November 6th: Bydgoszcz

Bydgoszcz is tucked in where the Brda River forks off the Vistula. The little river and the old city wind together so dynamically, you can easily lose track of what side you’re on after a few bridges.

The town square was once centrally dominated by a memorial statue dedicated to the Poles who were executed in Bydgoszcz during Nazi occupation; that monument now stands a bit less drastic feeling in a corner, still a somber reminder of the suffering and persecution that swept over this land.

The history of violence here turns out to be rather complicated upon further investigation. The varied perspectives and historical accountings remind me of the film “Rashomon,” where none of the witnesses’ testimonies to a crime align with the others’. It’s only in the last 20 years that both sides have agreed that there were Germanic residents there that directly collaborated with the Nazis. The subject of how many Germanic citizens were killed in the subsequent days by angry Poles remains a messy one, with Nazis seizing on the incident for propaganda purposes during the war, calling it “Bloody Sunday”. Even at the lower end of the estimates the whole incident is pretty awful, with a population that once lived in harmony fractured in paranoia and quickly turned to enemies. It’s easy to forget how long Germanic settlers had been part of Poland’s landscape. In many places the two cultures had overlapped since medieval times.

Outside of town there is a place known as the “Valley of Death” where in the following two months 1,200-1,400 Poles and Jews were rounded up and slaughtered and dumped in a mass grave. Like much of the early Nazi victims, these were mostly the intellectual leaders of Polish society – destruction of higher thought within a culture was always the first step of the genocidal path. The same kind of violent purge was carried out early in the occupation of my old family haunt of Pabianice.

I didn’t have the gumption to get out to this darker historic spot. I was too busy dwelling on the current darkness in the world’s history. There was only so much heavy lifting to be done in this journey, and there was already much more back in Warsaw I knew was awaiting me. This whole river stretch wasn’t meant to carry such weight; it’s only in reflection now that it even emerges.

With that in mind, the winding river and the open air felt freeing after the slightly claustrophobic confines of old Toruń. Bydgoszcz also has that funky old-milltown feel that speaks in weird poetry to me. Knowing as you watch a cascading current rush down a channel that a waterwheel once stood there to harness that energy, driving an engine of the city’s industry, always sends me deep into reverie.

Meanwhile, the medieval cathedral along the river rewards the senses with a stunning feast of blue, indigo and blood-orange arches and expanses framing centuries old iconography and gilded finery. In the end it’s those colors that stick with you, making it one of Poland’s must-see cathedrals. My first peek inside was when the lights were off after dark, with just the altar illuminated. That’s the perfect introduction, but I’m glad I came back to see it fully lit up the next day.

There’s an incredible feeling in these old churches, with their centuries of veneration, a feeling of safety and sanctuary, of peace descending on the wings of a dove from the great vaulted heights. Just old enough to feel like the “Haunts of Ancient Peace” that Van Morrison sang of. Some of it resides in the brilliant architecture itself, with even early 20th century neo-gothic churches possessing that divine symmetry of two wings pointed towards the elevated cross.

