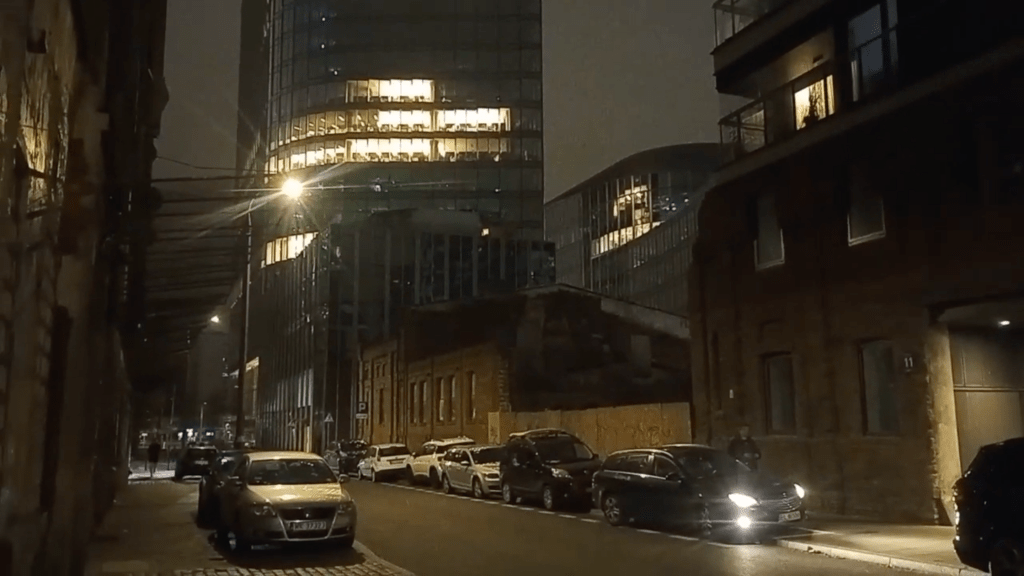

My journey towards the hostel really emphasized the modern heart of the city, impressing me with its towering sprawl. Somehow I’d never seen it like this before. It always felt like little pockets of towers, but from this approach they lined the promenade. The perfect reacquainting glimpse of Warsaw rising as I prepared to dive deeper into its devastating and compelling history…