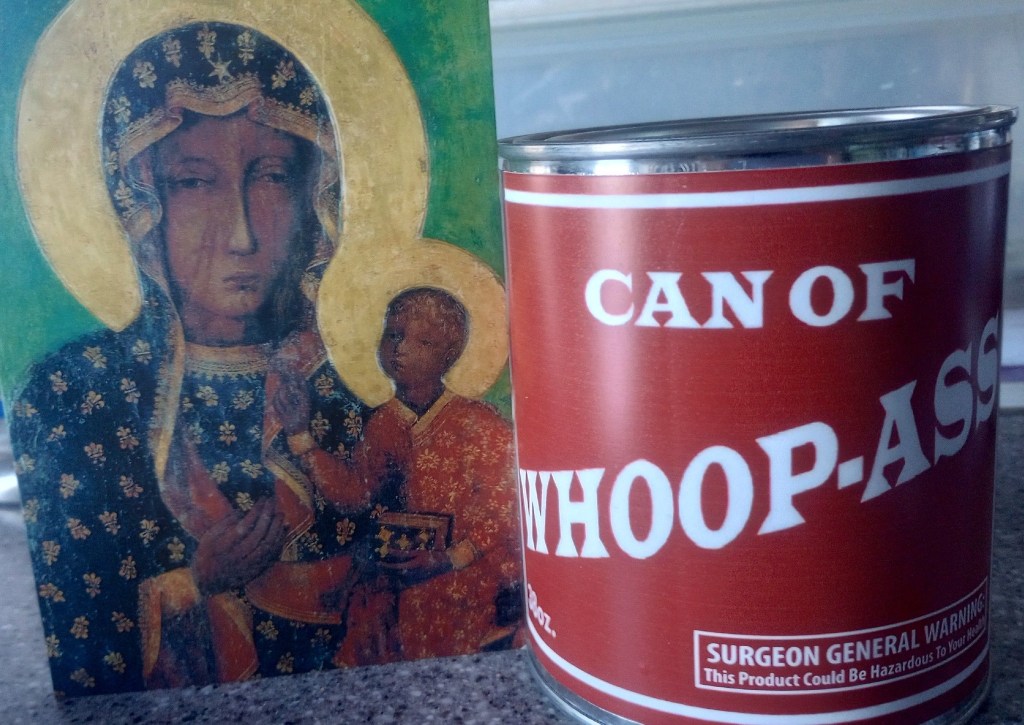

The Holy Mother was always my most direct and resonant pathway to the old haunts of Catholicism. Coupled with the Sacred Heart, she remains my touchstone throughout the journey, ever since my first Polish pilgrimage brought me to the entrance of Jasna Gora Monastery in Czestochowa and the blessed greeting it bestowed upon me.

It was in Bydgoszcz that I finally acquired my own reproduction of Jasna Gora’s Black Madonna, Poland’s unique homeland holy matriarch, in the form of a $3 glossy card. She is a stunner, a bold, stern Mother. Two slashes across her cheek are said to be inflicted by the sword of a frustrated 15th century raider who tried to make off with the icon but whose horses refused to move. The Mother has always been very insistent about remaining there. It’s said that before she was inflicted a third blow, the swordsman was struck down and writhed in agony until dead. This is a Mother you don’t want to mess with. Perhaps the next blow was intended for the beloved child. Regardless, the message was clear, that she would not suffer grievous harm and would remain strong through all suffering to protect her children.

The dominant imagery of Christ upon the cross is Catholicism’s most disturbing motif to someone like me raised in the modern “born-again” Christian tradition. To be fair, there is something to be said for making suffering a universal truth by showing a God that experiences all the suffering, endlessly. It seems like kind of a raw deal though. I was always taught the importance of the crucifixion was the subsequent resurrection. I was also taught to equate a lot of magical thinking with the Christian faith, a faith that, because Jesus died for our sins, meant that we are to be free from suffering entirely, when we are walking in faith.

Many stumbles later I’ve come to lean more towards some kind of Zen-Catholic approach to reconcile any kind of faith in the divine – attempting to forge the optimal path through a passionate life, and the inevitable suffering that comes with such a path, so that this life’s greatest lessons might best be learned.

Anyhow… where did I end up going in Bydgoszcz? It started feeling kind of Dr. Seussical sometimes. I got invited to a strip club again, but I was wise to that scam, thanks to the Death Stairs Community.

I checked the local movie times and discovered that Porco Rosso was playing. The Studio Ghibli animated feature has a pig for a pilot in a whimsical plot with sky pirates. I think it’s eventually revealed why the pilot is a pig, but it’s been so long since I’ve seen it in English I can’t remember; being a Japanese movie in Poland, the subtitles were Polish. I sat too close to the screen and passed out for half the movie. It was exactly what I needed.

I actually went to the wrong theater first. There were 2 different multiplex locations playing the series of Ghibli rereleases, but the first had it playing 2 hours later. Luckily the buses run regularly and it was a quick hop between locations.