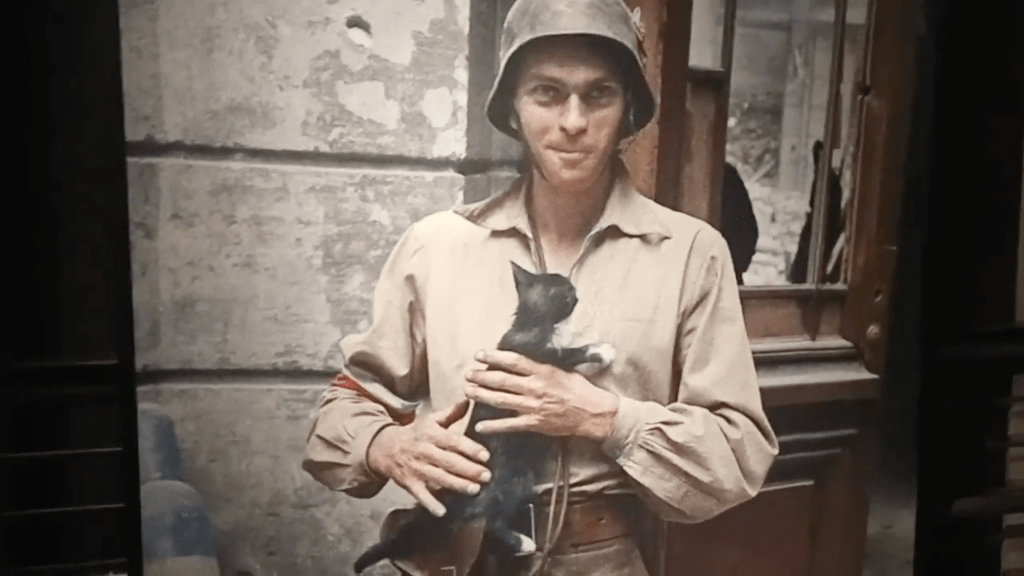

Just over 100 years ago the Warsaw Uprising unsuccessfully tried to overthrow the Nazi occupation, thinking help was on the way that would guarantee their victory. They had been building a resistance since the city was first occupied. For months they had been spurred on by Allied propaganda to rise up. The Polish Home Army, assessing their chances, seeing the weakened German forces, believed that Allied forces would support their uprising and together they would triumph against the Nazi oppressors.

Unfortunately the Soviet Red Army had different plans. They set up across the river and ensured that was the only part of the city that survived, content to hold their ground and wait for the Nazi occupiers to retreat. The Polish Home Army sensed that they would have to take their chances fighting the Germans, hopefully achieving political leverage in achieving their own liberation, rather than letting the Soviets lead the charge and become liberating conquerors.

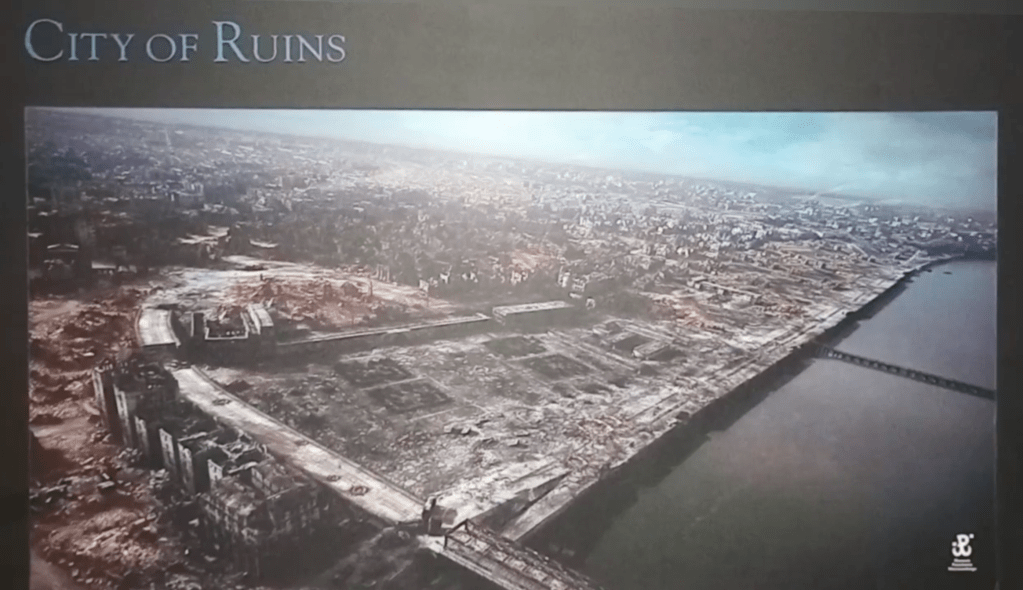

After two solid months of intense fighting between the Poles and the Nazis, with the Soviets idly observing the entire duration, the uprising was finally crushed. The entire city was then reduced to ashes and rubble by Nazis forces before they finally retreated, leaving the Soviets free to move in and liberate the ruins.

There seem to be a number of reasons for Soviets not intervening and supporting the uprising. Many historians believe that Stalin wanted the uprising to fail to weaken the non-communist Polish resistance, making the USSR’s annexation of Poland significantly easier to accomplish. Given Stalin’s track record, this seems highly likely, especially given the persecution of members of the Polish Home Army following the war.

Needless to say, the Poles were deeply wounded by this lack of support, a support they’d been made to feel was imminent. One can’t help but wonder how much of that wounded resentment, 35 years later, was behind the Solidarnosc movement in Gdansk, the movement which would ultimately prove fatal for Soviet authorities to resist.

Figures of how many people ultimately survived the occupation and destruction of Warsaw are hard to come by. In a city of 1.5 million people, the highest estimate is around 300,000. Many historians put the number much, much lower, but there was so much displacement during the war it is hard to say.

80 years later Warsaw rises up to the sky like a modern metropolis. Despite Nazi attempts to crush the city and destroy the Warsovian spirit, it not only survived but it thrives today as one of the greatest cities in the world. Part of that survival began in tribute to the old city, but its modern face has proven just as impressive. It took me a few trips to truly appreciate that current pace of development. The first time especially, I didn’t fully understand the depths of ruination it had to rise from.

Today, I find the entire sprawl of the city enthralling, an interwoven dynamic of new that’s old and old that’s new, with practically nothing truly historical remaining, just meticulously reconstructed rubble built on a heart that somehow never quit beating, a spirit that never was crushed. The heart beat on, the spirit rose, and Warsaw rose anew with it. Today, it rises still. I look forward to seeing what new heights await it…

The next morning a stroll across Krasiński Garden took me past the Monument to the Battle Monte Casino. Standing 12 metres tall and weighing 220 tons, the monument depicts a headless and battle scarred Nike, the Greek goddess of victory, in tribute to one of the key battles of the Italian Campaign in 1944. Nearby a smaller plaque is dedicated to the people of Iran for taking in 120,000 Polish refugees during the war, a fact I never would have guessed.

On the other side of the park stands Rzeczypospolitej Palace. Completed in 1695, it was 85% destroyed by the end of World War 2. Sometime when I make it inside I’ll give it a more detailed investigation.

On the other side of the park I ran into the west end of Poland’s Supreme Court building, which is a monument in itself, built in the late 90s. The columns that surround it are covered in legal maxims in Latin and Polish.

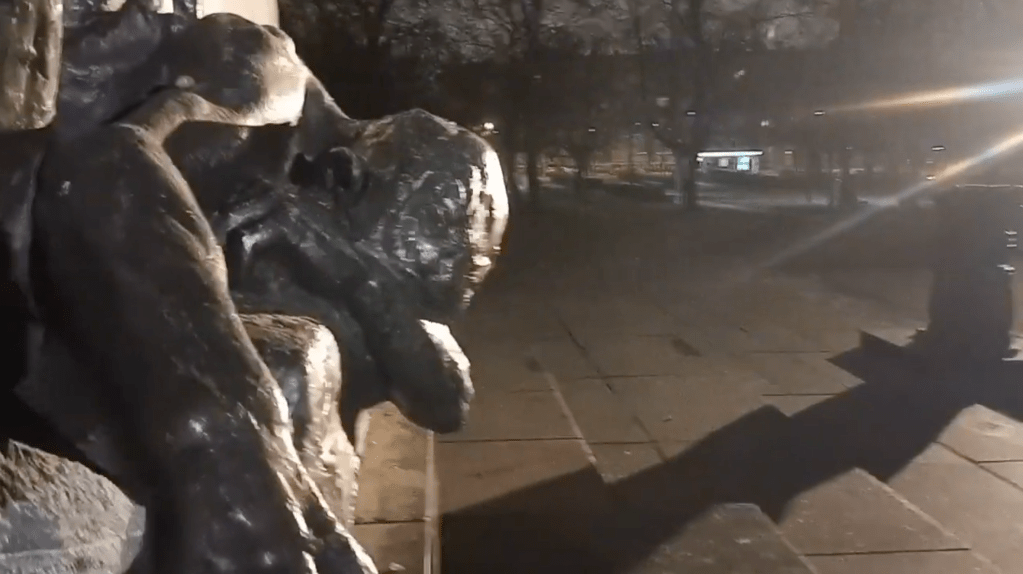

The Warsaw Rising monument, so memorably captured in “A Real Pain”, is on the other side of the building. I would have liked to revisit it, but at this point time was running short and I was intent on maximizing my free museum opportunities, so I hustled on past Kransinski square.