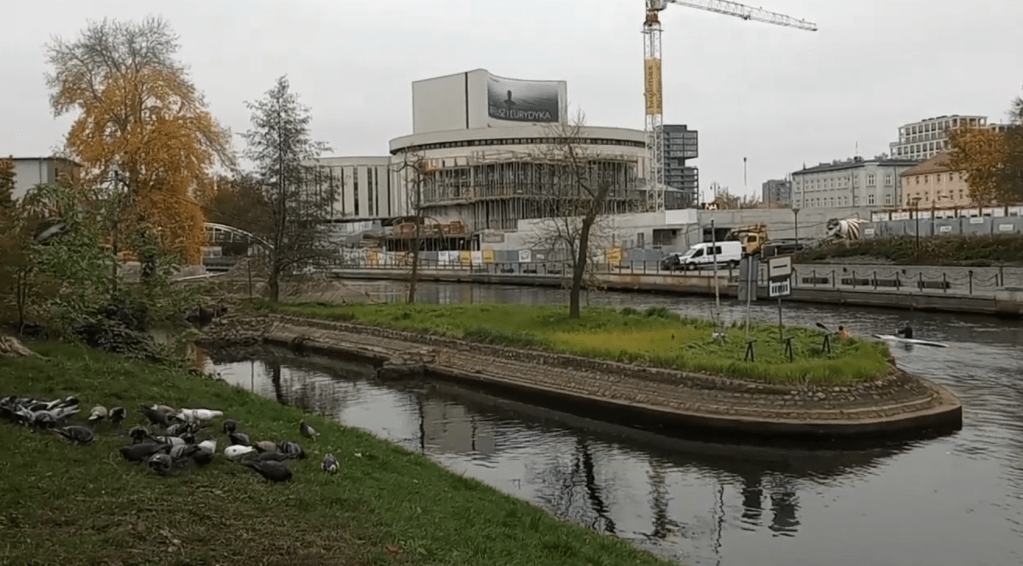

Elsewhere along the river, the Opera Nova looks to be expanding a whole new circular wing. The original opera hall, built in 1956, has been a cultural landmark in the region ever since. This new expansion will feature its very own little cinema, amongst other things. It will increase the capacity of a pretty robust looking artistic institution, with seemingly endless operatic performances in the works.

As far as instrumental composers go, Piotr Moss seems to be the main man in town. Active since the 80s, his work has moved from defiantly modernist to more accessible romantic territory recently – cinematically evocative and perfect for my purposes. His star adorns the walk of fame in front of the hotel I stayed in.

One of the things I always enjoy seeing in Polish river towns is the life that congregates around and on those rivers. Fishermen on the shores, kayakers gliding swiftly by, bicycles cruising along the waterfront, pigeons surveying the whole scene. Healthy and alive, classically urban but not a congested, suffocating metropolis.

Breathing that river air feels refreshing. In a Ghibli film there would probably be something to say about its spirit being a healing entity – both in bringing such energy to the inhabitants there, but also being itself in a state of healing after being at the mercy of centuries of industrial pollution. Namaste, River Brda.

November 8th: Grudziądz

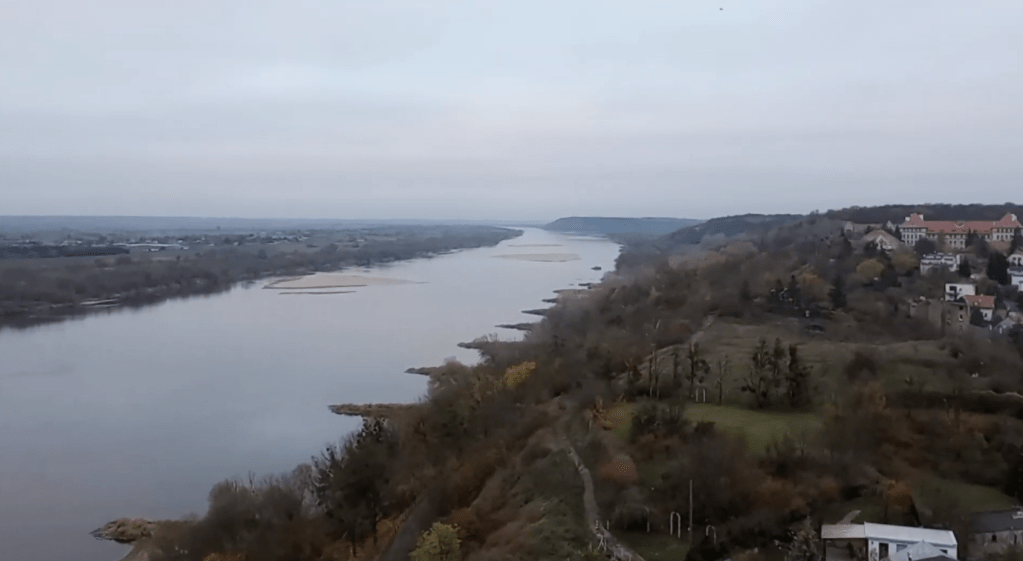

Grudziądz is back on the main stretch of the Vistula, around the corner to the east of where the Brda branches off. The first time I saw a picture of its medieval fortress exterior I was deeply, madly in love, and knew I must see it in person. We are fortunate it still exists, considering that 60% of the city was destroyed by the end of the second World War. Enough damage was done to the old structures that it took 20 years of rebuilding efforts following the war. Unfortunately the old castle tower was destroyed in that final battle, but lucky for us it was totally rebuilt in 2006, providing a brilliant panoramic view of the city.

Nearly a millennium ago the settlement was established as a defensive stronghold by Poland’s first king, Bolesław I the Brave, with the fortress and tower built to ward off attacks by Baltic Prussians.

Once again, like old Toruń, we find the history of this town is as much Germanic as it is Polish, with the Teutonic Order being responsible for re-fortifying the settlement in the “count it off” year of 1234. Shortly later they began building the castle, and the settlement soon evolved into a proper township, under the rule of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights.

The Catholic St. Nicholas’s Church was constructed towards the end of that century, and it’s one of the first things that greets you when you walk up the stairs that penetrate through the middle of the old fortified walls from the riverside.

The oldest parts of that church actually predate the current fortifications. Not merely constructed for defensive purposes, they were also granaries that were central to the growing town’s economy. Built along the older defensive walls, wooden gutters ran down from them to the riverside port, allowing grain to be directly loaded onto ships. The first several granaries were constructed in the middle of the 1300s; by the early 1500s there were over a dozen. The tiny windows that line the walls were built for archers to be able to rain arrows down on invading forces.

Like many Polish towns, Grudziądz became fed up with the oppressive rule of the Teutonic Order, and along with Toruń and 14 other townships founded the Prussian Confederation to oppose them. The citizens of Grudziądz forced the Teutonic Knights to hand over the castle at the beginning of the Polish-Teutonic War and, with the peace that followed Polish victory 13 years later, Grudziądz was finally re-incorporated to Poland.

Nicolaus Copernicus made his way to the town in 1522, where he delivered his Treatise on Money. Not merely content to ponder the circular orbit of the planets, he was equally concerned with the circulation of money, postulating the classic theory that “bad money drives out good.” He also formulated one of the earliest versions of the quantity theory of money, recognizing that an excess amount of money in circulation could drive up the price of goods. Pretty much all of the classical economic theories that followed built directly off his work.

Grudziądz experienced its first major wave of destruction in the mid-17th century, when the “Swedish Deluge” swept over Poland, and the town was captured and occupied by Swedish forces. 4 years later, when they were finally driven out, much of the town was destroyed by fire during their retreat.

With the collapse of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth roughly a century later, and its partition between the Kingdom of Prussia, the Austrian Monarchy, and the Russian Empire, Grudziądz once again found itself under Germanic control.

It was the king of Prussia at the turn of the century that decreed the old Teutonic castle be torn down and a new fortress be built in town, leaving only the old tower standing. The new fortress was completed just in time to successfully defend the town against Napoleon’s forces.

These forces, it must be said, were supported by many Poles throughout the land wishing for the country to regain its independence, something Napoleon had promised if they would join him. When he was ultimately defeated, it was a victory for Germanic forces, but a much more complicated and conflicted outcome for the Polish people. It would ultimately take over a century, and another horrific world-wide conflict, for Poland to finally become an independent nation again at the end of the first world war.

In the meantime, Grudziądz became the site of a military prison for Polish activists, with hard labor, beatings and malnutrition par for the course. King Frederick, who had little love for the Polish people, began flooding the new Prussian lands with Germanic settlers, and passed sweeping Germanisation laws; the lands where Germans and Poles co-existed now became like apartheid states, with bans on the Polish language and religious practices going hand-in-hand with Germanic colonization.

Towards the end of the 19th century, Grudziądz (nee, Graudenz), was almost 60% Germanic. By 1910, 84% of the population of the town and 58% of the surrounding countryside was recorded as German. There is controversy surrounding these numbers, with some historians saying that anyone who registered as bi-lingual was considered German. Germanized, at any rate.

After WWI and the re-incorpation of Grudziądz to the reborn Polish State, its newly appointed Polish mayor, Józef Włodek, described the town as “modern but unfortunately completely German”. A new program of Polonization was implemented, and much of the Germanic population subsequently emigrated back to German territories. Those that remained were now the minority, and were treated with contempt and paranoia by the Poles, fearful of any re-Germanization attempts. As the Nazis rose to power in Germany this paranoia only grew, with the Germanic school in the town found to follow the party’s lead, causing much alarm and outrage. Later in 1933, two German craftsmen were killed by a Polish mob.

The worst fears of the Polish residents came to pass in 1939 with the beginning of the second world war. Following the Nazi invasion, 25 Polish citizens of the town – priests, teachers, and others of influence – were taken as hostages, threatened with execution if any harm came to the ethnic Germans from the city who had been detained by Polish forces during the invasion. Unfortunately it seems this was ultimately a false promise of safety, as even after the Germanic prisoners were released and the Polish hostages let go, they were shortly later rounded up again and shot by the Nazi authorities.

This was only the beginning of the horrors that followed, with mass executions taking place at nearby Księże Góry. Towards the end of the war Soviet forces would occupy the hill, shelling the city from the old fort at its peak. Unfortunately it took destroying over half the city to liberate it. The remaining German population fled or was expelled to Germany. Taking their place were Poles from places like Lwów (Lviv), which had been historically a Polish city but was now incorporated into Soviet Ukraine when the post-war borders were redrawn.

All this is to say that Poland has had an incredibly complicated history; it’s honestly remarkable that it even exists today.

As the sun rises over those big granary walls, the local fisherman start to arrive, launching their little boats from the riverside park. The industry that built up around the old town churns away. With that indomitable Polish spirit, Grudziądz just keeps on keeping on.

ICYMI:

Here’s the complete 2024 journey in one handy playlist:

Leave a comment