Maria Skłodowska-Curie Museum

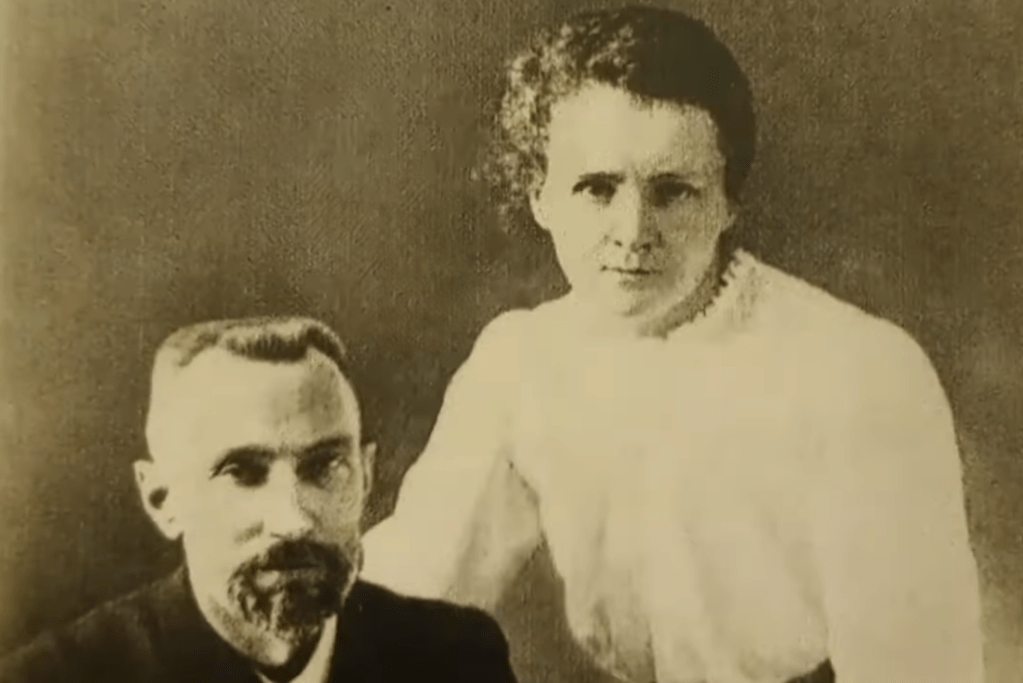

Pierre and Marie Curie were the ultimate scientific power-couple, sharing a Nobel prize for discovering radiation. Unfortunately Pierre’s head full of ideas didn’t perceive the carriage that was barreling down the lane as he stepped out and was swept under its wheels and instantly killed. A perfect life together cut tragically short.

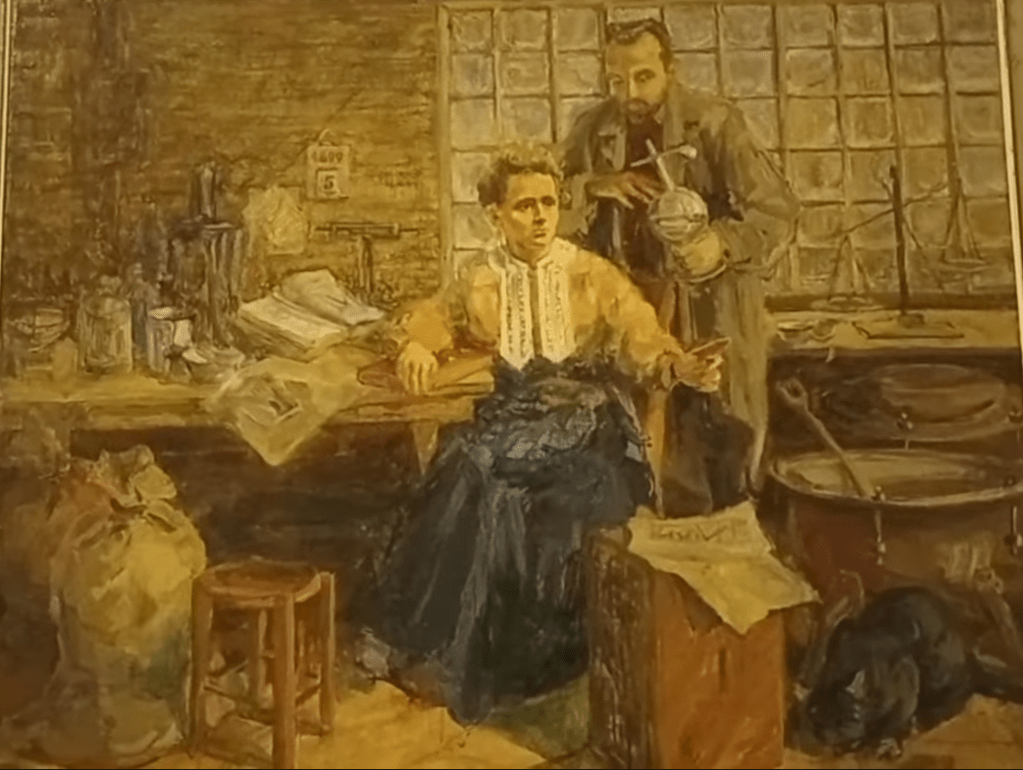

There’s been much speculation that Pierre’s death may have in some way been the result of radioactive poisoning contributing to his demise. I too couldn’t help but wonder, especially after seeing the incredibly primitive equipment that they were discovering modern science with… it’s hard to even wrap my mind around any of it. This is the road that led to the atomic bomb, and it barely seems any more sophisticated than the methods the alchemists used searching for the Philosopher’s Stone. Is that what the Curies ultimately discovered? In many ways it was more like opening Pandora’s Box.

They’d met together in Paris, after Maria Skłodowska had been rejected by the Academy of Science in Krakow. It wasn’t love at first sight, but gradually a partnership based on deep mutual respect finally blossomed into romance. The realization of their potential as life partners was expressed to Marie by Pierre as a partnership of dreams:

“It would be a beautiful thing, a thing I dare not hope if we could spend our life near each other, hypnotized by our dreams: your patriotic dream, our humanitarian dream, and our scientific dream.”

Marie was finally won over to the idea, but insisted on practicality. If it was to be a life partnership based in pursuit of science, then make the wedding dress something that can double as proper lab attire:

“I have no dress except the one I wear every day. If you are going to be kind enough to give me one, please let it be practical and dark so that I can put it on afterwards to go to the laboratory.”

Their marriage would produce 2 daughters, along with a Nobel prize for discovering radiation, a prize that Pierre had to insist Marie be awarded with him.

Marie carried on after Pierre’s death and won a second Nobel prize in recognition of her work in radioactivity. She would soon apply those principles directly to the battlefield medical units of World War One with mobile x-ray machines, nicknamed “Petite Curies”, often traveling to hospitals in the company of her daughter.

She died at the age of 66, her anemic body unable to produce enough blood cells to stay alive, a result of decades of prolonged exposure to radioactivity. Both her and Pierre have been re-entombed together in France’s national mausoleum, the Pantheon. Their coffins are lined with lead, with Marie’s body’s radioactive half-life extending another 1500 years or so.

St. Hyacinth’s Church was just down the street from the museum, the perfect place for a sanctuary to recenter in before heading through the meticulously reconstructed old-town. Named after one of Poland’s own saints, the exclamation “St. Hyacinth with his dumplings!” refers to legends of his miraculous restoration of crops and pierogi-manifesting abilities. Krakow holds its annual pierogi festival on his feast day, the 17th of August.

Completed in 1639, the church would serve as a field hospital for the Warsaw Uprising forces, becoming a frequent bombing target by the Nazis. Only fragments of the interior were able to be preserved after the destruction of the city, but they offer a tantalizing glimpse of the details that once adorned the space, now set off against the stark white of the rest of the reconstructed space.

From there it wasn’t far to the little fortress of the Warsaw Barbican, which serves as the gateway to the historic city center. Oftentimes when the weather is nice you’ll find local artists selling their paintings within the passage.

I have yet to make it inside the rebuilt Royal Castle. I was under the impression that entrance was free for the month of November, but it turns out that’s only partially true? It’s a little confusing. Some access is free but much is not.

The thing that makes Warsaw so much fun to revisit is the fact that you’ll never see all it has to offer in one journey. I’m glad I skipped the castle and assorted places this time around, especially since I really needed a whole afternoon at the National Museum… and I still haven’t caught up with that famous painting of Stańczyk the distraught jester. Turns out he was loaned out to the Louvre for an exhibition called “Figures of the Fool”. Next time, joker.

Józef Chełmoński at National Museum of Warsaw

I first saw Józef Chełmoński’s work 2 years ago visiting Warsaw’s National Museum. One of the leading proponents of the realist style, his paintings have a light and liveliness that makes you feel as if you’ve stepped into a time machine. Last year I was lucky enough to arrive in Warsaw when the museum was hosting a full retrospective of his work.

Chełmoński’s travels took him throughout the borderlands of Eastern Poland, into regions now part of Ukraine, Moldova and Belarus, but it wasn’t until he briefly settled in Paris during the pivotal era where impressionism emerged that his work became truly renowned. I suspect his influence upon that scene has yet to be fully appreciated, with his use of light and shadow producing breathtaking results.

Returning to Poland after visiting Vienna and Venice, he eventually ended up settling in the village of Kuklówka Zarzeczna, 40 kilometers southwest of Warsaw, where he would remain settled until his death, running his own farm. Many of his most beloved works were painted during this time, with his love for the rural countryside and the lives of those who lived there captured to stunning effect.

A subject of the Russian Empire his entire life, if he’d managed to live 5 years longer he would have witnessed the rebirth of the independent Polish nation. 110 years after his death he is recognized as one of the greatest Polish Patriotic Painters. Seeing these monumental pieces in person makes it easy to understand why.

Polin: Museum of the History of Polish Jews

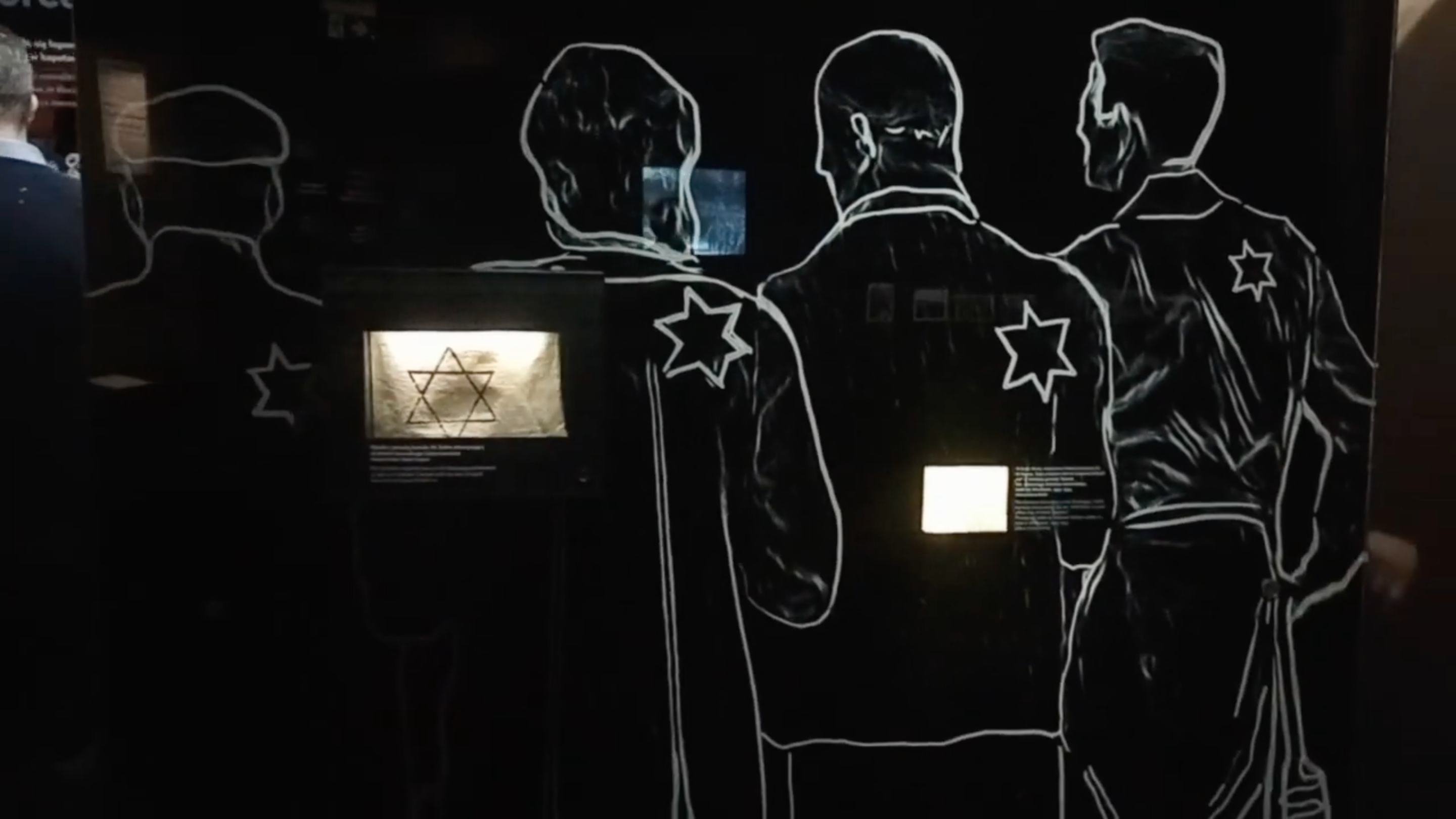

1,000 years of history, consolidated to 600 ghettos, 90% slaughtered, and never safe. Poland and the history of European Jews were intrinsically tied together. Both grew in tandem, and both were almost annihilated. The culture that existed in that exchange will never be restored now.

In the 16th and 17th century 80% of the world’s Jews resided in Poland. The partitions of Poland in the 18th century resulted in many of the rights of Jews that had been guaranteed for centuries to evaporate, leading many to emigrate westward to Germany and France, and later to America. Still, when Poland re-emerged after the first World War, it contained 3.3 million Jewish citizens, 30% of the world’s Jewish population. By the end of the Holocaust, the Nazi regime would annihilate 3 million Polish Jews, and another 3 million throughout Europe, with the Soviet Union suffering the second highest losses with a million murdered.

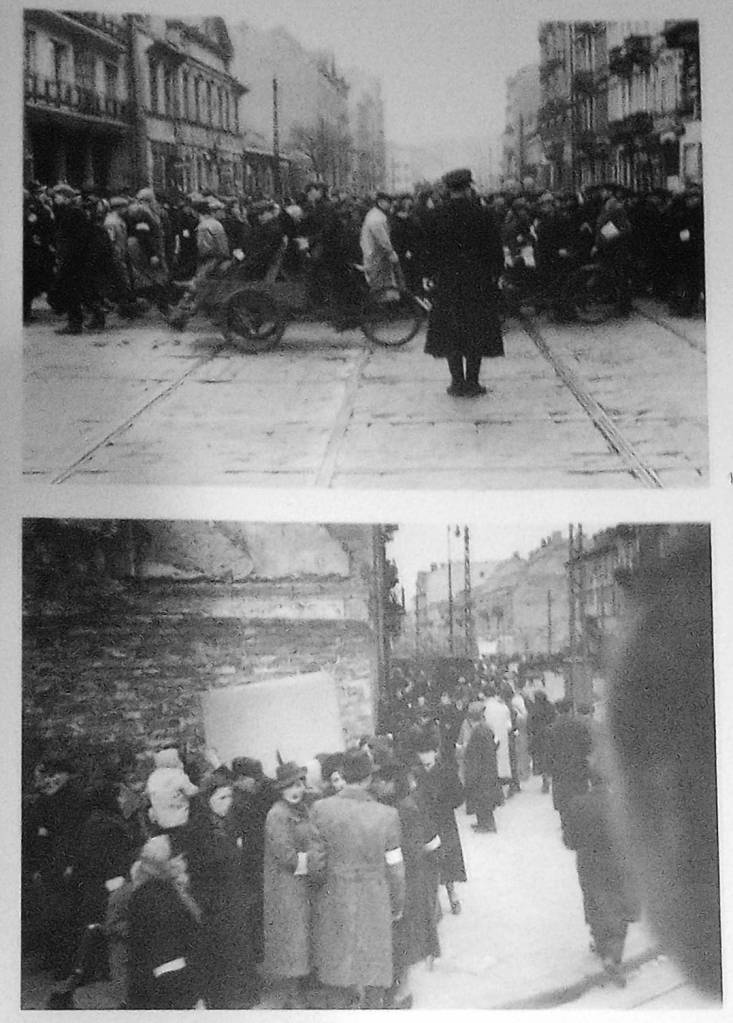

Warsaw’s Jewish ghetto was the largest in the country. At it’s peak there were more than 460,000 people crammed into the 1.3 square miles within its walls. To put that into perspective, Manhattan has just under 100,000 people in the same amount of space.

As I wandered through the empty voids of Muranow where the ghetto once stood, I felt as if I saw a blur of all those people surrounding me. Perhaps it was just my imagination running away with me, but it was a vivid, shocking moment. It was only later that I saw photos of that sea of people, just as I’d seen their spectral presence surround me.

The first mass deportation from Warsaw’s ghetto was a “resettlement to the east.” To the Treblinka camp.

The highest estimate of those who ultimately survived the Warsaw ghetto was 20,000, although many historians believe it was only a few thousand.

They say Muranow is a deeply haunted neighborhood today. Unlike so much of historic Warsaw, nothing was reconstructed where the Jewish ghetto stood. The entire street grid is different. The cynic in me can’t help but wonder if this was done to dissuade any survivors who might have sought to return. It hasn’t kept the ghosts out.

A few weeks after returning to the states late last year I found myself in an open and vulnerable emotional state suddenly finding myself attempting to give voice to those ghosts in some kind of balladic form. I still haven’t come up with a melody to it, but it only seems fair to give the “ghosts” the last word, even if it’s just me haunting myself…

Muranow

I.

They built the townhouses

on your burial mounds

They dug up your ashes

from out of the grounds

Ground your bones into mortar

to plaster the walls

It’s little surprise

that you’ve haunted us all

When nothing remained

they laid down a new grid

If the pattern is altered

then the ghosts will stay hid

No old streets to wander

no old haunts to roam

but the ghosts of the ghetto

call the townhouses home

They died in the cellars

They died in the streets

They died on their hands

and they died on their feet

They died in the city

and in the camps, too

And their ghosts keep returning

to haunt me and you

II.

A sea of humanity

withered away

These streets

at a glance seem barren today

But when you glimpse in the shadows

the sea will appear

The waves of their spirits

still hauntingly near

When at last liquidated

the ghetto was razed

The ones that remained

called the rubble their graves

But they weren’t consecrated

they weren’t honored at all

They were mixed in the mortar

that plastered the walls

You ghosts of the ghetto

what have you to say

Why is it you come here

to haunt us this day

May we not rest in peace

in this house we call home

We’ve our lives left to live

please leave us alone

III.

If peace is the question

then peace is the cause

If our presence unnerves you

then it should give you pause

Would a spirit of peace

be haunting as well

Would you seek first

the Kingdom

Or run

straight into Hell

If the suffering continues

the ghost sea will grow

Until suffering spirits

is all that you’ll know

Your own seas will wither

your rivers run dry

And the whole world

could end

But the suffering

won’t die

May a spirit of peace

come to haunt you today

To shock and unnerve you

to follow the way

Where the Holy Ghost Guides you

through the shadow of death

There’ll be peace in the valley

when you draw your last breath

Leave a comment